Humor (4 page)

Authors: Stanley Donwood

Having at last completed work on my time machine, I am disappointed to find that it does not work beyond the parameters of my own life. I can travel back to my childhood years, observe myself behaving insufferably as a teenager, see myself as a tottering octogenarian; in effect I can visit any period of my relatively mundane life, but cannot travel to the past that I missed or the future I will never see. To compound this problem, I cannot actually touch, taste or smell anything during my already uninteresting travels.

No one in the past or future can see me. I attempt to speak with myself, warn myself about imminent dangers, shout ‘don’t marry her’, and so on, but all that escapes the confines of my mouth are little puffs of carbon dioxide. The whole time-travel thing seems horribly reminiscent of my experience at parties.

Back in my laboratory, I extricate myself from the spidery apparatus of the time machine, and stare wearily from the bleary windows.

I am invited to a party that is being hosted by some old friends. As usual, I get to the party early and stand awkwardly outside the gates to the house. It is dark but warm, and unknown creatures speak to one another in the night.

I step hesitantly into the overgrown garden, and notice a light on in the house. Although the party may not have started, I convince myself that my hosts need help with the preparations. I am a dab hand at samosas.

Easing my way through the conifers that bar my progress, I approach the lighted house. Intending to play a minor joke, I peer in through the window, and I am surprised to see two Aliens from Outer Space conversing in the drawing room. They appear to be engrossed in a clever discussion, and I withdraw quietly, not wanting to disturb them.

After loitering outside the front gate for some time, I make my way back home, now sure that the party is either not going to happen or that I have inadvertently entered another dimension.

About a week later, I come across one of my old friends in a café. He asks me why I wasn’t at their party. I make my excuses and leave.

My brother calls me at home, and we discuss our respective social lives. My brother complains of a boredom with

life, while I counterpoint with a distrust of parties in general and clever Aliens in particular.

Eventually, we agree to finish the conversation, but as I put the phone on the hook I am seized with terror. Quivering, I run a bath, aware that both my reactions and my emotions are ill placed.

I am driving a fast car along the beautiful cliffs that line the road between London and Brighton. My mind is aflame with lust. To my left gleams the azure Mediterranean, while on my right the chalk cliffs flash in the sunlight.

I am increasingly worried as the car gathers speed, as it seems that my brakes have been sabotaged. Faster and faster, the cliffs flick past. I am forced to do some clever manoeuvring until I skilfully skid to a halt in Brighton, where my lover awaits, resplendent in a velvet-lined apartment overlooking the shingle beach.

We engage in inventive sexual games while hooligans roam the wet streets below us.

I am queuing at my nearest out-of-town supermarket when an unpleasant scene begins to develop. Three shop assistants haul a muscular but dead young bullock out from behind the translucent flaps that guard the inner sanctum of the store, and lay it on the tiles in the tights, socks and toothcare aisle. Another assistant emerges with several large knives, and the four of them stand around the carcass as if awaiting silent instructions.

As one, they flash their knives and one of them makes a large cut in the hide of the bullock. Another slices deftly at the neck area, while the third and fourth make incisions around the jaw. The two assistants nearest the head lay their now-bloody knives on the clean tiles, and, with visible effort, insert their fingers into the gashes they have just made. They begin to pull at the thick, hairy skin of the bullock, tugging hard until the flesh begins to pinkly emerge. They pull and pull, and the hide slides back over the jaw. As the skin comes back, to my horror, the bullock’s eyes begin to flicker.

At the moment the hide rips back over the eyes, they widen, and the bullock staggers to its feet. The assistants pull harder and harder, but the bullock charges away towards the delicatessen counter, its face flapping wildly around its flayed skull. I am close to fainting, although I

cannot, as I have been queuing at the checkout for what seems like an age. At last, my items are scanned and I pay for them, my Visa card shaking in my hand.

I am sitting outside my favourite bar, drinking coffee and smoking quietly. In the distance, through the heat and softly settling dust of siesta-time, I hear a faint clattering and chanting. I turn towards the sound, straining my ears.

