How You See Me (14 page)

Authors: S.E. Craythorne

Maybe that’s it. Maybe I’m just letting the mess of my rotten life infect you. Or perhaps I smother you? An image comes into my mind. I am walking by a reservoir in the Peak District on a rare day off from Aubrey. Along the line of the water’s edge grow trees, or what used to be trees. They are white as bone; their branches claw the dim sky, leafless and bare. The drowned trees, drinking their own demise, a white iris to the eye of the dark lake. Do I drown you? Is this very letter a splash of ink too much?

Tell me what to do, Alice. Tell me how to fix this. Maybe it is time to lay down my pen and run to you again? I could do that, you know. I would do that for you, no matter the consequences. I will always come, Alice. No matter where you are, I will come to you and it will be as it was before.

Yours, always yours,

Your Daniel

28th March

The Studio

Dear Alice –

I can’t believe you’re not here. You’re really not going to come, are you? Despite everything I said in my letters, you are going to leave me to go through this alone.

I don’t know what I could have said or done differently. I don’t understand this silence. And I don’t know what to do in the face of it. I tried so hard to fit myself into the shape of someone you could truly love. I did everything I could do. I’m sorry I had to leave you, but I thought you understood. This weekend is actually an opportunity for us to grab a little happiness and you have ignored it. You have ignored me. I said I’d chase you, but I don’t see why I should. Am I the only one who cares?

I think I’m angry with you, Alice. It’s an uncomfortable sensation. I don’t want to get used to it. I like loving you.

Daniel

29th March

The Studio

Dear Alice –

Mab, Freya, and Aubrey arrived yesterday.

Aubrey once told me about a homeless woman he used to look out for in Hong Kong – don’t ask what he was doing there, but isn’t it like him? This woman used to wear all the clothes she owned at all times. She would creep along the

harbour paths, surrounded by sweating tourists and sleek businessmen, spherical in her woollen wadding. The only sign of the scrap of flesh that was herself a tiny grinning grubby face, topped with a collection of hats. I thought of that story as I greeted my sister at the door. The only difference was a tumble of hair instead of the hats.

Freya emerged from behind her mother like a vision. Oh, Alice, I am old. Where I remembered a scruffy little girl there was, in her place, a sleek young woman with a head of glossy hair she habitually and confidently tossed over her shoulder as a colt throws its head. She really does glow. She is a beauty.

‘Uncle Dan!’ The tiniest trace of an accent. Freya opened her long brown arms to me and tried for an embrace. I’m so big it would have taken three of her to circle me. Her scent was light and warm as her laugh. She really did seem delighted to see me.

‘Grandpa! Is this wonderful Tatty Dog I’ve heard so much about?’ She left me with the pressure of her kiss on my cheek and some smear of coloured lip grease I didn’t have the heart to scrub from my skin.

Aubrey just looked like Aubrey.

You will be able to tell by this letter that I have decided to forgive you. You have been understanding about my absence; I must learn to be understanding about yours. So, instead of you actually being here, I will help you imagine you are by my side. I’m going to try to detail everything that happens.

We’re all together now in the living room. Mab’s taken my chair by the fire with Freya arranged prettily on the rug at her feet, playing with Tatty, and Aubrey is in Dad’s

evening chair, so I’m perched on the edge of Dad’s bed. Dad’s still sitting in front of the TV, even though it’s been turned off; he keeps turning round and trying to join in the conversation, but the wings of his armchair are hindering him. Mab and Aubrey are doing a pretty good job of ignoring Dad’s existence and mine, which seems a bit rich considering Dad’s the reason they’re here and if it weren’t for me there wouldn’t even be an exhibition. In fact they seem kind of cosy, together in front of the fire. It’s as if they’re plotting something.

I was going to write about what a consolation Freya has been, and then she turned to Mab and started chattering away in French. Then, would you believe it, Aubrey joined in. I am the picture of ignorance.

It feels a little like it used to when Mab came for the summer holidays. I’m forced into seeing the studio through a stranger’s eyes. Aren’t guests always strangers when they first arrive? The place looks grubby and ill-used; Maggie tried to work her magic but claimed there were too many feet under hers and gave up. Personally, I feel invaded. It’s not where I want to be, but it’s my place.

Night-time arrangements have been just as awkward. For some reason, Mab and Freya had to have my room and Aubrey is in the tiny first-floor bedroom on a blow-up mattress. I set up the remaining old cot in the studio for myself and got the blow-heaters running to keep it warm. The sounds are all different here. Next door’s trees with all their bluster are on the wrong side. The floor creaks as if someone is constantly creeping across the boards towards me. I slept badly and told everyone I slept well. In fact, I dreamt I was at sea – easy reading for that one, Mr Freud –

on a storm-tossed boat chasing up and down gigantic waves. At one o’clock in the morning I had to run downstairs to empty my bowels in an ugly rush and sat there for a good ten minutes wondering if I could make it back up to my bed. Don’t they say worse things happen at sea?

