Hundreds and Thousands

Read Hundreds and Thousands Online

Authors: Emily Carr

Tags: #_NB_fixed, #_rt_yes, #Art, #Artists, #Biography & Autobiography, #Canadian, #History, #tpl

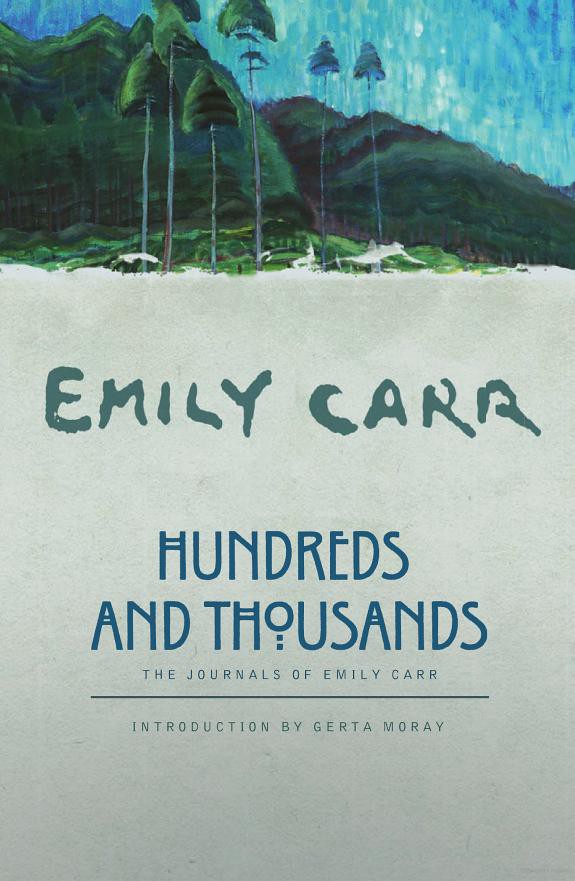

HUNDREDS AND THOUSANDS

Emily Carr,

Odds & Ends

, 1939, oil on canvas, AGGV1998.001.001.

Formerly in the collection of the Greater Victoria Public Library,

transferred to the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria.

THOUSANDS

EMILY CARR

THE JOURNALS OF EMILY CARR

INTRODUCTION BY GERTA MORAY

Copyright © 2006 by Douglas & McIntyre

Text of

Hundreds and Thousands

copyright © 2006 by John Inglis, Estate of Emily Carr

Introduction copyright © 2006 by Gerta Moray

06 07 08 09 10 5 4 3 2 1

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval

system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior

written consent of the publisher or a licence from The Canadian Copyright

Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For a copyright licence,

visit

www.accesscopyright.ca

or call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

First published in 1966 by Clarke, Irwin & Company Limited

Douglas & McIntyre Ltd.

2323 Quebec Street, Suite 201

Vancouver, British Columbia

Canada V5T 4S7

www.douglas-mcintyre.com

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Carr, Emily, 1871–1945.

Hundreds and thousands: the journals of Emily Carr/

Emily Carr ; introduction by Gerta Moray.

ISBN-13: 978-1-55365-172-7 • ISBN-10: 1-55365-172-3

1. Carr, Emily, 1871–1945—Diaries. 2. Painters—Canada—Biography. I. Title.

ND249.C3A2 2006 759.11 C2006-900824-8

Editing by Saeko Usukawa

Cover and text design by Ingrid Paulson

Cover painting: Emily Carr, detail from

Odds & Ends

, 1939, oil on canvas,

AGGV1998.001.001. Formerly in the collection of the Greater Victoria

Public Library, transferred to the Art Gallery of Greater Victoria.

Printed and bound in Canada by Friesens

Printed on acid-free, forest-friendly (100 per cent post-consumer

recycled) paper, processed chlorine-free

Distributed in the U.S. by Publishers Group West

We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Canada Council for the Arts,

the British Columbia Arts Council, and the Government of Canada through the Book

Publishing Industry Development Program (BPIDP) for our publishing activities.