After several minutes have brought the noise closer, I realise that it is the music of a grand religious procession of some kind.

My suspicions are confirmed when a colourful scene bursts into the stillness of the square. In the centre of a mass of Aztecs are a royal couple, hoisted up on an elaborate double throne. The Aztecs are all expressionless, their eyes blank and dead as they chant and sing.

I glance nervously around, but I am the only person in the square. The bar appears long closed, and my coffee is cold. As the Aztecs turn to stare vacantly at me, I feel certain that I should be elsewhere.

I unfold from my chair and bolt along a narrow alleyway between tall buildings, the washing lines flapping high above my head as the baleful roar of the Aztecs echoes from the square. I run this way and that, my heart pounding and my face streaming with sweat. I am lost, and in a blindly unreasoning panic.

I find myself alone in a frightening building at the dead of night. I am filled with an eerily familiar mixture of fear and rage. I reason that I could either curl up on the floor and whine pathetically or take responsibility for my inner anxieties and act with certainty.

I decide on the latter, and call out the name of my personal demon and psychic tormentor. I repeat this shout with increasing volume several times, until he appears, reeking of evil and smouldering foully. My fury overcomes a sudden feeling of spiders crawling in my duodenum, and I launch myself at the demon, screaming an assortment of obscenities, pummelling him viciously. As I punch, he seems to diminish in size. I continue to beat him, until there is nothing left of him except his Doctor Martens boots, which I fling from the window into the night with a callous laugh.

Subsequently, I am unable to sleep at nights, as I worry greatly that there may have been something of the demon still left in the toes of the boots. I attempt to find them, but the frightening house is not on any street in my town. Weary now from sleeplessness, I wait in my room for the demon to return, and regret deeply having behaved so decisively.

The hazards of city life take their toll, and I move to a small seaside town built of wooden houses. Unfortunately I become involved in a dispute with my next-door neighbour. That matter escalates to the point where he feels the need to involve his hard-drinking friends.

One evening, drowning my sorrows at the tavern, I learn that my neighbour plans to burn down my house. The information distresses me considerably, and I decide to take evasive action. Returning to my house, I turn on all the taps, and with a hose I drench the walls and contents of the building. I sneak out of the flooded kitchen and hide in nearby sand dunes.

Sure enough, later that night my neighbour and a gang of angry drunks approach my house with flaming torches. In vain, they try to set fire to the soaking wooden structure, but it is simply too wet to catch light. Hidden in the dunes, I chuckle with delight at having outwitted my neighbour.

The next day, in the grocery store, I am pinned to the wall by the shopkeeper. He tells me he is good friends with my neighbour, and accuses me of underhand tricks. I tell him I don’t know what he means, but he says no one but me would deliberately drench their own house with water simply to spoil his neighbour’s fun. He tells me that killjoys like me have no place in a real community.

At home I sit on the wet sofa, pondering the nature of my existence. Later I wander the house, turning off the taps, one by one.

I am disturbed to discover that my colleagues have invented a new game which seems to involve attempting to kill me in every juvenile way that presents itself to them. They delight in surprising me with shoves into the paths of oncoming double-decker buses, constructing ridiculous rope-and-pulley devices with the aim of dropping heavy furniture on my head, placing tripwires at the tops of escalators, and other such inanities.

They persist for some weeks, during which I become increasingly adept at avoiding sudden death by blackly humorous means. I feel that my senses are sharpened day by day, that my sight is keener, my reflexes quicker.

Soon I can detect by the smell of linseed oil alone the presence of a cricket-bat-wielding acquaintance in the bathroom. Everything is enhanced. Colours are richer, noises are louder. I awaken to the pattern of life, the weight of deeds.

Eventually my heightened awareness evolves into a vividly focused paranoia. I can only retreat; I move surreptitiously to a small seaside resort on the east coast and wait, slowly, for a death of my own choosing.

I am alone in a hot city. My favourite bar is closed for siesta, and I am aimlessly walking the dusty streets. Outside a shabby tailor’s, I am accosted by a man in a dark suit. He acts in a conspiratorial manner, and invites me to follow him along the street.

After some time, we arrive at a small bar on the edge of the city. We take a seat each, and the man whispers to me that he is suffering from an unusual complaint, in that he is consistently late for everything. He explains that this is because somebody has stolen his today, forcing him to take up residence in tomorrow. As a consequence, every engagement he makes can never be honoured. He is always late, and wakes up in the morning with a terrible sense of guilt and failure. When he saw me outside the tailor’s, he recognised a kindred spirit, he tells me.

I tell him that he is quite mistaken: I may be renowned for my lateness, but I have been on time on occasion, and no one has stolen my today. This visibly disappoints the man in the dark suit, and he makes his apologies and shuffles off, out of the bar. I am left feeling a little guilty, but I reassure myself that there is nothing to feel bad about.

That night, I am seized with the idea that someone has stolen my today. I find, the next day, that I have missed all my appointments by twenty-four hours.

At siesta, I see a man in a dark suit greeting an acquaintance with a firm handshake and a smile. I overhear the words ‘Glad you could make it.’

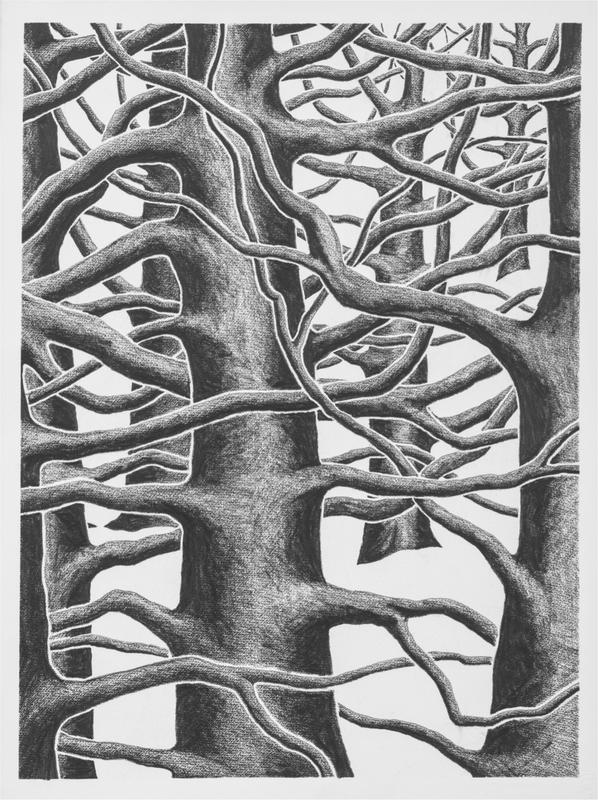

I make a daring escape from a maximum-security prison camp, and, after effecting my egress from the moist tunnel, plunge headlong into the trunky darkness of the pine forests that encircle these regions.

I scramble beneath the needled branches for some time before I realise I have a pair of garden shears embedded in my stomach, the weathered handles protruding in the direction of my escape. I attempt to wrench them from my flesh, but the pain is too great. Reluctantly I leave the shears in my belly, and stumble onwards.

With deepening anxiety, I become slowly aware that, with each step, the blades of the shears move infinitesimally closer, cutting into something vital that is deep inside me.

I have no choice but to continue, and as dusk cloaks the forests I finally emerge into the open plains. I climb, with panting breaths, a ridge and stand there, horribly conscious, gazing towards a dubious future. The shears are almost closed.

During a period of poverty more pronounced than usual I consider applying for a job. A concerned friend suggests that I try for a place at the restaurant where she was, until recently, employed as a waitress. The most usual position to come up is that of dishwasher. My friend warns me that dishwashers are considered the lowest of the low, an underpaid subclass treated abominably. She tells me that in a restaurant there is a structured hierarchy of abuse; the owner harangues the manager, who insults the chef, who turns angrily on the preparation staff, who vent spleen on the waiting staff, who then unleash their fury on the dishwasher. The dishwasher has very little room for manoeuvre in this concatenation of spite. I assure my friend that I will be fine, and ask her for directions to the restaurant. The chances are that I will not need the job, that something will turn up.

