Hunting Eichmann (30 page)

Authors: Neal Bascomb

The Mossad team

Zvi Aharoni

Eichmann in captivity,

wearing blacked-out goggles

Zvi Aharoni

Yosef Klein, El Al station chief

El Al / Marvin G. Goldman Collection

Zvi Tohar, El Al pilot

El Al / Marvin G. Goldman Collection

The El Al plane, Britannia 4X-AGD, used to take Eichmann out of Argentina

Peter R. Keating / Marvin G. Goldman Collection

Eichmann in Ramle

Prison, Israel, April 1961

John Milli / Government Press

Office, Israel

Eichmann in the glass booth at his trial, May 1961

Government Press Office, Israel

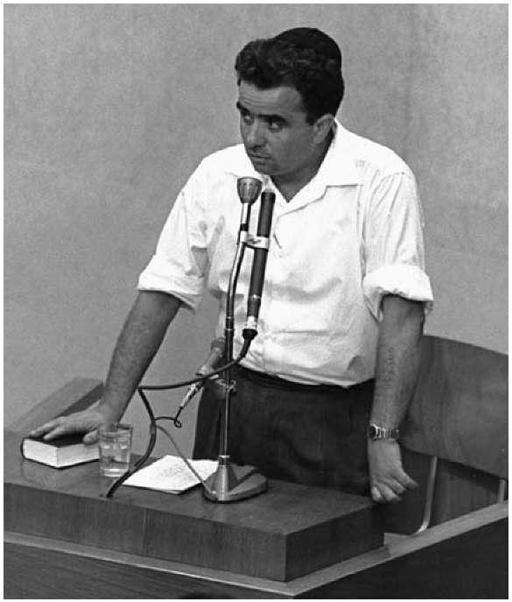

Zeev Sapir testifies at the trial, June 1961

Government Press Office, Israel

18

THE DAY AFTER

his arrival, Rafi Eitan instructed everyone to meet at Maoz. Since receiving word that the operation was going ahead, he had grown coldly determined. He knew what needed to be done, and there was no way he would allow Eichmann to elude or escape them—even if it meant taking the extreme measure of strangling him, as Moshe Tabor had earlier proposed. Now that Eitan had seen where Eichmann lived for himself, they could move forward with planning how exactly to take him.

In the living room of the Buenos Aires apartment, the agents ran through what they knew. It was clear from all their surveillance that they should capture Eichmann on his walk home. Kidnapping him from his bunker of a house introduced too many variables, including the possible actions of his wife and sons and the chance that he had a weapon. It was also unlikely that they would find a better location than an isolated stretch of road at night.

Still, there were many questions: Where between the bus stop and his house would they seize him? How would they position their cars? Would Malkin hide in the ditch beside the road and ambush him, or should they pull up alongside him in a car and grab him that way? Who would drive? What would they do if Eichmann ran? They discussed the numerous possible variations, all of them having already spent hours both alone and together on the same subject. They agreed that they should take him as soon as he turned onto Garibaldi Street, away from any passing traffic. But the question of where the cars were to be placed was a stumbling block. Eitan wanted to do some daytime surveillance with Malkin before they finalized the plan.

As for the operation's timing, they had all heard that the El Al flight was not due until May 19 and that perhaps they should postpone the capture. Eitan made it clear to everyone present that Harel had decided there would be no delay. The chief reasoned that it was better to risk holding Eichmann for longer than first planned than to let him slip through their fingers. What was more, if they scheduled the capture too close to the flight's departure, there might be unforeseeable delays (Eichmann might travel out of the city or get sick), and they would not be able to postpone the plane without setting off any alarm bells. May 10 was still the date, and it was not open for debate, despite anyone's misgivings.

The team ran through their individual responsibilities for the coming days. The strain was beginning to wear on the advance team, who had spent almost two weeks working round the clock—all the while under the stress of avoiding detection. There was still much to be done, and Eitan added one more task to the list. They were to practice grabbing and getting Eichmann into the car. Every second would count.

At Ezeiza Airport, Yosef Klein was making rapid progress on the arrangements for the El Al escape flight. Over the past few days, he had met with officials at the national airline Aerolineas Argentinas, and TransAer, a private local airline that flew Britannias. They both offered their services and outlined standard airport procedures. In his tours of the terminal, airfield, and hangars, Klein had taken care to befriend everyone from the baggage handlers, customs officers, and policemen to the service crews, maintenance workers, and staffs of both airlines. He intimated that this diplomatic flight might be a test run for regular El Al service to Argentina. When that happened, El Al would need to hire local staff. Given how little most of the airport workers were paid, the potential to earn higher wages with El Al made everyone more than helpful.

Now well acquainted with Ezeiza, Klein was certain that Eichmann could not be brought onto the plane through the terminal building, even if he were concealed in a trunk or some other contraption. There were too many customs and immigration officers, and with the heightened security from both the terrorist attacks and the anniversary celebrations, little escaped their attention. He needed to find another place to park the El Al plane that would allow the Mossad to get Eichmann on board.

When Klein visited the TransAer facilities that afternoon, he found the ideal spot. The airline's hangar was located at the edge of the airfield, where there were fewer guards. Since the airline flew Britannias, Klein could easily explain that El Al wanted to park its plane there should any spare parts or special maintenance be required. When he asked the private airline if this would be possible, it agreed.

Meanwhile, Luba Volk, who had not yet been informed of the flight's true purpose, was at the Israeli embassy with Yehuda Shimoni, completing the various letters to the Ministry of Aviation that formally requested permission for El Al to enter Argentine airspace and land at Ezeiza. She did not have an office, and she needed the help of the embassy's secretarial staff because she was not completely fluent in Spanish. Just as she was about to sign the letters, she got nervous and put down her pen. She had a premonition that if she signed her name, there would be trouble in the future.

"Maybe it would be a good idea if you signed the letter instead of me," she said, turning to Shimoni. "After all, it's a onetime flight."

"No, no. That doesn't make sense. You're the official El Al representative in Argentina," Shimoni explained. "If I sign it, they could refuse."

Volk relented and penned her name.

On the evening of May 5, behind closed doors at Maoz, Shalom Dani was forging a passport. In his left hand, he held a magnifying glass. With his steady right hand, he fashioned a typewriter-perfect letter E with a fine-tipped black pen. On the table in front of him and scattered throughout the small room were the accouterments of his craft: a multitude of colored pens and pencils, inks, dyes, small brushes, X-Acto knives, clumps of wax, a hot plate, seals, cameras, film, bottles of photographic developer, and a small store's worth of paper in every color, stock, and weight.

The forger had arrived only a few hours before, carrying with him several suitcases and boxes labeled

FRAGILE

that contained these supplies. He had buried the more suspicious items, such as the seals and some of the paper stock, among the more typical items that would correspond with the profession on his passport: artist. Dani's appearance—thin, pale, hollow-cheeked, bespectacled, and melancholic—matched the description. He had come straight to the safe house, which he suspected he probably would not leave, even to take a walk, until the operation was over. He needed to create dozens of different passports, driver's licenses, insurance cards, IDs, and other papers for the team.