I Am a Strange Loop (53 page)

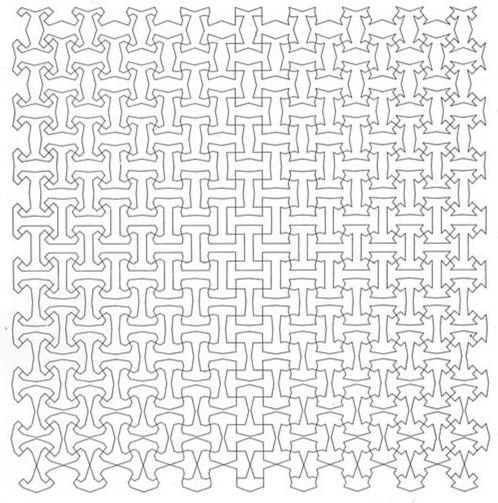

All of this suggests that each of us is a bundle of fragments of other people’s souls, simply put together in a new way. But of course not all contributors are represented equally. Those whom we love and who love us are the most strongly represented inside us, and our “I” is formed by a complex collusion of all their influences echoing down the many years. A marvelous pen-and-ink “parquet deformation” drawn in 1964 by David Oleson (below) illustrates this idea not only graphically but also via a pun, for it is entitled “I at the Center”:

Here one sees a metaphorical individual at the center, whose shape (the letter “I”) is a consequence of the shapes of all its neighbors. Their shapes, likewise, are consequences of the shapes of

their

neighbors, and so on. As one drifts out toward the periphery of the design, the shapes gradually become more and more different from each other. What a wonderful visual metaphor for how we are all determined by the people to whom we are close, especially those to whom we are closest!

How Much Can One Import of Another’s Interiority?

When we interact for a couple of minutes with a checkout clerk in a store, we obviously do not build up an elaborate representation of that person’s interior fire. The representation is so partial and fleeting that we would probably not even recognize the person a few days later. The same goes, only more so, for each of the hundreds of people we pass as we walk down a busy sidewalk at the height of the Christmas shopping madness. Though we know well that each person has at their core a strange loop somewhat like our own, the details that imbue it with its uniqueness are so inaccessible to us that that core aspect of them goes totally unrepresented. Instead, we register only superficial aspects that have nothing to do with their inner fire, with who they really are. Such cases are typical of the “truncated corridor” images that we build up in our brain for most people that we run across; we have no sense of the strange loop at their core.

Many of the well-known individuals I listed above are central to my identity, in the sense that I cannot imagine who I would be had I not encountered their ideas or deeds, but there are thousands of other famous people who merely grazed my being in small ways, sometimes gratingly, sometimes gratifyingly. These more peripheral individuals are represented in me principally by various famous achievements (whether they affected me for good or for ill) — a sound bite uttered, an equation discovered, a photo snapped, a typeface designed, a line drive snagged, a rabble roused, a refugee rescued, a plot hatched, a poem tossed off, a peace offer tendered, a cartoon sketched, a punch line concocted, or a ballad crooned.

The central ones, by contrast, are represented inside my brain by complex symbols that go well beyond the external traces they left behind; they have instilled inside me an additional glimmer of how it was to live inside their head, how it was to look out at the world through their eyes. I feel I have entered, in some cases deeply, into the hidden territory of their interiority, and they, conversely, have infiltrated mine.

And yet, for all the wonderful effects that our most beloved composers, writers, artists, and so forth have exerted on us, we are inevitably even more intimate with those people whom we know in person, have spent years with, and love. These are people about whom we care so deeply that for them to achieve some particular personal goal becomes an important internal goal for us, and we spend a good deal of time musing over how to realize that goal (and I deliberately chose the neutral phrase “that goal” because it is blurry whether it is

their

goal or

ours

).

We live inside such people, and they live inside us. To return to the metaphor of two interacting video feedback systems, someone that close to us is represented on our screen by a second infinite corridor, in addition to our own infinite corridor. We can peer all the way down — their strange loop, their personal gemma, is incorporated inside us. And yet, to reiterate the metaphor, since our camera and our screen are grainy, we cannot have as deep or as accurate a representation of people beloved to us as either our own self-representation or their own self-representation.

Double-clicking on the Icon for a Loved One’s Soul

There was a point in my 1994 email broodings to Dan Dennett where I worried about how it would feel when, for the first time after her death, I would watch a video of Carol. I imagined the Carol symbol in my head being powerfully activated by the images on tape — more powerfully activated than at any moment since she had died — and I was fearful of the power of the illusion it would create. I would seem to see her standing by the staircase, and yet, obviously, if I were to get up and walk through the house to the spot where she had once stood, I would find no body there. Though I would see her bright face and hear her laugh, I could not go up to her and put my arm around her shoulders. Watching the tapes would heighten the anguish of her death, by

seeming

to bring her back physically but doing nothing of the sort in reality. Her physical nature would not be brought back by the tapes.

