How to Think Like Sherlock (9 page)

Read How to Think Like Sherlock Online

Authors: Daniel Smith

We all make deductions every day. If we turn on a light switch but no light comes on, we deduce that we need to put in a new light bulb or there is a problem with the electrics. And if we get to the railway station at rush hour and see an empty platform, we might well deduce that a train has just gone or there are no trains running. At the heart of logical deduction is an ability to make leaps of the imagination. Break the process down into manageable stages.

The more evidence, the better you can test out a hypothesis.

The devil is in the detail. It is very often the tiniest details that give away the biggest truths.

Trust in your intuition, but only up to a point. ‘It was easier to know it than to explain why I know it,’ Holmes said on one occasion. ‘If you were asked to prove that two and two made four, you might find some difficulty, and yet you are quite sure of the fact.’ However, it is always well to subject your intuitions to thorough analysis to make sure that what you believe to be a fact is not merely a heartfelt conviction not borne out by the evidence.

Don’t allow your deductive reasoning to be clouded by your personal feelings or prejudices.

Fit your theories to the facts. Do not fit the facts to your theories. In the first instance, you are reading the evidence. In the latter, you are rewriting the evidence simply to accord with your own preconceived ideas.

Beware of the ‘conjunction fallacy’. This is when two or more events that could happen together or separately are considered more likely to happen together than separately. A classic example was provided in a study by the psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman. They provided respondents with the following description: ‘Linda is thirty-one years old, single, outspoken, and very bright. She majored in philosophy. As a student, she was deeply concerned with issues of discrimination and social justice, and also participated in anti-nuclear demonstrations.’ They then asked their respondents which was the more probable scenario: 1) Linda is a bank teller, or 2) Linda is a bank teller and is active in the feminist movement. Eighty-five per cent of respondents went for the second option but by the laws of probability, the answer must be the first.

Just because your conclusion seems odd, even incredible, does not mean it’s wrong. As Holmes noted in ‘A Case of Identity’: ‘Life is infinitely stranger than anything which the mind of man could invent.’ Don’t be embarrassed by the strangeness of a hypothesis if the evidence is there to support it.

Deduction is not a perfect science. Confirm your findings before sharing them. Joseph Bell once wrote: ‘From close observation and deduction you can make a correct diagnosis of any and every case. However, never neglect to ratify your deductions.’

Logic and Deduction Exercises

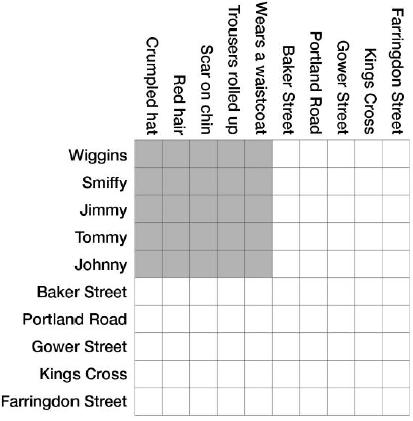

Let’s start with a classic logic grid problem. In this type of problem, there are a number of categories, each containing a number of different options. The aim is to find which of the options are linked together by utilising a series of clues. At first sight it may seem like the evidence does not provide you with sufficient information to reach the one unique solution, but everything you need is there. The grid allows you to cross-reference every possible option in each and every category. The things you know to be true, mark with a tick. Put a cross against those you know to be false. By using deduction, you will eventually find a solution.

Quiz 11 – Most Irregular

Holmes has sent five of the wiliest members of his Baker Street Irregulars to keep surveillance on a gang of bank robbers. Each Irregular must keep an eye on a suspect with a particular distinguishing feature, and each has been assigned to a particular stop on the London Metropolitan line (the stretch of railway line that runs from Baker Street through Portland Road, Gower Street and King’s Cross before finishing at Farringdon Street). From the clues below, can you figure out what distinguishing feature each Irregular will be looking out for and where they have been sent? (Draw the grid on a sheet of paper if you need to).

1.

Wiggins is at Farringdon Street but his ‘mark’ doesn’t have a scar on his chin.

2.

The robber in the crumpled hat is being watched by the boy at Portland Road. The boy watching the suspect with red hair is at King’s Cross but is not called Johnny.

3.

Tommy, who is watching the criminal wearing trousers rolled up at the knee, is at the station immediately after Jimmy.

Quiz 12 – CSI Baker Street

Read through the following perplexing scenes of death. Using your powers of logic and lateral thinking, see if you can deduce what exactly has occurred in each case.

1.

Professor Murray is found hanging in his study. There is no furniture near him but there is a puddle of water beneath his feet. What has happened?

2.

Kenny Adrenalin is discovered dead in the middle of the Sahara. He is face down in the sand, sporting a large backpack. There is no sign of foul play.

3.

Kenny’s brother, Benny, is found dead in the same spot a month later. He too is lying in the sand, naked, with a length of straw in his hand.

4.

Dave Wave, a scuba diver, is found dead in full diving gear in the middle of a forest that has just witnessed ferocious fires. Dave, though, is unburned and the sea is thirty miles away.

5.

A child wakes up and sadly notes the presence of some coal, a carrot and a scarf on the lawn. No one has placed them there. The boy’s father says, ‘What’s up, son?’ The boy replies, ‘It’s Bobby.’ A tear catches in his eye. What has happened?

6.

A man is slumped in the driver’s seat of a car, a bullet wound to the back of his head. The murder weapon is stashed on the back passenger shelf, out of reach of the dead man. He is alone in the car, all the doors are locked and the windows up. What has happened?

II:

Building Your Knowledge Base

Knowing Your Subject

‘It is a capital mistake to theorise before you have all the evidence. It biases the judgement.’

‘A SCANDAL IN BOHEMIA’

Sherlock Holmes was a walking encyclopaedia, wasn’t he? Surely he, of all men, could hold forth on pretty much any subject you cared to mention? The answers to these questions are not as clear-cut as you might expect. Take Watson’s early impression of the breadth of Holmes’s knowledge, as detailed in

A Study in Scarlet

:

His ignorance was as remarkable as his knowledge. Of contemporary literature, philosophy and politics he appeared to know next to nothing. Upon my quoting Thomas Carlyle, he inquired in the naivest way who he might be and what he had done. My surprise reached a climax, however, when I found incidentally that he was ignorant of the Copernican Theory and of the composition of the solar system. That any civilised human being in this nineteenth century should not be aware that the Earth travelled round the sun appeared to me to be such an extraordinary fact that I could hardly realise it.

In the same story, Watson gave this more detailed rundown of his new friend’s areas of strength and weakness: