Hungry City: How Food Shapes Our Lives (31 page)

Read Hungry City: How Food Shapes Our Lives Online

Authors: Carolyn Steel

Contrary to appearances, the immaculate world of modernism involved as much denial as did the era it sought to replace; arguably,

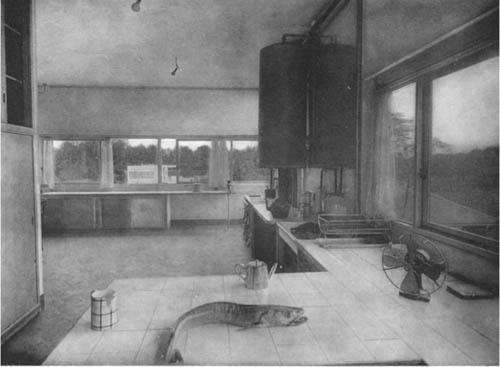

even more. At least Victorian house-builders had agonised openly about how to hide the bowels of their buildings; modernists simply edited them out of the frame. Although bodily needs were central to modernist rhetoric, the references were all of the ‘pure’ variety: the need for exercise, light and air. ‘Other’ bodily needs were suppressed. At the Villa Stein-de Monzie, structured by Le Corbusier around a series of outdoor terraces upon which the owners were invited to cavort half-naked, the kitchen was as hidden as that of any Victorian house. Yet official photographs show it to be an immaculate space full of light, its gleaming worktops barely hinting at the use to which they might be put. A carefully arranged raw fish and coffee pot are the only allusions to the room’s real purpose. Designed to be hidden from the owners of the house, the kitchen is nevertheless allowed to appeal directly to the anonymous eye of aesthetic judgement. Whiter and shinier-than-thou even in its dirty bits, the Villa Stein-de Monzie was an icon of wipe-clean architecture: fetishised, purified space that could only be spoiled by the mess of human inhabitation.

In his 1933 essay

In Praise of Shadows

, the Japanese author Jun’ichiro Tanizaki remarked on this growing tendency in the West to shun the ‘other’ side of human nature – the dark, the dirty, the old, the worn out – in favour of sanitised perfection. ‘Westerners attempt to expose every speck of grime and eradicate it,’ he wrote, ‘while we Orientals carefully preserve and even idealise it.’

63

And in this newly polarised Western view of the human condition, cooking somehow ended up on the ‘wrong’ side: that of filth rather than health, work rather than pleasure, solitude rather than sociability.

The kitchen at Villa Stein-de Monzie in 1926.

Despite the best efforts of early feminists to raise the status of cooking, they failed to address one essential fact: their contemporaries had no more desire to cook than their ancestors had. Hygiene and efficiency were all very well, but they weren’t much fun – and the fact that every household guru from Catherine Beecher to Grete Lihotzky had denied there was any pleasure to be had from cooking hardly helped. To have admitted that cooking for its own sake might actually be

enjoyable

would have risked undermining one of the central props of feminism. Better to insist on it as a science or profession; at least that way, one could pretend that it was not the thankless drudgery that, deep down, everyone really believed it to be. With so much subterfuge surrounding their early development, it is hardly surprising that modern domestic kitchens evolved into such ambiguous spaces. By the 1920s they had become highly sophisticated machines for cooking in. The trouble was, no one wanted to cook in them.

American women had another reason to be reluctant to cook. The Depression meant that increasing numbers were having to go out to work, and for those who remained at home, economic hardship removed any vestiges of pretension about lab-coated housewives, reviving instead the much older tradition of the hardy homesteader’s wife, with her make-do indomitable spirit. The new role was epitomised by

American Gothic

, a 1930 painting by Grant Wood in which a plainly dressed couple (she with gaze averted, he clutching a pitchfork) stand resolute outside their clapboard Iowan farmhouse. The portrait

captured the pioneer spirit of small-town America, but increasing numbers of women no longer lived there. They lived in cities and worked for a living, and were still expected to conjure up wholesome meals for their husbands every night. The stage was set for the creation of one of the twentieth century’s greatest fictions, the domestic goddess – the product not of painterly imagination, but of something even more potent: advertising.

To nascent American food-processing companies, a nation of overworked, guilty housewives presented the perfect market for their new convenience foods. All the industry needed to do was to press home the message that cooking delicious meals was a housewife’s sacred duty. The bakery giant General Mills was one of the first to get in on the act, creating in 1926 the first official domestic goddess, ‘Betty Crocker’, a fictional character with her own radio show, in which she interviewed celebrity guests and dispensed domestic advice and recipes. Betty’s message was simple: a happy home was one filled with the smell of fresh baking. ‘Good things baked in the kitchen,’ she said, ‘will keep romance far longer than bright lipstick.’ The programme attracted a huge following: 40 home economists had to be employed to answer all its correspondence, amounting to hundreds of thousands of letters every year.

64

Rival food companies soon set up their own propaganda machines, with several starting their own women’s magazines filled with cookery tips laced with the same subliminal message. ‘Hitler threatens Europe,’ ran one advert in

The American Home

, ‘but Betty Haven’s boss is coming to dinner and that’s what

really

counts.’

65

Having set the entry level to domestic deity impossibly high, food companies offered mere mortals a short cut to achieving it – by using their products. Magazines brimmed with improbable recipes involving processed foods, such as one, cited by the historian Harvey Levenstein in his book

Paradox of Plenty

, that suggested mixing Campbell’s split pea soup with Ancora green turtle soup, adding sherry to the result and topping it with whipped cream.

66

Extraordinary though this concoction sounds now, it was far from unique for the time. For a couple of decades at least, the novelty of processed foods seemed to have persuaded the entire American nation to simply switch off its taste buds. The public fascination with opening cans of soup was marvellous for

food-processing companies while it lasted, but by the end of the Second World War, new convenience foods were needed to satisfy increasingly sophisticated customers. Betty Crocker cake mixtures, launched by General Mills in the late 1940s, were the result. The initial products only required water to be added to achieve a delicious ‘home-baked’ result, but the company soon realised that if housewives were asked to add an egg as well, they really felt they were baking. The egg was a ruse; a way of deceiving women into believing they were cooking properly.

By encouraging housewives to cheat, food-processing companies achieved the double whammy of raising the status of cooking, while preventing people from actually doing it. Rather than getting the satisfaction of baking a cake (which, after all, takes hardly any more effort than adding an egg and some water to a mixture of flour and cocoa powder), women were lured into paying for the privilege of pretending they had. Throughout the 1940s, the amount Americans spent on food rose steadily – the opposite of the normal trend in an era of prosperity. People were spending more on food, not because they were buying better quality, but because they were paying for the ‘added value’ of convenience. Food industry profits soared, thanks mainly to middle-class women – most of whom would have been perfectly capable – being persuaded they couldn’t cook.

By 1953,

Fortune

magazine was noting America’s ‘relentless pursuit of convenience’, in which one could ‘buy an entire turkey dinner: frozen, apportioned, packaged. Just heat and serve.’

67

Ready meals had arrived, just as family lifestyles were relaxing, allowing food processors to move out of the ‘pretend-you-cooked-it-yourself’ strand into a new leisure market. TV dinners became the new height of sophistication, eaten, for maximum effect, off specially designed plastic lap-trays. For the first time in history, food was fun, even trendy, all of which made domestic kitchens seem suddenly very out of date. In their influential 1945 book

Tomorrow’s House

, the architects George Nelson and Henry Wright argued that the galley kitchen was no longer appropriate to modern life:

Servants, as a group, are disappearing. World War One took women out of domestic occupations and put them into offices. World War

Two took a vastly greater number and put them into factories. The middle-class families and the rich, thrown more and more on their own resources, have been casting a jaundiced eye on the minimum kitchen.

68

The answer, argued the authors, was to merge kitchen and living room, replacing the ‘hospital operating-room atmosphere’ of galley kitchens with a space that was ‘pleasant to live in as well as work in … thanks to the incorporation of natural wood surfaces, bright colour, and fabrics’.

69

It was a radical vision. Never before had kitchens been admitted to polite society; now they were to become part of the furniture. Open-plan kitchens were the new must-have accessories of cutting-edge ‘contemporary’ homes: trophy cabinets brimming with gadgetry to show off to one’s friends. The ‘dream kitchen’ even became a weapon of the Cold War, when Richard Nixon tried to persuade Nikita Khrushchev of the merits of the West by showing off a mocked-up version at the 1959 Moscow Trade Fair.

With the open-plan kitchen, the humblest room in the house finally had its moment in the sun; but even in this, the kitchen’s finest hour, there were rumbles of dissent among its intended users. Most American housewives already resented having to cook. Now they were expected to do so without burning the roast, dropping peelings on the floor, looking resentful, or (worst of all) being allowed to cheat. Cooking might have come out of the closet, but as far as most women were concerned, it could go straight back in there. Before long, separate kitchens were making a comeback – this time not in order to hide the fact that people were cooking in them, but in order to hide the fact that they weren’t.

By the late 1960s, instead of burning the roast, many women had taken to burning their bras. The new politics of feminism saw cooking as the oppression of the housewife; something to ‘shackle her time, keeping her from more stimulating endeavors’.

70

It was a return to the rhetoric of a century earlier, and to the women’s movement pioneers who saw cooking as a tedious chore. After a century of rebellion and invention, women were back where they had started. In many ways, the rejection of cooking by women’s lib was more of a reaction to the

fake domestic goddess invented by food companies than it was to anything real; yet their attitude opened up new opportunities for those very companies. Refusing to cook became a badge of honour among feminists. From now on, serving up frozen pizza was not only socially acceptable; it was a positive political statement.

Postwar British housewives were just as keen as their American counterparts to cast off the shackles of culinary oppression, and the ‘relentless pursuit of convenience’ soon crossed the Atlantic. Birds Eye fish fingers and frozen peas were the first such foods to become national treasures in the 1960s, followed by Vesta curry and Cadbury’s Smash in the 1970s, M&S chilled ready meals in the 1980s, and their many imitators ever since.

71

Just as they had done on the other side of the pond, convenience foods became the national panacea, first for housewives, then for householders at large: salvation from the curse of having to cook. By 2003, the British convenience-food sector was worth £17 billion; by 2011 it is predicted to reach £33.9 billion.

72

As the ex-head of the M&S food division Clinton Silver put it, ‘Feminism owes an enormous amount to Marks & Spencer, and vice versa.’

73

One could argue that we Anglo-Saxons have been ill served by the food industry: cheated out of the more positive view of cooking that we might otherwise have developed. But if that is the case, how come other European countries have survived with their culinary traditions intact? A recent survey of European eating habits found that in Germany, the home of the Frankfurt kitchen, seven out of ten women ‘love to cook’.

74

The same was true of Spanish and Italian women, while 41 per cent of French adults were described as ‘traditional cooks who enjoy cooking’.

75

Of course there are many reasons for these cultural differences. Rural traditions have remained stronger in many parts of continental Europe than in Britain, so helping to preserve local culinary cultures: food ‘like Mother used to make’. In most parts of the Mediterranean, traditional family structures (the

sine qua non

of family meals) also survive relatively intact. Last but not least, the postwar ‘special relationship’ between Britain and America has ensured that, for better or worse, our culinary as well as our political fortunes have been inextricably linked.