I Can Barely Take Care of Myself (8 page)

Read I Can Barely Take Care of Myself Online

Authors: Jen Kirkman

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Women, #Personal Memoirs, #Humor, #Topic, #Marriage & Family

From then on I could panic on airplanes even if the view was fantastic, even if there was no turbulence, even if the flight attendants were actually smiling that day, even if the pilot said, “This is God. I will be your pilot today and I swear to myself—we will not crash.” I could panic even

sitting in first class, where they serve warm cookies and champagne. Distractions and logic do not help temper what my psychiatrist explains to me is just some overintense fight-or-flight response that is left over from my caveman DNA. I have nowhere to put my adrenaline on flights, since my inner caveperson cannot club the wild beast that is chasing her and drag it back triumphantly to the cave.

There is not enough legroom for that.

After ten years of school-vacation trips to Disney World, at age sixteen I finally called it quits. And it wasn’t because I was too cool. I loved Disney World. By the time I was fourteen, I had started to wear all black to the Magic Kingdom and I posed with Mickey wearing a mean scowl, but I secretly wanted to be there while looking like I didn’t. I had to

surrender my annual trip to the most magical place on earth—or anywhere else that required flight—because my anxiety on airplanes had grown too severe. I couldn’t look forward to seeing a palm tree if it meant I had to survive a few hours of sheer terror to get to it.

Not flying for a while didn’t cramp my high school life at all. I was happy just staying on the ground and being a teenager in

the suburbs of Massachusetts. I went to college in Boston. No planes needed. My goal was to become a famous world-traveling actress who lived on the West Coast. I figured I’d eventually just grow out of my fear of flying in the same way that I had grown out of thinking it looked really defiant to wear floral dresses with black knee-high combat boots.

I sat out spending a semester abroad in Amsterdam

during my junior year of college simply because I was too afraid to cross the pond at thirty thousand feet. I watched classmates and friends pack up their backpacks. I stood with them as they convened in the dormitory lobby, waiting for the shuttle that would whisk them to the airport. They would board a plane without worrying about meeting an untimely death. And they would spend three months

in Amsterdam living in a converted castle and studying things like Shakespearean Breath Control for Actors. I stayed behind with other nonadventurous people and we suffered through another New England winter, during which my greenskeeper dad would drive his sitting snowplow throughout the golf course and yell at the kids sledding, “Hey, there’s grass under there and you’re ruining it!”

In retrospect,

I’m okay with my decision to remain in Boston while some of my friends lived in the Netherlands. I’m glad I didn’t turn into my friend Shane. Shane and I had coffee upon his return and he lit up a marijuana cigarette in the middle of our local café. I grabbed his arm. “Are you crazy?” Shane looked at me, puzzled. “Dude, what?” I grabbed his joint and put it out. “Ohhhh. Yeah. It’s against

the law. I forgot. Man, I’m just so used to being in a more culturally mature place like Amsterdam where pot is legal.”

When I was twenty and living with my parents for the summer before my senior year of college, I decided that I couldn’t be afraid to go anywhere anymore. In case I

didn’t

naturally outgrow my fear, I didn’t want to be stuck in Boston for the rest of my life. So I joined a support

group at Boston’s Logan Airport in the Delta Airlines

terminal. The group was called—and I’m not joking—Logan’s Heroes. My fearless leader was Dr. Al Forgione, a clinical psychologist who in twelve weeks was going to rewire our brains so that we associated thoughts of flying with relaxation rather than catastrophe.

Dr. Al handed me a small cup of orange juice and told me to take a seat anywhere

at the conference table. At my chair I found a book and a collection of cassette tapes called

Relaxation Exercises for Air Travel.

Dr. Al said, “Flip through the book if you want, but don’t look at the pictures on page sixty-eight. You won’t be ready for that until week six.” I immediately disobeyed the doctor’s orders and turned to page 68, where I came face-to-face with a photo of a plane’s

cockpit. My heart went from zero to high blood pressure and I felt the classic prelude to a panic attack. I couldn’t even look at a

picture

of a plane? Shit. I didn’t know I had it that bad.

At one point Dr. Al said to me, “What are you doing here? You’re too young to have any fears! These years are the best years of your life!”