A week later my financial situation has not improved, so I take a bath, put on some relatively clean clothes and walk to the restaurant. The manager cannot see me as he is ‘off sick’, but after a lengthy wait I am summoned to the office, where the assistant manager introduces herself to me. The office is small, and smells of things that I cannot identify. She asks me why I want the job. I say I had always wanted a career in catering. She asks me if I have any experience,

and I reply that I am keen to learn. She wants to know if I work well as a team member, whether I am what she refers to as a ‘people person’ and also whether I have any prior convictions. After a passing reference to the conduct expected of her employees, she outlines my responsibilities and the hours I will be required to work.

I ask her if that means I have got the job, and she answers that she will be in touch. I leave the restaurant with mixed feelings. On the one hand, I think I dealt with the interview quite well. However, I failed to get the last job I applied for, and that was only to work as a shelf stacker – or, rather, replenishment operative – at a down-market superstore near the ring road. But essentially I feel positive about my prospects.

Three days later I receive a telephone call from the assistant manager. She enquires about the possibility of my working in the kitchens that evening. I ask her if that means I have got the job, and she answers that we will have to see how things go. This evening’s work will be both a ‘trial period’ and a ‘training session’. I want to know if I will be paid for the work, and she tells me that ‘training periods’ are not paid. In fact, she adds, with something of a giggle in her voice, perhaps I should pay for this training. I laugh sycophantically and put the phone down. The sky outside begins to rain, and I look around my room, as if for the last time.

The restaurant is very busy. There is a queue outside, and the waiters and waitresses look harassed. I am hustled through the dining area to the kitchen, which I see houses two red-faced, angry chefs, three furious prep staff, and

two large unattended sinks piled high with dirty dishes and pans.

My ‘training session’ involves a great deal of washing up. The clientele of this particular restaurant seem to make a lot of mess, and appear to delight in stubbing cigarettes out in their unwanted burgers, fried eggs, prawn cocktails and pork chops. I am also introduced to The Pig, which isn’t a pig but rather a large metal machine. The Pig is kept in the very back room of the restaurant, along with large empty metal tins that once contained cooking oil and empty cardboard boxes. I pour food scraps scraped from plates into a bucket, which I then tip sloppily into one end of The Pig. I press a green button, and The Pig shakes and emits a terrible noise made of crushing bones and churning matter. When the noise subsides and the food scraps are all gone I press a red button, and The Pig shudders to a halt. Then I return to the sinks and try to catch up with the piles of crockery that have accumulated during my time away.

By the end of the evening I am very tired, but the assistant manager calls me aside, and she insists that I join her and some of the waiters for what turns out to be four hours of lager and a great many cigarettes. We all agree that the catering business is a tough business that attracts people who are the ‘salt of the earth’. I feel very agreeable when I finally get home, and I fall asleep easily, dreaming only of detergent and the sound The Pig makes as it digests the leftovers.

In the morning I feel considerably less sanguine. When I remember that I agreed last night to a shift at the restaurant starting at one o’clock I groan loudly and slump back into

my bed. I realise that I worked for six hours and have nothing except a headache. Outside the sky is raining again and the seagulls are mocking me.

At around half past one I walk through the dining area to the room at the back. The assistant manager looks very cross, and tells me that she will be docking my wages because of my lateness. She asks me if I have ‘punctuality issues’. I say that I have not, and ask her how she can dock wages that I don’t have. This is the wrong thing to say.