INTRODUCTION: AN UNVARNISHED EMILY CARR

by Gerta Moray

PUBLISHER’S FOREWORD TO THE FIRST EDITION

MEETING WITH THE GROUP OF SEVEN, 1927

A TABERNACLE IN THE WOOD, 1935

by Gerta Moray

AS WE READ EMILY CARR’S

journals, we realize we are looking over the artist’s shoulder as she writes down her most intimate day-to-day thoughts and experiences. In these pages, she records her conversations with herself, her thoughts about her art and her search for a meaning in life. We witness her frequent anger and guilt towards family, neighbours and colleagues, her emotional life of alternate elation and depression, and her frustration at the struggle to earn a living as a landlady while attempting to be an ambitious modern painter in a provincial town. The journals provide a fascinating window into the personality and subjective experience of an artist and human being. Their stream of consciousness reveals Carr’s search not for peace but for vitality, for a sense of life as change and movement. The journals also reveal her intense appetite for connection — to the surrounding world of nature, so lavish on the Northwest Coast, and to the more difficult world of human relationships. They show how she sublimated these longings into art through bold orchestrations of visual form and through striking prose poetry, as well as through explorations of an eclectic new language of

religion emerging in her time. But we must realize that Carr’s stream of consciousness, unlike that in the novels Virginia Woolf was writing at the same time, was not composed with a view to publication (more of that later), that the journals were never considered, structured, pruned or polished for a critical reader’s eye. They therefore give us an Emily Carr exposed and vulnerable to judgment. Most readers will either love or hate her journals, or even both at once, depending to a great extent on their temperamental and experiential common ground with the writer.

Some background information on the publication history of the journals, on their context as writing and on their relationship to Carr’s life history and artistic career, will offer a broader basis for understanding and interpreting what is recorded in

Hundreds and Thousands

. First of all, there is the book’s publication in 1966, more than twenty years after Carr’s death, and the incorrect statement about its origins launched by her publisher. “From letters found among her papers,” the publisher’s foreword claims, “we know that Emily Carr intended her journals to be published. She even thought of the title,

Hundreds and Thousands.

” Carr did indeed invent this title; however, it was not intended for her journals but for a collection of short stories of her childhood that she was composing during 1943–45. And when, in the author’s preface (provided by the publisher from a note found among Carr’s papers), she commented that “these little scraps and nothingnesses of my life have made a definite pattern,” she was referring not to journal entries but to memories of her youth that she was intent on recapturing in literary form. In letters to her friend Ira Dilworth during 1943 and 1944, she makes repeated references to her work on these short

sketches. On July 6, 1944, she sent him a list of twenty-four of them, commenting that “Of course I may twist and cut & abolish and I shall peel & peel & cut out every word I can and still leave them something to tell. I want to get them rough-typed … so that my thoughts are there.”

1

These stories she left in her will, together with her other manuscript material, to Dilworth, who had acted as editor for the three books by her that were published during her lifetime:

Klee Wyck

(1941),

The Book of Small

(1942) and

The House of All Sorts

(1944). Her publisher, William H. Clarke, manager of the Toronto branch of Oxford University Press, and his wife, Irene, had became friends of Carr’s, and in collaboration with Dilworth they published three further volumes of her stories after her death, starting with her autobiography,

Growing Pains

(1946), which Carr considered too outspoken to be published during her lifetime. This was followed in 1953 by

Pause: A Sketch Book

and

The Heart of a Peacock

. Dilworth then began the arduous process of transcribing the handwritten journals for publication, convinced of their literary merit and of their great value in revealing aspects of her artistic intentions and processes. A newspaper report in 1945 records that when he made an official speech at the opening of Carr’s posthumous memorial exhibition, “Mr. Dilworth told of finding, in a box left for him at her death, Emily Carr’s journals. ‘My hands trembled and, as I read, my spirit trembled, for I felt myself in the presence of a great creative spirit.’”

2