I might try to smuggle Tatty up the stairs with me tonight. Her neat round weight can be a great comfort. That’s if I can pull her away from the warmth of the fire and Dad. I’m worried no one seems to have really considered Dad’s role in the exhibition. I’m surprised to find myself feeling protective of him. As Mab, Freya and Aubrey talk, I watch Dad. Back in the bad times when I finally got to Corsica, and actually for all those years in Manchester, I didn’t think I’d ever be able to forgive him. And I knew he would never forgive me. But sitting here now, where we are both ignored in our own house, I find myself in affinity with him.

When he found me with Sarah it was as if I had never really seen his face before. You know how the faces of those you love are so familiar they drift into a kind of soup of features? Dad was just Dad. Indescribable as anything else. That night he introduced himself piece by piece. Fist by fist and boot by boot, he killed my father as he tried to kill me. He would hate that I am here.

While he beat me I thought of my mother. The woman I cannot remember. I thought that finally I understood what she felt as she dove into that river of traffic and off the footbridge where her son waited for her with the homeless man. I imagined the sensation of finally meeting the wheels of the cars which darted, quick fish, below us. The wheels turned like waves, crushing and pounding the asphalt until it cracked and burst and men from the council had to come

and erect plastic barriers and draw chalk lines around the potholes as if they were murder victims. Those wheels burst my mother open. They surrendered her to the detritus of the road, to take her place alongside the crisp packets and fag ends and pieces of broken hubcap along its wasted shoreline. Her indigestible parts.

(Later)

A conversation with Mab:

‘Why are you sulking?’

‘I’m thinking.’

‘Don’t do that, Dan. Bad for your health. What are you scribbling there?’

‘It’s nothing.’

‘More dirty little notes? I hope you’re being sensible.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘Just that.’

‘Have you said goodnight to Dad?’

‘Is it really worth it? He’s hardly going to notice. I’ve seen him all right. That’s enough for now.’

‘You’ve not said two words to him since you got here.’

‘Well, he doesn’t seem to be in a chatty mood. I do my part, Daniel. That’s all any of us can do, isn’t it? Play our parts.’

‘And the weekend? What happens then?’

‘Oh, Michael will be fine for that. I’ve got a friend with a wheelchair we can use. We’ll sit him in the corner with a drink and he can shake people’s hands and they’ll say what a good listener he is and tell him all about his own work. That’s how these things go. You just make sure you keep your head down. I don’t want any trouble, Dan.’

‘Trouble? Jesus, Mab! Who do you think it was who organised all this? Who do you think made all this happen?’

‘Oh, do stop shouting. We all know who’s in charge. Just quieten down or you’ll wake the house.’

‘Has Freya gone up to bed already? I wanted to say goodnight.’

‘My daughter is off limits, Dan. Let’s make that understood right now. Freya is to be left alone. It’s enough that you convinced her she needed to be here. It’s enough that I’ve brought her here; that I passed on your notes. God, look who I’m talking to. No trouble, Danny, just remember that.’

I think Mab is more worried about the mask performance than she wants to admit. I did offer to take over the organisation for her, but she just snapped at me. She seems so distracted and preoccupied. Maybe all these years as a single parent have worn her down. She certainly seems confused, I mean, who tells a person to stop shouting and then yells at them?

Love me better, Alice.

