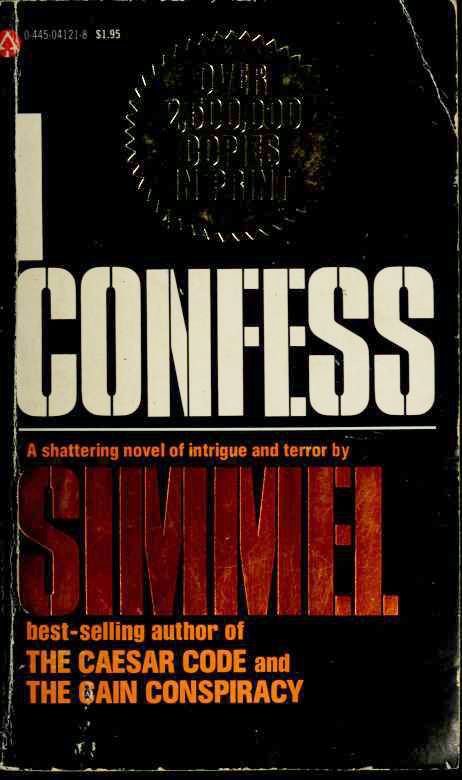

I Confess

Authors: Johannes Mario Simmel

"Knowledge is free to those who seek it"

Digitized by the Internet Archive. Cracked and Scrubbed by Fynn (aka Tashfin) in 2014.

BOOK ONE

\

My name is Walter Frank.

I was born in Vienna on May 17, 1906. I am an Austrian citizen, Roman Catholic, married to Valery Frank, nee Kesten. I am an exporter, residing at Reisnerstrasse 112, Vienna III, and what I am about to write is the story of a mistake.

I have given a lot of thought to the question: is "mistake" the best word I can find to convey the events of the last months? Does it cover a conscientious accounting as well as the quintessence of the adventure that now hes almost completely behind me? Isn't it perhaps a too pretentious world? Have I the right to use it in my case? I have thought it over carefully, without skipping or forgetting anything, and have come to the conclusion—"mistake" is the right word.

It was the greatest mistake of my life and it wiH be the last because I am ill and will soon die. My illness is not unpleasant if you can look away from the fact that it is fatal. Even in its advanced stage, in which I now find myself, the symptoms are bearable. I do have to take strong medication to combat the pain: morphine-hydrochloride, but when I take it I am free of pain. I take good care of myself, and when I notice the pressure at the root of my nose increasing, signaling that familiar pulsation behind the eyes, I give myself the injection. That's all there is to it. As I just said, it is not an unpleasant illness if one forgets the fact that it is lethal.

To be quite truthful, there are other symptoms—dizziness, for instance, due to certain prolapses in the brain and the disproportionate detrition of various muscles. My eyes, too, tire easily, and I shall therefore write my story only a httle at a time. I shall have to interrupt my work frequently, and I think the best procedure will be to number each section as I go along, not only to simplify the reading of these pages for Dr. Freund, but also to have a record of how much I have managed to produce daily. Because I have to be very sensible and economical with my time if I am to reach the end before I die. And I want to reach the end. It's the only thing I still really want—to see the story of this mistake to its written conclusion.

I have just read these opening lines again and find that I have already forgotten something and glossed over something; in fact, in these first lines I have already lied. And there is no point in continuing until I have put things straight. I therefore withdraw what I have just stated.

My name is not Walter Frank. I was not bom on May 17, 1906, in Vienna. I am not an Austrian citizen, Roman CathoUc, married to Valery Frank, nee Kesten, nor am I an exporter. All the above is not true. The truth is:

My name is James Elroy Chandler.

I was bom on April 21, 1911 in New York City. T am an American citizen, Protestant, married to Margaret Chandler, nee Davis. And my profession is—or I should say, was—script writer in Hollywood,

It IS snowing.

From my window I can see the flakes sinking soundlessly to the ground. The twilight in my room is soothing to my eyes and head. Dr. Freund was so kind as to assign me this room. It is situated in the garden-wing of the large, modem school where he works. A play area, surrounded by tall old trees, lies under my window. In good weather, the high-pitched voices of children playing rise up to me. I hsten to their laughter and their breathless little cries. Today the play area is deserted. The snow falls soundlessly.

