IBM and the Holocaust (36 page)

This offer, made orally by you, dear Mr. Watson . . . will undoubtedly be greatly appreciated in many and especially responsible circles. . . . We should thank you if you would ask your Geneva organization, at the same time, to furnish us the necessary repair parts for the maintenance of the machines. . . .

Yours very truly,

H. Rottke

cc: Mr. F. W. Nichol, New York

cc: IBM Geneva

43

IBM's alphabetizer, principally its model 405, was introduced in 1934, but it did not become widely used until it was perfected in conjunction with the Social Security Administration. The elaborate alphabetizer was the pride of IBM. Sleek and more encased than earlier Holleriths, the complex 405 integrated several punch card mechanisms into a single, high-speed device. A summary punch cable connector at its bottom facilitated the summarizing of voluminous tabulated results onto a single summary card. A short card feed and adjacent stacker at the machine's top was attached to a typewriter-style printing unit equipped with an automatic carriage to print out the alphabetized results. Numerous switches, dials, reset keys, a control panel, and even an attached reading table, made the 405 a very expensive and versatile device. By 1939, the squat 405 was IBM's dominant machine in the United States. However, the complex statistical instrument was simply too expensive for the European market. Indeed, in 1935, the company was still exhibiting it at business shows.

44

Because the 405 required so many raw materials, including rationed metals that Dehomag could not obtain, IBM's alphabetizer was simply out of reach for the Nazi Reich.

But the 405 was of prime importance to Germany for its critical ability to create alphabetized lists and its speed for general tabulation. The 405 could calculate 1.2 million implicit multiplications in just 42 hours. By comparison, the slightly older model 601 would need 800 hours for the same task—fundamentally an impossible assignment.

45

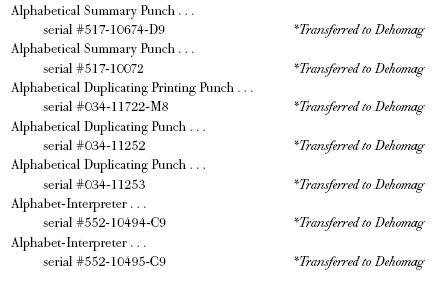

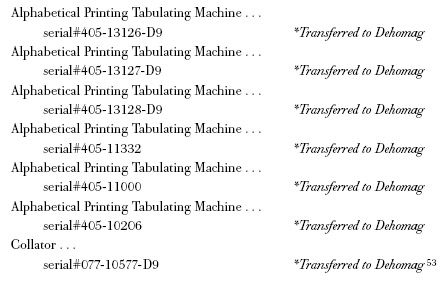

More than 1,000 405s were operating in American government bureaus and corporate offices, constituting one of the company's most profitable inventions. But few of the expensive devices were anywhere in Europe. Previously, Dehomag was only able to provide such machines to key governmental agencies directly from America or through its other European subsidiaries—a costly financial foreign exchange transaction, which also required the specific permission of Watson. Germany had taken over Poland and war had been declared in Europe. Such imports from America were no longer possible. But Dehomag wanted the precious alphabetizing equipment still in Austria: five variously configured alphabetical punches, two alphabetical interpreters, and six alphabetical printing tabulators, as well as one collator. However, these valuable assets were still owned and controlled by the prior IBM subsidiary.

46

Watson would not transfer the assets or give the Austrian machines to Dehomag without something in return. The exchanges began by a return to the issue of Heidinger's demand to sell his stock if he could not receive the bonuses he was entitled to. Watson tried to defuse the confrontation by suddenly agreeing to advance Heidinger the monies he needed. Watson wrote Rottke, "When I was in Germany recently and talked to Mr. Heidinger, he gave me to understand that he was in need of some money to meet his living expenses. As a stockholder in your Company, I am writing this letter to advise you that it will be agreeable to us for you to lend Mr. Heidinger such amounts as you think he will require to take care of his living expenses."