Your Daniel

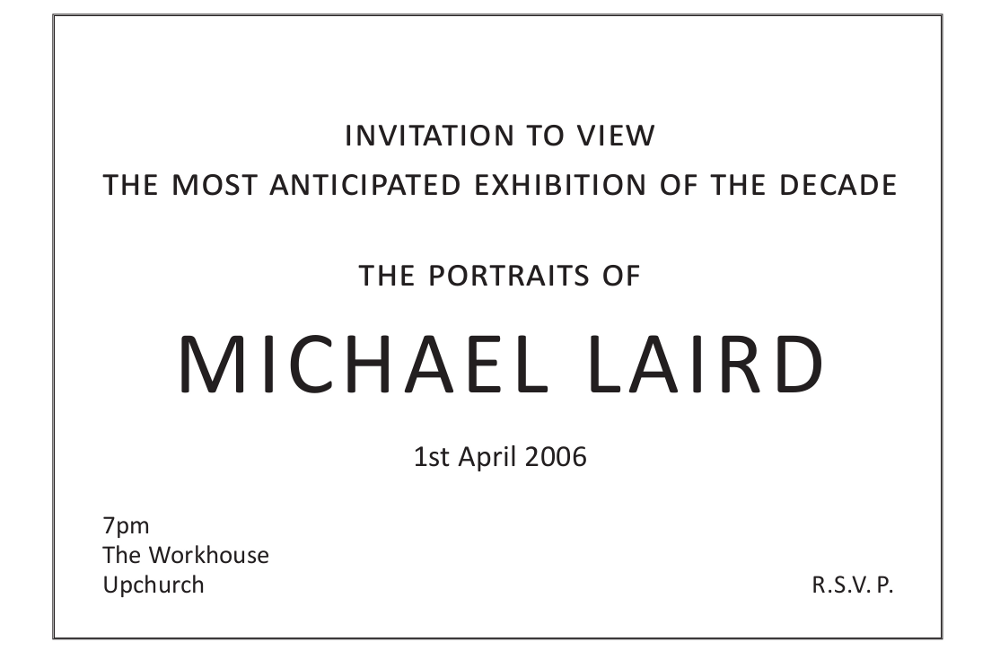

31st March

The Workhouse

Dear Alice –

We sit in front of a lit stage, watching the occasional figure in black trousers and black polo-neck cross the floor with frowning intent but no apparent purpose. Mab has

taken her place on the front row. I can see her brushing her wild hair out of her eyes. She’s knelt over the back of her chair talking to a similarly wrapped and draped woman, who was introduced to me earlier as an up-and-coming sculptor from Croydon. Mab sees me watching her and winks. At least she seems to have cheered up. Then I realise Freya is sitting a couple of rows behind me. Perhaps the wink was for her?

The drinks were served early and the audience is loud and informal. They all twist round in their chairs, glass stems between loose fingers, and talk and laugh and complain. Reassuring themselves, with furtive glances around the room, that every other guest is as recognisable and as important as they consider themselves to be.

This is quite a novelty for them. For once they don’t have to worry about the possibility of a better party across town. They are stranded here. There is nowhere else to be. They are ready to be entertained by whatever comes their way.

The one silent spot in this busy hall is settled over Aubrey and me. Even Freya is busy with a crowd of admirers – all shopping for a new muse, no doubt. I’d like to be able to intervene and protect her, but the flow of people through the room seems to conspire against my interference. I sit writing to you with Aubrey beside me. He keeps trying to enter the conversations around us with his standard smile and bluster, but nothing sticks. It’s really quite funny to watch. He even turns to me in the hope of starting something of his own, but I absorb myself in writing. I won’t play. He’s looking at the stage now. The only one in the room to do so. He’s forgotten to stop smiling.

One of the polo-shirts is making his way to the light switch by the door. There’s some coughing and scraping of chairs. Prosecco is being tipped down throats all around me, as they ready themselves for the show. They’re more attentive than I thought.

(Later)

So, as you’re not here, I must bring the show to you. To be honest I’m grateful for a chance to escape the party. They’ve cleared the chairs away now and the drinking has begun again in earnest. Someone’s thought to set up a CD player and there’s some soothing classical mix playing, but the atmosphere is more like that of a house party or a wedding reception disco. I’ve found a quiet corner, behind one of the improvised wings, where I can watch and record without being disturbed.

The actors circulate with their masks slung over their hands, like waiters with unusual platters. Their effect on the crowd seems greater than that of the alcohol. I just saw a man in a three-piece suit conduct a long, animated conversation with one leering half-mask, while the actor holding it kept up the mask’s end with shifts of his hand to mimic nods and querying tilts. There is too much laughter and it’s all too loud. Something has been shaken loose. This night will last till dawn.

The performance started with one Mask on the stage. This one was a talker. It surprised me, because Mab had warned me that Masks usually have to be taught to speak. This one babbled on, moving across the stage swiftly and with great confidence, but still with the air of something

otherworldly in the rigid features frozen above his wet and mobile mouth. He played with the audience, fondling one man’s tie and then stealing a woman’s scarf and knotting it carefully around his own wrist. He laughed at their faces and mocked them roundly. But it was all very good-natured. The victims seemed delighted by his attentions and I saw others shifting forward in their seats, hoping to be among the chosen. The mask itself was a good one, half-face, heavy-nosed and heavy-lidded. The actor had taken on a foreign accent of some description and he couldn’t seem to stand still. It was all strangely captivating. Like watching a man go mad and being allowed to laugh at him.