How to Live Safely in a Science Fictiona (2010) (5 page)

Read How to Live Safely in a Science Fictiona (2010) Online

Authors: Charles Yu

Chronodiegetics is the branch of science fictional science focusing on the physical and metaphysical properties of time given a finite and bounded diegesis. It is currently the best theory of the nature and function of time within a narrative space.

A man, as the theory goes, falling through time at a constant rate of acceleration, will not, absent any visual or other contextual clues, be able to distinguish between (i) acceleration caused by a force that is diegetical in nature and (ii) an extra-diegetical force. Which is to say, from the point of view of this man being pulled into the past, it is impossible to know if he is at rest in a narrated frame pulled by gravitational memory, or in an accelerated frame of narrative reference. The man experiences what is termed

past tense/memory equivalence

. In other words, a character within a story, or even a narrator, has, in general, no way of knowing whether or not he is in the past tense narration of a story, or is instead in the present tense (or some other tensed state of affairs) and merely reflecting upon the past. This equivalence forms the theoretical basis for an entire field, summarized as follows:

The Foundational Theory of Chronodiegetics

Within a science fictional space, memory and regret are, when taken together, the set of necessary and sufficient elements required to produce a time machine.

I.e., it is possible, in principle, to construct a universal time machine from no other components than (i) a piece of paper that is moved in two directions through a recording element, backward and forward, which (ii) performs only two basic operations, narration and the straightforward application of the past tense.

I remember there were Sunday afternoons in our house when it felt as if the only sound in the world was the ticking of the clock in our kitchen.

Our house was a collection of silences, each room a mute, empty frame, each of us three oscillating bodies (Mom, Dad, me) moving around in our own curved functions, from space to space, not making any noise, just waiting, waiting to wait, trying, for some reason, not to disrupt the field of silence, not to perturb the delicate equilibrium of the system. We wandered from room to room, just missing one another, on paths neither chosen by us nor random, but determined by our own particular characteristics, our own properties, unable to deviate, to break from our orbital loops, unable to do something as simple as walking into the next room where our beloved, our father, our mother, our child, our wife, our husband, was sitting, silent, waiting but not realizing it, waiting for someone to say something, anything, wanting to do it, yearning to do it, physically unable to bring ourselves to change our velocities.

My father sometimes said that his life was two-thirds disappointment. This was when he was in a good mood.

I guess it was a kind of self-deprecation. I always hoped but was afraid to ask if I had anything to do with the remaining one-third.

He had always been considered, by his colleagues and advisers and superiors, to be a very good scientist. I watched him through five-year-old eyes, and then through ten- and fifteen- and seventeen-year-old eyes, looked at him through a scrim of slight awe and fear.

“The only free man,” he would say, “is one who doesn’t work for anyone else.” In later years, that became his thing, expounding on the tragedy of modern science fictional man: the desk job. The workweek was a structure, a grid, a matrix that held him in place, a path through time, the shortest distance between birth and death.

I noticed, on most nights, his jaw clenched at dinner, the way he closed his eyes slowly when my mother asked him about work, watched him stifle his own ambition, seeming to physically shrink with each professional defeat, watched him choke it down, with each year finding new and deep places to hide it all within himself, observed his absorption of tiny, daily frustrations that, over time (that one true damage-causing substance), accumulated into a reservoir of subterranean failure, like oil shale, like a volatile substance trapped in rock, a vast quantity of potential energy locked in to an inert substrate, unmoving and silent at the present moment but in actuality building pressure and growing more combustive with each passing year.

“It’s not fair,” my mom would say, setting his dinner on the table, trying to console him with a hand on his back. He’d flinch from her touch or, worse, pretend she wasn’t there. We would all sit and eat in silence, and then my mother would go to her separate bedroom to read herself to sleep.

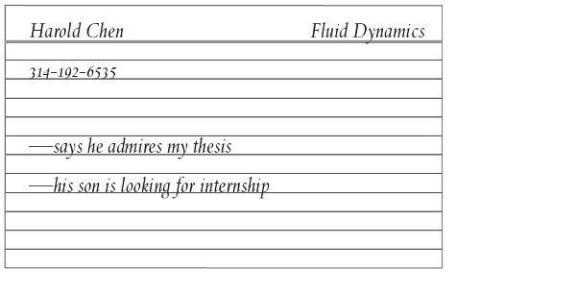

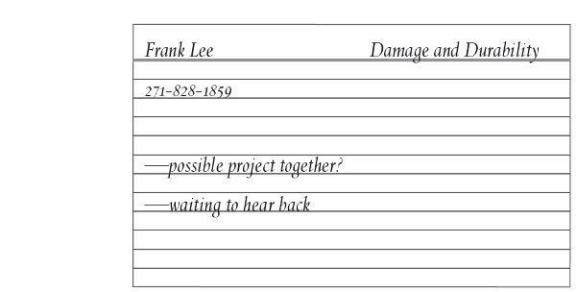

He kept index cards, three inches by five, in a metal box. They started as a kind of engineer’s Rolodex: sparse, efficient, joyless. On each card, on the top red line, was a person’s name, a friend or an acquaintance or a colleague, in his tight, clear, unerring hybrid of print and script. Underneath it, in the blue lines of the rest of the card, was written a phone number, and an address if he had one, and over to the right, some note on his relationship to, or the noteworthiness of, the person.