I am seated in a comfortable armchair, the paper T am writing on lies on my knees. Dr. Freund just came by to ask how I was feeling. He was pleased when I told him I had started to write my story. The idea to write it was his. AU my more recent plans have originated with him. Since I met him I have accepted his leadership and advice more and more, and ever since I began to feel uneasy in my apartment in the Reisnerstrasse and more or less moved in on him, I do exclusively what he thinks is right and tells me to do. I have confidence in him. He is kind, wise and knows all about me. I am very happy to have met him while there was still time.

When I came to him and told him my story, and when he found out how things stood with me, he advised me to write it all down. He felt this would relieve me. The success of his educational method rests, as do all such methods, in that he first lets his patients—and I have become one of them—tell what oppresses and what fulfills

them, thereby granting them a sense of release. I grasped this at once when he suggested it to me for the first time.

"You mean," I said, "that a criminal feels impelled to boast of his crime or to reproach himself for what he has done?"

He shook his head.

'This urge," he said, "to talk about things that move us deeply is felt by criminals and saints. Not only Dr. Crip-pin was drawn back to the scene of his crime; the Apostles John and Luke felt impelled to write their gospels."

"I am not a saint."

"Certainly not," he said, "but you are a writer. You always wanted to write a book, didn't you? And you never did. So write it now. It's your last chance."

Yes. It is my last chance.

There were many occasions when I could have written a book, but I didn't grasp the opportunity; I have written scripts, none of them good. If they had been good—they, and the films made of them—it would have compensated for any books I may have wanted to write. But they were not good and therefore not an adequate substitute. I missed my chances, missed them up to this final one which offers itself to me here in this still, twiht room so shortly before my death. I must make use of it; I intend to make use of it. I want to tell my story.

Suddenly, however, just because it is my story, I am overwhelmed by doubt. Until now, the only thing I have written was fiction, stories I thought up and constructed for their effect, by starting at the end and working my way back to the beginning, but now I face merciless reality, cold, pitiless, relentless facts, and a progressive development of which I know the beginning but not the end.

The beginning!

Where do I begin? Do I know when my story started, at what point it would be right to start telling it? Did it begin on the evening I landed at the Munich airport? Or on the night T met Yolanda in a villa on the outskirts of that city? Did it begin in the Golden Cross Hospital? Or

earlier? Or later? Didn't it perhaps not start in Germany at all but before that, in Hollywood? Isn't my story after all nothing but an endless sequence of events that form a chain reaching back all the way to the day I was bom? And mustn't I therefore set a time arbitrarily, out of this progression, and declare—^this is where it all began?

I feel this is what I shall have to do. And I think I have found my starting point. It began five months ago, keeping in mind that we now write January 4. It was a dismal Sunday, raining outside, and when I woke up, the light was falling dimly into the room in which I found myself. It was on the second floor of 127 Romanstrasse, in Munich. The walls of the building were covered with vines. Outside, on the silent street, there were trees. The rain drunmied down on them, and the first thing I saw as I opened my eyes was the dark green leaves of the chestnut tree in front of the window, drooping with rain. Yes, they were the first thing I saw. I can remember it exactly, and that all this lies back five months, that everything started five months ago on a rainy Sunday afternoon....

I had a headache when I woke up, an ordinary headache, something I always have on awakening, only today it was accompanied by a distressing nausea, the result of an excess of alcohol the night before. I had drunk too much and it hadn't agreed with me. I groaned, sat up, reached for my wristwatch lying on the bedside table. It was ten to four.

Yolanda was still asleep.

She lay beside me, on her left side, and her red hair

was sprawled wildly across the pillow which she was clutching in her arms. I looked at her. She used a bright red lipstick and it had smeared, forming bright red spots on the very white skin of her face. She was breathing deeply. Her naked breast rose and fell regularly. Yolanda always slept naked and always uncovered herself when she slept. I pulled the blanket over her and got up. My head ached excruciatingly; I looked for my pills but couldn't find them. The room was in a state of wild disorder—Yolanda's clothes all over the floor, mine on an armchair, and now I saw that we had forgotten to turn off the radio. It was humming softly and the light was on. We had been listening to dance music on shortwave; the station wasn't broadcasting now.

I turned off the radio and looked for my pills in my suit. I was irritated, and my movements betrayed a certain hysterical aimlessness, as they did usually when I had had too much to drink. I didn't find them in my suit. I went into the bathroom; they weren't there either. I turned on the water in the tub and went back into the bedroom. Yolanda was still asleep. She had uncovered herself again and was lying on her stomach. Her long legs dangled over the edge of the bed. She was talking in her sleep.

