I Have Landed (19 page)

Authors: Stephen Jay Gould

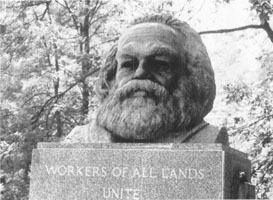

But one monument in Highgate Cemetery might seem conspicuously out of place, to people who have forgotten an odd fact from their high-school course in European history. The grave of Karl Marx stands almost adjacent to the tomb of his rival and arch opponent of all state intervention (even for street lighting and sewage systems), Herbert Spencer. The apparent anomaly only becomes exacerbated by the maximal height of Marx's monument, capped by an outsized bust. (Marx had originally been buried in an inconspicuous spot adorned by a humble marker, but visitors complained that they could not find the site, so in 1954, with funds raised by the British Communist Party, Marx's gravesite reached higher and more conspicuous ground. To highlight the anomaly of his presence, this monument, until the past few years at least, attracted a constant stream of the most dour, identically suited groups of Russian or Chinese pilgrims, all snapping their cameras, or laying their “fraternal” wreaths.)

Marx's monument may be out of scale, but his presence could not be more appropriate. Marx lived most of his life in London, following exile from Belgium, Germany, and France for his activity in the revolution of 1848 (and for general political troublemaking: he and Engels had just published the

Communist Manifesto)

. Marx arrived in London in August 1848, at age thirty-one, and lived there until his death in 1883. He wrote all his mature works as an expatriate in England; and the great (and free) library of the British Museum served as his research base for

Das Kapital

.

Let me now introduce another anomaly, not so easily resolved this time, about the death of Karl Marx in London. This item, in fact, ranks as my all-time-favorite, niggling little incongruity from the history of my profession of evolutionary biology. I have been living with this bothersome fact for twenty-five years, and I made a pledge to myself long ago that I would try to discover some resolution before ending this series of essays. Let us, then, return to Highgate Cemetery, and to Karl Marx's burial on March 17, 1883.

Friedrich Engels, Marx's lifelong friend and collaborator (also his financial “angel,” thanks to a family textile business in Manchester), reported the short, small, and modest proceedings (see Philip S. Foner, ed.,

Karl Marx Remembered: Comments at the Time of His Death

[San Francisco: Synthesis Publications, 1983]). Engels himself gave a brief speech in English that included the following widely quoted comment: “Just as Darwin discovered the law of evolution in organic nature, so Marx discovered the law of evolution in human history.” Contemporary reports vary somewhat, but the most generous count places only nine mourners at the gravesiteâa disconnect between immediate notice and later influence exceeded, perhaps, only by Mozart's burial in a pauper's grave.

(I exclude, of course, famous men like Bruno and Lavoisier, executed by state power and therefore officially denied any funerary rite.)

The list, not even a minyan in length, makes sense (with one exception): Marx's wife and daughter (another daughter had died recently, thus increasing Marx's depression and probably hastening his end); his two French socialist sons-in-law, Charles Longuet and Paul Lafargue; and four nonrelatives with long-standing ties to Marx, and impeccable socialist and activist credentials: Wilhelm Liebknecht, a founder and leader of the German Social-Democratic Party (who gave a rousing speech in German, which, together with Engels's English oration, a short statement in French by Longuet, and the reading of two telegrams from workers' parties in France and Spain, constituted the entire program of the burial); Friedrich Lessner, sentenced to three years in prison at the Cologne Communist trial of 1852; G. Lochner, described by Engels as “an old member of the Communist League”; and Carl Schorlemmer, a professor of chemistry in Manchester, but also an old communist associate of Marx and Engels, and a fighter at Baden in the last uprising of the 1848 revolution.

But the ninth and last mourner seems to fit about as well as that proverbial snowball in hell or that square peg trying to squeeze into a round hole: E. Ray Lankester (1847â1929), already a prominent young British evolutionary biologist and leading disciple of Darwin, but later to becomeâas Professor Sir E. Ray Lankester K.C.B. (Knight, Order of the Bath), M.A. (the “earned” degree of Oxford or Cambridge), D.Sc. (a later honorary degree as doctor of science), F.R.S. (Fellow of the Royal Society, the leading honorary academy of British science)âjust about the most celebrated, and the stuffiest, of conventional and socially prominent British scientists. Lankester moved up the academic ladder from exemplary beginnings to a maximally prominent finale, serving as professor of zoology at University College London, then as Fullerian Professor of Physiology at the Royal Institution, and finally as Linacre Professor of Comparative Anatomy at Oxford University. Lankester then capped his career by serving as director (from 1898 to 1907) of the British Museum (Natural History), the most powerful and prestigious post in his field. Why, in heaven's name, was this exemplar of British respectability, this basically conservative scientist's scientist, hanging out with a group of old (and mostly German) communists at the funeral of a man described by Engels, in his graveside oration, as “the best hated and most calumniated man of his times”?

Even Engels seemed to sense the anomaly, when he ended his official report of the funeral, published in

Der Sozialdemokrat

of Zurich on March 22, 1883, by writing: “The natural sciences were represented by two celebrities of the first rank, the zoology Professor Ray Lankester and the chemistry Professor

Schorlemmer, both members of the Royal Society of London.” Yes, but Schorlemmer was a countryman, a lifelong associate, and a political ally. Lankester did not meet Marx until 1880, and could not, by any stretch of imagination, be called a political supporter, or even a sympathizer (beyond a very general, shared belief in human improvement through education and social progress). As I shall discuss in detail later in this essay, Marx first sought Lankester's advice in recommending a doctor for his ailing wife and daughter, and later for himself. This professional connection evidently developed into a firm friendship. But what could have drawn these maximally disparate people together?