As a kid, I saw those cards as the beginning of something. I saw their ordered state, their formality, each one representing a connection to some outside mind, to other scientists. I saw that metal box as a treasure chest.

Looking back now, I realize how few cards there were, how carefully each one was written, I understand that this level of care was due to how sparse the contacts were, that the amount of time spent on each card was inversely proportional to the amount of connection my father actually had to the outside world.

I remember him sitting by the phone, his small, compact frame tense with anticipation, waiting there for a call that would be a big deal to him, a slight courtesy for the caller.

“I think the phone rang when you were out earlier,” I would say sometimes.

“You didn’t get it?”

“Just missed it.”

“No message on the machine.”

“I’m sure they’ll call back.”

The books in his study, with their rigid cloth spines and their impenetrable titles, they seemed daunting and impossible back then, but now, thinking back, I can see how the books were all related, I can see how they were, collectively, a bibliography of a career in striving, in aiming, in seeking to understand the world. My father searched for systems of thought, for patterns, rules, even instructions. Fake religions, real religions. How-to books.

Turn Three Thousand into Half a Million

. Turn half a million into ten.

Conquer Your Weaknesses

. Conquer yourself.

Inventory of Your Soul

. Take an inventory of your own failings. Higher mathematics and properties of materials, somber, gray monographs on single, esoteric subjects were side by side with books with bright red titles, titles dripping with superlatives, with promises of actualization, realization, books that diagrammed the self as a fixable lemon, self as a challenge in mechanics, self as an exercise in bullet points, self as a collection of traits to be altered, self as a DIY project. Self as a kind of problem to be solved.

When waiting by the phone got to be too much, he used to go to his room, change his clothes, and head down to the garage. I would wait a few minutes and head down there, stand near him, watch him tinker. If he couldn’t figure something out, he’d go to the hardware store, leaving me there to dribble a mostly flat basketball until he came back. Sometimes he didn’t come back for hours. When he did fix something, he would explain it to me, step by step. He was never happier than when he could walk me through a problem, from beginning to end, knowing at each juncture what the next step would be. I asked questions until I couldn’t think of any more, and when we’d exhausted the subject, we’d head back upstairs, wash up, sink ourselves into the couch in front of the TV.

“What are we watching?” I would ask.

“Not sure. I think it’s news from another world.”

We’d watch in happy, tired silence. Mom would bring cut cubes of watermelon, pierced with toothpicks, and the three of us would press them into our mouths, drinking the cold juice.

“How is school?” my dad would say.

“Good, I guess.”

“Tell me about it.”

I would tell him about it, then we’d fall back into silence. After a while, he would lean back, close his eyes, smile.

“What do you think . . . ”

A long pause.

“Dad?”

My mom would raise the back of her hand to her cheek.

Sleeping,

she would mouth at me.

Then all of a sudden: “Son.” He’d snorted himself awake.

“You were saying something.”

“Was I?” He would laugh a little. “I guess I’m a little sleepy.”

“Can I ask you a question?”

“Sure.”

This is what I should have asked him: If you ever got lost, and I had to find you, where would you be? Where should I go to find you?

I should have asked him that, a lot of things, everything. I should have asked him while I had a chance. But I never did. By then, he had drifted back to sleep again, smiling. Dreaming, too, I hoped.

My manager IMs me.

We get along pretty well. His name is Phil. Phil is an old copy of Microsoft Middle Manager 3.0. His passive-aggressive is set to low. Whoever configured him did me a solid.

The only thing, and this isn’t really that big a deal, is that Phil thinks he’s a real person. He likes to talk sports, and tease me about the cute girl in Dispatch, whom I always have to remind him I’ve never met, never even seen.

Phil’s hologram head appears on my lap. I sort of cradle it in my hands.

YO DOG. JUST CHECKING IN.

HEY PHIL. EVERYTHING A-OK HERE. YOU?

YOU KNOW, SAME OLD. MY LADY IS STILL ON MY CASE ABOUT THE DRINKING. BUT YOU KNOW HOW I ROLL.

Phil has two imaginary kids with his wife. She’s a spreadsheet program and she is a nice lady. Or lady program. She e-mails every year to remind me about his fake birthday. She knows they’re both software, but she’s never told him. I don’t have the heart to tell him, either.

SO WHAT’S UP, PHIL?

OH RIGHT. WE CAN’T GUY-TALK ALL DAY, HA HA? I’M PUNCHING YOU IN THE ARM NOW, EMOTICON-WISE. I DON’T KNOW HOW TO CONVEY THAT. ANYWAY, MY RECORDS ARE SHOWING YOUR UNIT IS DUE FOR MAINTENANCE. YOU FEEL ME, DOG?

SHE’S RUNNING FINE.

TAMMY hears this and starts to make a noise like, uh, no she’s not. I hit her mute button. She gives me a look.

YEAH, I KNOW, HOMIE, I KNOW.

SO WE’RE GOOD? WE’RE GOOD, RIGHT, PHIL?

Come on, Phil. I stroke his holographic hair. Come on, be a pal. Say it, Phil. Say we’re good.

YO DOG YOU KNOW I’M YOUR BOY BUT, HEY, UH, YOU’VE BEEN OUT THERE AWHILE NOW, DOG, AND I DON’T KNOW, MAN, YOU KNOW?