Later, when I am called upon to clean out the pork buckets, I realise my headache has subsided. The job in hand is, however, so thoroughly nauseating and dispiriting that I take advantage of a lull in the restaurant’s activity to step outside for some fresh air. The assistant manager joins me and offers me a cigarette. She begins to tell me that she isn’t really a bitch and when she was a little girl she wanted to be a ballerina. Because the fucking manager is ‘off sick’ she has to do all the fucking work and really she wants a quiet life in a cottage in the country. It would be different if she was the manager. For a start she would be able to afford a better car and a better house. I sympathise, and then decide to take advantage of her mood and ask about my wages. She glares furiously at me, asserts that I drank them last night, had the temerity to turn up late on the busiest day of the week, and adds that the only reason she hasn’t sacked me already is because she is a good person and is determined to give me a chance.

During this interlude both of the sinks have filled with plates and cutlery, and wearily I begin to empty one sink so I can fill it with water and detergent. After scraping the

plates free of unwanted food and greasy cigarette butts I take the now-full bucket to The Pig. I press the green button, and feed The Pig with something approaching tenderness. Soon I will be forced to share its diet. I can see myself squirrelling choice leftovers into my pockets to be devoured later, out of sight of the rest of the staff.

Eventually the last customers leave the restaurant, meaty arms draped around one another. My chores keep me busy for another half an hour, and when I hang up my apron and head for the door I am stopped by the assistant manager and invited to share a table with her and three waiters, one of the chefs and two of the food-preparation staff. I protest, saying that I cannot afford to spend any more of my wages on lager. They look confused, until the assistant manager says something quietly to them, whereupon they burst out laughing. It seems that the assistant manager was only joking with me about that particular matter. The lager is a perk of the job, a fringe benefit. It occurs to me that to have a fringe you ideally need a main event, such as a wage, for the benefit to be attached to. However, I am too tired to mention it, and drink lager for several hours. The assistant manager may have wanted to be a ballerina, but the chef had always dreamt of a career in the army, two of the waiters were actually ‘resting’ between acting jobs, the third intended to be a comedian, and the food preppers both intended to become property developers.

The night ends in raucous laughter, toasts to the ‘salt of the earth’ (ourselves) and jokes about how ill we will all feel in the morning. I stumble home through the rain, thinking generous thoughts about my co-workers, and

eventually fall into a sleep filled with dreams about the glutinous matter that stubbornly adheres to the bottom of the pork buckets.

I am awoken from my gritty sofa by a determined hammering on the front door. It is my landlord, who wishes to collect the last two weeks’ rent. I clutch at my temples and tell him about my new job. This seems to assuage his incipient fury, as long as I pay him as soon as I get my wages, and he leaves, muttering dark threats about bailiffs. This morning, I realise, will not be productive. I trudge up to bed, anxious to sleep the remaining hours until my one o’clock shift begins.

I make pains to arrive on time, and the assistant manager nods curtly at me as I don my apron. I know for certain that I am extremely hungry, but the leftovers I scrape into the bucket repel me, coated as they are in cold, coagulated grease and studded with crushed cigarette butts. I ask the chef who wanted to join the army if I can have a burger. He flips one over and passes it to me on a metal spatula, warning me that it will ‘have to come out of my wages’. I am not sure if he is joking or not, and he turns his red face back to the griddle before I can ask him.

The burger is still pink and raw at its core, but I eat it rapidly, feeling a surge of energy almost immediately. I redouble my vigour with the dishes and pans, and before long the bucket is full of waste food. I go to feed The Pig, and it gurgles as I feed it. I have saved the leftover desserts for last, and The Pig lets out a contented belching sound as I pour in melted Knickerbocker Glories. But then there is a terrible sound of grinding, a shrieking, shearing noise

that fills me with alarm. Hastily I press the red button, and The Pig judders on the concrete floor before falling silent. For a minute or two I stand still, the empty bucket in one hand, the other hand hovering a few inches away from The Pig.