But what about her

inner

nature? When Carol was alive, her presence routinely triggered certain symbols in my brain. Quite obviously, the videos would trigger those same symbols again, although in fewer ways. What would be the nature of the symbolic dance thus activated in my brain? When the videos inevitably double-clicked on my “Carol” icon, what would happen inside me? The strange and complex thing that would come rushing up from the dormant murk would be a real thing — or at any rate, just as real as the “I” inside me is real. The key question then is, how different is that strange thing in my brain from the “I” that had once flourished inside Carol’s brain? Is it a thing of an entirely different type, or is it of the same type, just less elaborate?

Thinking with Another’s Brain

Of all Dan Dennett’s many reactions to my grapplings in that searing spring of 1994, there was one sentence that always stood out in my mind: “It is clear from what you say that Carol will be thinking with your brain for quite some time to come.” I appreciated and resonated to this evocative phrase, which, as I later discovered, Dan was quoting with a bit of license from our mutual friend Marvin Minsky, the artificial-intelligence pioneer — copycats everywhere!

“She’ll be thinking with your brain.” What this Dennett–Minsky utterance meant to me was roughly the following. Input signals coming to me would, under certain circumstances, follow pathways in my brain that led not to

my

memories but to

Carol’s

memories (or rather, to my low-resolution, coarse-grained “copies” of them). The faces of our children, the voices of her parents and sisters and brothers, the rooms in our house — such things would at times be processed in a frame of reference that would imbue them with a Carol-style meaning, placing them in a frame that would root them in and relate them to

her

experiences (once again, as crudely rendered in my brain). The semantics that would accrue to the signals impingent on me would have originated in her life. To the extent, then, that I, over our years of living together, had accurately imported and transplanted the experiences that had rooted Carol on this earth, she would be able to react to the world, to live on in me. To that extent, and only to that extent, Carol would be thinking with my brain, feeling with my heart, living in my soul.

Mosaics of Different Grain Size

Since everything hung on those words “to the extent that X”, what seemed to matter most of all here was

degree of fidelity

to the original, an idea for which I soon found a metaphor based on portraits rendered as mosaics made out of small colored stones. The more intimately someone comes to know you, the finer-grained will be the “portrait” of you inside their head. The highest-resolution portrait of you is of course your own self-portrait — your own mosaic of yourself, your self-symbol, built up over your entire life, exquisitely fine-grained. Thus in Carol’s case, her own self-symbol was by far the finest-grained portrait of her inner essence, her inner light, her personal gemma. But surely among the next-highest in resolution was

my

mosaic of Carol, the coarser-grained copy of her interiority that resided inside my head.

It goes without saying that my portrait of Carol was of a coarser grain than her own; how could it not be? I didn’t grow up in her family, didn’t attend her schools, didn’t live through her childhood or adolescence. And yet, over our many years together, through thousands of hours of casual and intimate conversations, I had imported lower-resolution copies of so many of the experiences central to her identity. Carol’s memories of her youth — her parents, her brothers and sisters, her childhood collie Barney, the family’s “educational outings” to Gettysburg and to museums in Washington D.C., their summer vacations in a cabin on a lake in central Michigan, her adolescent delight in wildly colorful socks, her preadolescent loves of reading and of classical music, her feelings of differentness and isolation from so many kids her age — all these had imprinted my brain with copies of themselves, blurry copies but copies nonetheless. Some of her memories were so vivid that they had become my own, as if I had lived through those days. Some skeptics might dismiss this outright, saying, “Just pseudo-memories!” I would reply, “What’s the difference?”

A friend of mine once told me about a scenic trip he had taken, describing it in such vivid detail that a few years later I thought I had been on that trip myself. To add insult to injury, I didn’t even remember my friend as having had anything to do with “my” trip! One day this trip came up in a conversation, and of course we both insisted that

we

were the one who had taken it. It was quite puzzling! However, after my friend showed me his photos of the trip and recounted far more details of it than I could, I realized my mistake — but who knows how many other times this kind of confusion has occurred in my mind without being corrected, leaving pseudo-memories as integral elements of my self-image?

In the end, what is the difference between actual, personal memories and pseudo-memories? Very little. I recall certain episodes from the novel

Catcher in the Rye

or the movie

David and Lisa

as if they had happened to me — and if they didn’t, so what? They are as clear as if they had. The same can be said of many episodes from other works of art. They are parts of my emotional library, stored in dormancy, waiting for the appropriate trigger to come along and snap them to life, just as my “genuine” memories are waiting. There is no absolute and fundamental distinction between what I recall from having lived through it myself and what I recall from others’ tales. And as time passes and the sharpness of one’s memories (and pseudo-memories) fades, the distinction grows ever blurrier.

Transplantation of Patterns

Even if most readers agree with much that I am saying, perhaps the hardest thing for many of them to understand is how I could believe that the activation of a symbol inside my head, no matter how intricate that symbol might be, could capture any of someone else’s

first-person

experience of the world, someone else’s consciousness. What craziness could ever have led me to suspect that someone

else’s

self — my father’s, my wife’s — could experience feelings, given that it was all taking place courtesy of the neurological hardware inside

my

head, and given that every single cell in the brain of the other person had long since gone the way of all flesh?

The key question is thus very simple and very stark: Does the actual hardware matter? Did only

Carol’s

cells, now all recycled into the vast impersonal ecosystem of our planet, have the potential to support what I could call “Carol feelings” (as if feelings were stamped with a brand that identified them uniquely), or could

other

cells, even inside me, do that job?