In my opinion, sitting in an airport with a bunch of terrified

middle-age people on a balmy night the summer before one’s senior year in college was not anyone’s idea of “the best years of your life.” I had never considered that I was too young to have fears. I knew that being too afraid to travel abroad put me in the minority at college. But I had expected to come to Logan’s Heroes and meet all the other twenty-year-olds who weren’t spending a semester abroad

finding themselves.

“Get mad at the fear!” This was Dr. Al’s motto. Take the rush of adrenaline that fear produces and turn it outward. Screw that fear! How dare that fear creep into our heads and start messing with us. We were in control! The fear was an unwelcome pest. It all sounded empowering in the moment and especially sitting in the safety of a conference room chock full of gravity.

Being a Logan’s Hero was hard work. Every week I had to read a page of the

Fearless Flying

book. Every night I was to sit and do a guided meditation. This was called “practicing the relaxation

response.” Dr. Al was the narrator on the tape. He suggested getting in a comfortable chair and picturing yourself alone on a beach in a quiet, remote location. That’s the first time that I realized I also

had a fear of being on a beach in a remote location. Was there a hospital in this beach town? How alone was I? What did I eat? Was there shelter in case of a hurricane? I decided that it was best for me to picture myself on a crowded beach, complete with all of the necessary accommodations.

All of us Logan’s Heroes took a graduation flight from Boston to New York City and back. Every other Logan’s

Hero was heroic. They did not panic and used only breathing techniques, no drugs or alcohol, to combat their anxiety on the flight. I didn’t use drugs or alcohol either but I couldn’t breathe. I white-knuckled the flight and sat next to Dr. Al, making whimpering sounds. When the plane landed, he took me aside and said, “I think there is more going on with you than just a fear of flying. You

might want to look into seeing a psychiatrist who can help you with your anxiety. And just remember, this is the time of your life.”

Dr. Al was right. I did need a psychiatrist. I finally started seeing one a few years later once the mere fear of having a panic attack caused actual panic attacks in malls, on highways—even while lying quietly in “corpse pose” in yoga class. All that silence and

stillness and my brain would start to go crazy:

Hey, Jen, while you have five minutes at the end of class, I thought I’d remind you that you’re just a small person stuck on a ball that is spinning through the atmosphere.

My psychiatrist offered me something that Dr. Al never did. Just like Dr. Al had his motto: “Get mad at the fear!” I now have my own motto: “Have Klonopin, will travel.”

It

took a lot of therapy and a lot of different antidepressants to rewire my brain. I’m still in therapy but am not medicated—unless you count Skittles. I take Klonopin as needed when I fly and I carry some in my purse just in case. (Please, muggers, if you see me on the street, don’t hit me over the head and steal my purse. Psychiatrists never believe you when you say your prescription was stolen.)

I finally understand that it’s okay to be a little afraid of things but that obsessing over them does not mean you have any more control over what you fear. There’s a big difference between thinking,

Hey, it would suck to die in a nuclear war or a plane crash,

and,

Good morning—oh my God. What if a nuclear bomb hits my home now? Okay, what about

now? Now?

When I turned thirty-five, I finally

shook off most of the “fear of life” that had gripped me since before MTV was even a thing.

The Day After

, my parents, and Eastern Airlines are not to blame for the neuroses of my youth. Clearly, other children watched that movie but were comforted by Sting’s end credits song, “Russians.”

I just happened to be wired to develop panic disorder, depression, and anxiety. Youth was wasted on the young

in my case—but I am not going to waste my middle age. In the past two years I’ve been lucky enough to have my work take me to London, Australia, and almost every state in America. It’s afforded me vacations in Paris, Mexico, and Hawaii. There are so many more places I want to see. I’ve relinquished my responsibilities as the world’s sole nuclear war worrywart, and the only child I want to indulge

right now is my inner one.

A LOT OF my friends who have kids say to me, “We’d love to travel more and go out every night, but we have a child now. We got that out of our system in our twenties, so now it’s just time to settle down.” Well, I got nothing out of my system in my twenties and I’m excited about starting to put things in my system. I’m lucky that my friend Sarah doesn’t want kids either,

and if she ever changes her mind, I’m going to push her down a flight of stairs.

Sarah and I decided to take a trip to Maui together to ring in the 2012 New Year. We figured after we spent Christmas with our respective families, we’d then detox in Hawaii by cooking our skin in the sun and getting salty seawater in our eyes. We both write for

Chelsea Lately

as well as work on other projects, and

we travel a lot to do

stand-up. We wanted a vacation where we could do absolutely nothing. (For parents who are reading this, “nothing” is that thing you will get to do once your kids leave for college, if they ever leave for college. I hear tuition is skyrocketing.)