When I tell the chef who wanted to join the army what has happened he too stands motionless for a short time. Then he turns to face me, shaking his head, and says that I’d better go and tell the manager. I remind him that the manager is ‘off sick’. He says that I had better tell the assistant manager, then. Still shaking his head, he returns to the griddle. With trepidation I leave the kitchens and wait in the busy dining area until the assistant manager notices me. She walks rapidly towards me, flicking her finger to remind me of my grease-smeared clothing and generally unkempt appearance, and she mouths unfriendly words. The force of her personality pushes me back through the door into the kitchen, where she stands very close to me and asks me what exactly do I mean by barging into the dining area like that. I explain the dreadful noise that The Pig made, and she marches through to the back room, with me scurrying at her heels. She presses the green button, and again The Pig makes that hideous screaming noise. The assistant manager presses the red button and turns to me, her eyes narrow slits, her face red, her whole body shaking slightly. I find difficult to imagine that this woman could ever have dreamt of tutus and ballet pumps. I picture her in them, and release an involuntary smile with my mouth. This is the wrong thing to do. The screaming that comes from the assistant manager is even worse than that

which came from The Pig, which was at least non-verbal. She calls me a great many names, implies that my brain is retarded and that I am impotent, that my penis is smaller than her little finger. It seems that I have inadvertently fed The Pig a piece of cutlery. This will do terrible things to the grinders, she says. She tells me that because she is only the fucking assistant manager she cannot sanction calling in the fucking mechanic. I ask if we can’t telephone the manager and ask him to sanction it, but she spits furiously at me that he. Is. Off. Sick. And then she tells me I now have to empty the buckets of scraps into the empty cooking-oil cans, and she storms off, to get back to some real work and away from fucking imbeciles such as myself. Oh, and the damage to The Pig, when it has been costed, will come out of my wages.

This is bad. The empty oil cans are quite large, but after three shifts here I know how much waste is fed to The Pig. There are only about twenty of the oil cans in the room, and I calculate that they will be full after the end of this evening. But there is nothing I can do. I am in disgrace in the kitchen. Nobody speaks to me, and I tend to the sinks, washing dishes, drying cutlery and so on until the prepping staff wordlessly push the pork buckets across the floor to me. On my trips to the back room The Pig sits idle while I pour the slops into the cooking-oil cans. The room begins to smell quite abominable, and I worry that the ghastly odour of the intermingled food waste will drift through the dining area, getting me into even more trouble. I wedge open the top window, hoping that the smell will be drawn out into the night air.

After work I am not invited to drink lager with the others, and make my way home disconsolately through the rain. I have no food at home, and nothing to drink except tap water. I sit for a while looking out of the window, and then suddenly I have an idea.

I leave the house, and walk briskly. The rain has stopped, and although it is still very windy the sky is clearing, and stars are visible through the orange haze of the city. In the alley which the restaurant backs onto I see that the top window of the back room is still wedged open, as I left it. I find a crate and stand on it, reaching through to unlatch the larger part of the window. Once inside, I close the window and turn on the light. Any hopes I might have had of salvaging something to eat from the oil cans are immediately quashed by the foul state of the mess within them. Then I realise: of course! The kitchen is full of food. I can help myself! Once in the kitchen I help myself to several prawn cocktails, a salad and some of the burger buns. I look longingly at the frozen burgers and decide to try to turn the griddle on. I place several frozen burgers on the bars, figuring that what I cannot eat now I can take home with me.

Suddenly I feel quite full, and sit outstretched on the floor. Then I begin to feel guilty. If the assistant manager finds out about this I will be quite done for. Not only will I get the sack without even having got paid, I will actually owe money for breaking The Pig. By now the food must be sustaining my mental faculties, for I have another brainwave.

In the back room I find a spanner, and study The Pig. It looks as if I can remove the side plate, which should

reveal the inner workings. I am not of a mechanical bent, but I reason that it should be relatively easy to locate the errant piece of cutlery and extricate it somehow from the grinders. So I kneel to undo the bolts on the side panel and work it free from its housing. And then, in a gusting rush, a tide of revolting slop shoots out of The Pig, drenching me and spreading rapidly in a noisome flood all over the floor. The stench is atrocious, and without being able to stop myself I vomit copiously again and again, desperately crawling backwards through the filth on my hands and knees away from the still-flowing river of macerated burgers, egg, bread, prawns, cigarette butts, pork and various accompanying dishes.