We certainly cannot seek the primary cause for warm sympathy in any radical cast to Lankester's biological work that might have matched the tenor of Marx's efforts in political science. Lankester may rank as the best evolutionary morphologist in the first generation that worked through the implications of Darwin's epochal discovery. T. H. Huxley became Lankester's guide and mentor, while Darwin certainly thought well of his research, writing to Lankester (then a young man of twenty-five) on April 15, 1872: “What grand work you did at Naples! [at the marine research station]. I can clearly see that you will some day become our first star in Natural History.” But Lankester's studies now read as little more than an exemplification and application of Darwin's insights to several specific groups of organismsâa “filling in” that often follows a great theoretical advance, and that seems, in retrospect, not overly blessed with originality.

As his most enduring contribution, Lankester proved that the ecologically diverse spiders, scorpions, and horseshoe crabs form a coherent evolutionary group, now called the Chelicerata, within the arthropod phylum. Lankester's

research ranged widely from protozoans to mammals. He systematized the terminology and evolutionary understanding of embryology, and he wrote an important paper on “degeneration,” showing that Darwin's mechanism of natural selection led only to local adaptation, not to general progress, and that such immediate improvement will often be gained (in many parasites, for example) by morphological simplification and loss of organs.

Karl Marx's grave site in Highgate Cemetery, London

In a fair and generous spirit, one might say that Lankester experienced the misfortune of residing in an “in between” generation that had imbibed Darwin's insights for reformulating biology, but did not yet possess the primary toolâan understanding of the mechanism of inheritanceâso vitally needed for the next great theoretical step. But then, people make their own opportunities, and Lankester, already in his grumpily conservative maturity, professed little use for Mendel's insights upon their rediscovery at the outset of the twentieth century.

In the first biography ever publishedâthe document that finally provided me with enough information to write this essay after a gestation period of twenty-five years!âJoseph Lester, with editing and additional material by Peter Bowler, assessed Lankester's career in a fair and judicious way

(E. Ray Lankester and the Making of British Biology

, British Society for the History of Science, 1995):

Evolutionary morphology was one of the great scientific enterprises of the late nineteenth century. By transmuting the experiences gained by their predecessors in the light of the theory of evolution, morphologists such as Lankester threw new light on the nature of organic structures and created an overview of the evolutionary relationships that might exist between different forms. . . . Lankester gained an international reputation as a biologist, but his name is largely forgotten today. He came onto the scene just too late to be involved in the great Darwinian debate, and his creative period was over before the great revolutions of the early twentieth century associated with the advent of Mendelian genetics. He belonged to a generation whose work has been largely dismissed as derivative, a mere filling in of the basic details of how life evolved.

Lankester's conservative stance deepened with the passing years, thus increasing the anomaly of his early friendship with Karl Marx. His imposing figure only enhanced his aura of staid respectability (Lankester stood well over six feet tall, and he became quite stout, in the manner then favored by men of

high station). He spent his years of retirement writing popular articles on natural history for newspapers, and collecting them into several successful volumes. But few of these pieces hold up well today, for his writing lacked both the spark and the depth of the great British essayists in natural history: T. H. Huxley, J. B. S. Haldane, J. S. Huxley, and P. B. Medawar.

As the years wore on, Lankester became ever more stuffy and isolated in his elitist attitudes and fealty to a romanticized vision of a more gracious past. He opposed the vote for women, and became increasingly wary of democracy and mass action. He wrote in 1900: “Germany did not acquire its admirable educational system by popular demand . . . the crowd cannot guide itself, cannot help itself in its blind impotence.” He excoriated all “modern” trends in the arts, especially cubism in painting and self-expression (rather than old-fashioned storytelling) in literature. He wrote to his friend H. G. Wells in 1919: “The rubbish and self-satisfied bosh which pours out now in magazines and novels is astonishing. The authors are so set upon being âclever,' âanalytical,' and âup-to-date,' and are really mere prattling infants.”

As a senior statesman of science, Lankester kept his earlier relationship with Marx safely hidden. He confessed to his friend and near contemporary A. Conan Doyle (who had modeled the character of Professor Challenger in

The Lost World

upon Lankester), but he never told the young communist J. B. S. Haldane, whom he befriended late in life and admired greatly, that he had known Karl Marx. When, upon the fiftieth anniversary of the Highgate burial, the Marx-Engels Institute of Moscow tried to obtain reminiscences from all people who had known Karl Marx, Lankester, by then the only living witness of Marx's funeral, replied curtly that he had no letters and would offer no personal comments.

Needless to say, neither the fate of the world nor the continued progress of evolutionary biology depends in the slightest perceptible degree upon a resolution of this strange affinity between two such different people. But little puzzles gnaw at the soul of any scholar, and answers to small problems sometimes lead to larger insights rooted in the principles utilized for explanation. I believe that I have developed a solution, satisfactory (at least) for the dissolution of my own former puzzlement. But, surprisingly to me, I learned no decisive fact from the literature that finally gave me enough information to write this essayâthe recent Lankester biography mentioned above, and two excellent articles on the relationship of Marx and Lankester: “The friendship of Edwin Ray Lankester and Karl Marx,” by Lewis S. Feuer

(Journal of the History of Ideas

40 [1979]: 633â48), and “Marx's Darwinism: a historical note,” by Diane B. Paul

(Socialist Review

13 [1983]: 113â20). Rather, my proposed solution

invokes a principle that may seem disappointing and entirely uninteresting at first, but that may embody a generality worth discussing, particularly for the analysis of historical sequencesâa common form of inquiry in both human biography and evolutionary biology. In short, I finally realized that I had been

asking the wrong question

all along.