We opted to stay at the Grand Wailea Maui. It’s a family-friendly resort. We’re not opposed to families existing—we’re very generous

that way. Sarah and I were confident that we’d be undisturbed by screaming toddlers in the cabana we rented at the adults-only pool.

See? There was even a sign at the entrance of the adult pool that clearly states as much. I don’t know anyone who dutifully and without question obeyed authority more than my parents and I when I was a child. That sign would have put the fear of God in us. If eight-year-old Jen had even walked

near

this sign on a family vacation, my

mother would have grabbed my arm and harshly whispered, “Jennifah,

don’t go near there, it’s for rich people who will have their own private security. They’ll have us arrested and we’ll have to spend the rest of the vacation in the town jail run by the local mafia.”

Seems like kids these days (and their parents) aren’t scared of some words engraved on a placard. On our first day in Maui, there was not one adult in the adult pool because there were so many kids

swimming (aka peeing) in the four-foot-deep waters. There were tween boys in the hot tub! Just in case you think I’m not being fair, just in case you’re thinking to yourself,

Jen, let the children enjoy a refreshing chlorine dip in the hot Maui sun! They’re on vacation and they’re just kids. This is the time of their lives!

I’ll show you Exhibit A (and the only exhibit that I have to offer): On

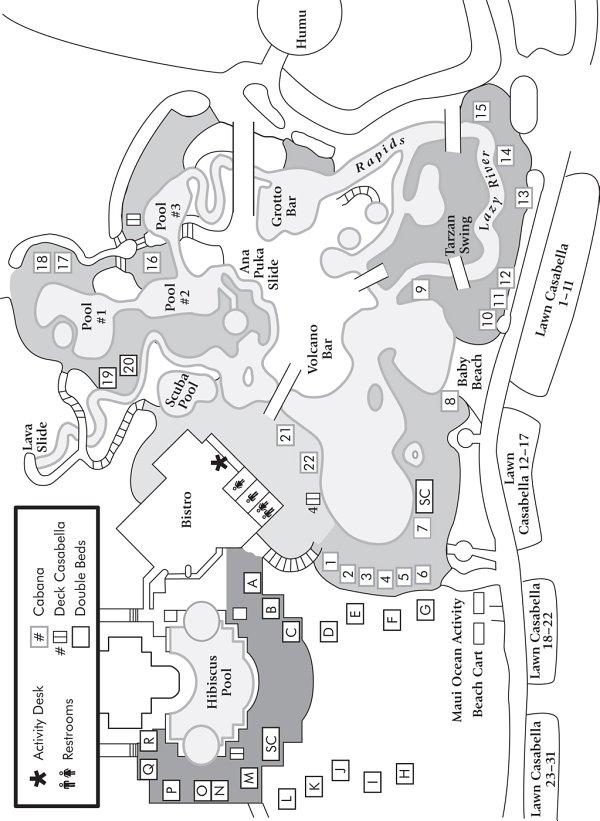

the next page is a map of the pools at the Grand Wailea hotel in Maui:

The only pool for people eighteen and over is the Hibiscus Pool. Children have access to a lazy river, rapids, a water slide, a scuba pool, Pool no. 1, Pool no. 2, Pool no. 3, and even a pool with a swim-up bar for their twenty-one-and-over parents! There was no swim-up bar at the Hibiscus Pool. There was no bar at all. Just

a few harried waitresses trying to deliver watered-down drinks while rogue toddlers tripped them up.

My legs were sore from being cramped on a long flight and because I’m thirty-eight now and beginning to feel the fact that I’m slowly rotting from the inside. I wanted to sit in the hot tub but I couldn’t because I was self-conscious about sitting in a hot tub with a bunch of twelve-year-old boys

who would see me in my bikini. If I wanted to spend my vacation feeling uncomfortable in a bathing suit around boys, I’d buy a round-trip ticket on a time machine and go back to 1987, when I was called “boobless” by two boys back on Duxbury Beach in Massachusetts. Sure, I have boobs now, but I also have a stomach. There was probably a six-month window of time when I was nineteen when my boobs

were of a good size and I had no stomach flab—that girl would look great in a bikini if she weren’t busy trying to be “grunge” in her oversize flannel shirts.