"That doesn't prove a thing," she said and laughed. "Not a thing." She spoke a few words I didn't catch, then, clearly, "You can't come to me with accusations like that."

I paid no attention to her. She often talked in her sleep, always senseless babbling. At the beginning, when I didn't trust her and was jealous, I'd wake her up and question her. She'd give me the craziest answers and I would be beside myself with rage, until the day she told a story about me. Pure fiction! That was the end of my interest in her nightly confessions.

I came to my senses abruptly—I must have been over the hills and far away for quite some time—and found myself sitting on the edge of the bed, staring at Yolanda's smooth white back. I had evidently fallen asleep with my

eyes open. It was four thirty. That happened to me frequently lately. Awake, I would experience lapses of consciousness, especially when I had been drinking the night before. Then it could happen that, when I got up next morning, I would put on one shoe, and half an hour later find myself in the same position, staring into space, the other shoe still in my raised hand.

I rubbed my forehead and thought hard—^what had I come back into the bedroom for? Then I remembered and in the next moment saw the pills. They were lying beside my wristwatch, on the bedside table, a glass of water next to them. I had put everything out meticulously before going to bed. Evidently I had not got around to taking the pills. A serious omission. I always took the pills at night, in order to have a clear head in the morning for my work. The thought of the work-free Sunday that lay ahead must have made me careless. I made up for it now. The water tasted like cod liver oil and my tongue felt like an emery board. Then I thought of the tub and ran back to the bathroom. It was about to overflow. I turned off the water, took off my pajamas and got into the hot water.

At first I felt dreadfully nauseated. My temples were pulsating madly, the sweat stood in beads on my forehead. I could hardly breathe, but I stuck it out. I was used to this. In ten minutes I would feel fine. I leaned back and closed my eyes, but the headache did not go away. I saw the fine red veins on the inside of my Uds rotating, the way they did lately, and I thought of Margaret.

She had gone to Chiemsee, to visit some American friends who were spending the summer on the lake. She had met them quite by chance in Munich. I had promised to pick her up Sunday evening. She had already been there four days. The motion picture company for which I was working had put a small car at my disposal. I could be in Chiemsee in two hours. It was four-thirty. I had awakened just in time.

The nausea left me, the headache remained. I washed my face with cold water for quite some time. It didn't

help. The rain was beating on the tin roof in front of the bathroom window, otherwise it was still; only now and then the footfall of a pedestrian in the street below. I dried myself. The headache persisted. I thought of the two-hour drive ahead of me with mixed feelings, and with even more trepidation of Margaret and her friends. We would probably have to stay for dinner. Margaret would talk big about my work and I would be bored. In the end we would quarrel over something unimportant and she would weep. It was all so distasteful and so inevitable. It was the way it always had been.

I went back to the bedroom. I had to call Hellweg. Hellweg was the writer who was working on the German version of our script. I was writing the English one. I wanted to ask him to come to see me at the hotel next morning. I couldn't write in the company office anymore. Too many people. They made me nervous. Perhaps Hellweg and I could get out of the city. He was a decent fellow. I wouldn't have minded being alone with him for a while. Alone with a man. Lately women had been making me nervous. More nervous than usual. Not only Margaret. Yolanda too. All women. I was overworked. My first draft was ready. All we had to do was synchronize our two versions. But I was having trouble with the dialogue. I always had trouble with dialogue. Goddammit, my head!

I went over to the mirror to tie my tie. It was a large mirror, suitable for a woman's needs. In front of it—a vanity table, in front of that a red velvet hassock. The room was modern, practical and feminine. It smelled of lavender and wax. It took me longer than usual to tie my tie and I swore softly. My fingers were trembhng, and I couldn't seem to get them to go where I wanted them to go. Overworked. Too much liquor. Too many cigarettes. I thought longingly of the day when my work would be done and I could leave Munich. I hadn't felt right in Munich. Perhaps I'd go to the Riviera. I could afford it.

I looked up and saw that Yolanda was awake. She was lying on her back, her long legs crossed, her light green

eyes watching me thoughtfully. I had the uncomfortable feeling that she had been watching me for some time.

"Hello," I said.

"Hello," said Yolanda.

"How are you?"

"Fine." She lifted her arms above her head and yawned, twisting her body Hke a lazy cat. Then she sat up and scratched her back by rubbing it against the headboard. She drew her legs up to her body and blew the hair off her forehead. "And you?"

"I have a splitting headache." At last my tie looked right.