How to Raise the Perfect Dog (22 page)

Read How to Raise the Perfect Dog Online

Authors: Cesar Millan

Tags: #Dogs - Training, #Training, #Pets, #Human-animal communication, #Dogs - Care, #General, #Dogs - General, #health, #Behavior, #Dogs

Unfortunately, the family had had a bad experience with a Labrador puppy in the past, when the kids were toddlers. “The puppy was just really wild,” Adriana recounts. “She’d go after us all the time. To me it was too out of control. We’d leave her in the backyard, and we actually stopped going into the backyard; she ate the whole backyard up. Looking back now, with what Cesar has taught me, I’m sure that it could have been fixed. We were ignoring her a lot, we didn’t walk her, we didn’t exercise her. We didn’t balance her out at all. And I was thinking that she was aggressive, but really she was bored.”

I felt that my neighbors had earned a second chance, so when Blizzard, the yellow Lab we rescued for this book, turned four months old, I presented him to Adriana. Because I see so much of the family, Blizzard gets double benefits—the cozy comfort of being a family dog, as well as having access to living and playing among the pack at my house and at the center. Adriana and her family are fast learners, and they have all grown in their leadership skills by leaps and bounds, thanks to the challenges provided by a dog like Blizzard. But the dynamics of the Barnes family offer a great example of how different energies can affect the same dog.

SAME PUPPY, DIFFERENT WALKERS

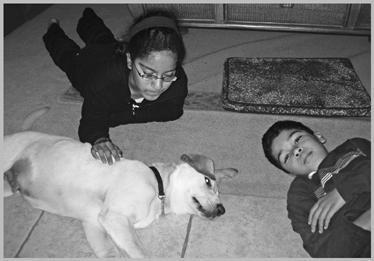

Fourteen-year-old Sabrina is a Dog Whisperer in training. She’s cool, confident, and exudes a calm-assertive energy—really impressive for a teenager. Her brother, Christian, however, is a more laid-back, quiet guy, and when Blizzard first arrived, he was much less self-assured with his new puppy. Blizzard picked up right away on Christian’s hesitation. Whereas Sabrina would walk Blizzard without any problem, with Christian, the energetic Labrador would pull ahead or to the side.

“Cesar says that Christian and Blizzard are both the same energy,” says their dad, Terry. “So when they’re both the same energy, he’s not going to listen to Christian. My boy, he’s so quiet and so timid, I think that’s one thing. Sabrina will get right on Blizzard if he pulls away, whereas Christian will be yelling, “Stop! Don’t!” Yelling at him in full sentences. Too much talk. Like Cesar says, ‘They don’t speak English; they don’t speak human.’”

Blizzard hanging out with Sabrina and Christian

Despite Christian’s lower energy level, when Blizzard would get worked up, Christian would become nervous and tense. “He’s only a puppy,” says Sabrina, knowingly. “He’s trying to figure out who to follow. He’s like a kid. And with Christian, it’s like there are two puppies, they’re both hyper, and it doesn’t really balance out that well.”

“I think it’s because I have too much tension on the leash,” Christian admits. “Then when he goes on in front of me, he starts pulling. Cesar’s taught me to relax and let go, to the point where he’s right next to me.” I began working with Christian on the walk as soon as I noticed this problem, because it’s vital that a puppy see every human in the house as pack leader. When I wasn’t around to help, his sister, Sabrina, stepped in. Over the past few months, Sabrina has noticed a big improvement in her brother’s technique. “I think he’s gotten more used to him walking him now. He’s giving him more exercise and he’s playing with him a lot more. And I guess they’re starting to really bond now. Like I can see the trust grow between them.”

Trust and respect are the two most important ingredients of a perfect human-dog relationship. Mastering the walk with your puppy each and every day is the single best way to guarantee a great connection for a lifetime.

CONNECTING THROUGH PLAY

While the walk offers a ritualized, structured way to bond with your puppy, play offers you more varied opportunities to challenge and enrich her life and to build an even deeper connection. Puppies begin to play practically as soon as they can walk, but even their first clumsy attempts at recreation have their own natural rules, boundaries, and limitations. The dominance games they play with their siblings become their very first lessons in social restrictions and canine etiquette. Playing with your puppy should be a big part of your bonding with her as well, but follow the example of nature and remember that play doesn’t have to equal anarchy. Many owners think “play” means letting their puppy just go crazy. It’s better for your puppy’s education and for your own sanity that instead of being a free-for-all, a play session challenges her mind as well as her body. Think about it—we send our kids to soccer practice, which has rules, regulations, and discipline, rather than letting their natural energy build up and cause them to tear through the house, destroying things. Both activities could be considered “play,” but one is productive, the other destructive.

There are two ways a dog will play—one from the dog side of her and one from the breed side. Learning to discern one from the other is the key to making play a fun and positive learning experience, as opposed to an out-of-control riot that may fuel certain unwanted breed-related characteristics in your puppy.

PLAYING LIKE A DOG

All dogs love to run, they all love to chase things (though not all breeds innately know how to retrieve, any dog can learn), and all dogs can track using their noses. One simple game I use to bring out the dog in my puppies while keeping their breed-related tendencies under control is to attach a string to the end of a long stick, then tie a soft stuffed animal—a favorite is a plush duck—onto the string. Then I dangle the string in front of the puppy and move it around in a circle. The tendency for most people would be to move the stick rapidly, working the puppy up into a lather of excitement. Instead, I maneuver the stick slowly, stopping it and starting it. This way, I stimulate both the play and the prey drives in the puppy. The faster she plays, the more physical energy she drains. The slower she plays, the more mental energy she drains and the more she is challenged, since prey drive involves more concentration. This is a good game to play while allowing your puppy to drag a short leash. In this way, the leash and the duck, as well as you, the one who controls the game, don’t come to symbolize overexcitement and chaos. Instead, the entire exercise represents challenge and focus, bringing out the puppy’s animal-dog nature.

In playing games like this that engage the animal-dog in your puppy, you can also begin to observe the breed-related traits that the play or prey drive bring out. When they were three and four months of age, I started playing this game regularly with Angel, the miniature schnauzer, and Mr. President, the English bulldog. There was very little difference in how they played as dogs. Both of them stalked the toy like a dog and chased the toy like a dog.

The breed in them, however, showed itself at the moment they captured the toy. Angel would stalk with his perfect show-dog posture, then muster up the energy to pounce on the duck. After wrestling with it a little, he’d gently let it go and direct his attention elsewhere. Mr. President was calmer than Angel during the stalking phase, but once he got hold of the duck, he would continue to maul it unless I stepped in immediately to make him let go. This is where I have to make sure he plays like a dog, not a bulldog. If he gets into a bulldog state, his play will have no limits. He will actually try to “kill” the toy. It’s much more difficult to remove the toy when a powerful breed’s behavior escalates to that level. If Mr. President—even as a four-month-old puppy—were to get fully into his bulldog state, even food wouldn’t distract him from tearing apart the toy. As long as the puppy’s play stays in the “animal-dog” zone, you can always use the nose to distract him.

A NOSE FOR PLAY

All dogs are born exploring the world first with their noses, then with their eyes, then with their ears. Challenging your puppy’s nose is a wonderful way to engage the “animal-dog” in him—even if he’s a flat-faced dog like a bulldog or a pug. Because of the shape of their noses, these breeds aren’t as sensitive as normal dogs to the scents around them, and they can become addicted to using their eyes as their primary senses in interacting with the world. This in turn can cause them problems. Socially, they can be perceived as more “challenging” to other dogs. It can also lead to behavioral issues if they are frustrated—for example, when bulldogs get obsessed with fast-moving objects such as skateboards and bicycles.

In raising Mr. President to become more dog than bulldog, it was my goal to get him always to use his nose first. One way I went about doing this was through making a game out of hiding his food. I built obstacle courses in the garage, using barriers, boxes, and containers. Then I rubbed the scent of food in several spots throughout the “course” but made a point of hiding the main meal in the toughest place to find. Since Mr. President’s food drive is mighty powerful, this is a wonderful way to get him to engage his nose more than his eyes. This is an exercise I do with all the puppies—with Angel, it is also a way of getting him in touch with the terrier breed in him—but for Mr. President, it will go a long way toward freeing him from the sometimes destructive pull of his bulldog genetics.

OBSTACLE COURSE

An obstacle course is another great way to challenge the animal-dog in your puppy. This is another instance where you don’t need to spend hundreds of dollars on expensive tools and toys—you can use your imagination. An emptied-out box, an old tire, a two-stair stepping stool—anything and everything can be a way to mentally stimulate your dog and challenge her agility. Begin by using food or scent as a lure, then progress to the point where you save the food reward until the end.

Knowing he’d adopted a high-energy terrier with a mind that would need constant challenges, Chris Komives set up his own agility course for his wheaten terrier, Eliza. “Eliza has a strong play drive. I built jumps, tunnels, and other obstacles in our backyard so she could be challenged. She has balls, Frisbees, rope toys, and other toys that are her reward for running through the course. In the evening after returning from our walk but before her dinner, we’ll do some practice for ten to fifteen minutes. On weekends or days I’m not working, we’ll do agility work in the afternoon—again only ten to fifteen minutes at a time.” Chris points out another thing owners must remember when doing mentally stimulating games or conditioning sessions with their puppies: “Being obsessive by nature, I think she was done before I was. If anything, I had to be aware of when I was overtaxing her.” With puppies, short and sweet is always best; think of the old showbiz motto, Keep the audience wanting more.

NURTURING BREED

Once you have fulfilled the animal-dog in your puppy through walks and certain kinds of structured play, next you can introduce her to the world of activities preprogrammed in her by her breed. By fulfilling every side of your puppy’s nature—animal, dog, and breed—you will open up a deeper line of communication, a better channel for intimacy.

Blizzard the Retriever

Blizzard the Retriever

Labrador retrievers are hunting dogs, designed by humans to search out and retrieve prey killed in a hunt. The Labradors have a “soft mouth,” which means they carry their prizes lightly so as not to destroy or mutilate them. This also makes them ideal playmates for children, although the soft mouth of a Lab must be cultivated by the owners from puppyhood. “Blizzard likes to play-bite with Christian,” Terry informs me. “Sabrina will touch him on his neck and snap him right out of it, but with Christian, he really pushes the limits.” My next job is to help the family retrain Christian to provide stronger leadership with Blizzard whenever he begins to use his mouth a little too much.

When it comes to retrieving, all the ingredients are in a Labrador’s genes. But what is inborn doesn’t always come naturally, as John Grogan discovered in

Marley and Me:

He was a master at pursuing his prey. It was the concept of returning it that he did not seem to quite grasp. His general attitude seemed to be, if you want the stick that bad, YOU jump in the water for it. … He dropped the stick at my feet … but when I reached down to pick up the stick, Marley was ready. He dove in, grabbed it, and raced across the beach in crazy figure eights. He swerved back nearly colliding with me, taunting me to chase him. “You’re supposed to be a Labrador retriever!” I shouted. “Not a Labrador evader!”