47

Watson's letter, of course, expressed his incidental approval as a mere stockholder—not as the controlling force in the company—this to continue the fiction that Dehomag was not foreign-controlled.

At the very moment Watson was dictating his letter about Heidinger, Germany was involved in a savage occupation of Poland. WWII was underway. So Watson was careful. He did not date the letter to Rottke, or even send it directly to Germany. Instead, the correspondence was simply handed to his secretary. She then mailed the authorizing letter to an IBM auditor, J. C. Milner in Geneva, with a note advising, "I have been instructed by Mr. Watson to forward the enclosed letter for Mr. Hermann Rottke to your care. Would you kindly see that the letter reaches him." The undated copy filed in Watson's office, however, was date-stamped "September 13, 1939" for filing purposes.

48

But Heidinger was not interested in further advances, as these only deepened his tax dilemma. He wanted the alphabetizers and made that known to J. W. Schotte, IBM's newly promoted European general manager in Geneva who acted as Watson's intermediary on the alphabetizer question. On September 27, 1939, the day a vanquished Poland formally capitulated, Schotte telephoned Rottke and a Dehomag management team in Berlin to regretfully explain that Watson refused to transfer the alphabetizers. Instead, Watson merely offered to arrange for Dehomag to take possession of thirty-four broken alphabetizers returned from Russia and lying dormant in a Hamburg warehouse. They could be repaired and rehabilitated back into service.

49

An indignant Rottke refused "most energetically on the grounds that these are 'old junk' in which we are not the least interested." Schotte upped the offer, saying Watson wanted Dehomag to take over the entire Russian territory. Rottke thought the prospect in principle seemed rather attractive because Dehomag could then gain foreign exchange. But, thought Rottke, all the benefits of Russian sales would be negated if the German subsidiary was still compelled to pay IBM NY a 25 percent royalty. Preferring not to verbalize any of that, Rottke simply replied to Schotte that any ideas on servicing the Russian market should be expressed in writing.

50

Returning to the alphabetizers, Rottke repeatedly insisted Schotte call Watson to recommend that he "let us have these few machines." Schotte would not budge, saying they had been "set aside for urgent needs." From Rottke's view, the machines were in Nazi-annexed Austria, a territory now granted to Dehomag, and Watson would not let the Germans deploy the existing machines? Incensed and threatening, Rottke told Schotte, "IBM is big enough to take care of its customers," adding, "depriving us of these few machines might later be regretted." Schotte saw that Rottke's limit was being reached. He promised to call Watson again and convey the sentiment in Berlin.

51

Schotte called Rottke the next morning, September 28, in friendly spirits. It was all just a mistake on Watson's part, he was happy to say. Watson, claimed Schotte, thought the machines had never even been delivered to Austria. Watson had backed down again. Rottke was able to send a letter to Heidinger confirming that Dehomag is "keeping the machines I had asked for until further notice."

52

Dehomag's paperwork was quickly finalized:

Just a week before, on September 21, 1939, Reinhard Heydrich, Chief of Himmler's Security Service, the SD, held a secret conference in Berlin. Summarizing the decisions taken that day, he circulated a top secret Express Letter to the chiefs of his

Einsatzgruppen

operating in the occupied territories. The ruthless

Einsatzgruppen

were special mobile task forces that fanned out through conquered lands sadistically murdering as many Jews as they could as fast as they could. Frequently, Jews were herded and locked into synagogues, which were then set ablaze as the people inside hopelessly tried to escape. More often, families were marched to trenches where the victims, many clutching their young ones, were lined up, mercilessly shot in assembly line fashion, and then dumped into the earth by the hundreds.

54

But these methods were too sporadic and too inefficient to quickly destroy millions of people.

Heydrich's September 21 memo was captioned: "The Jewish Question in the Occupied Territory." It began, "With reference to the conference which took place today in Berlin, I would like to point out once more that the total measures planned (i.e., the final aim) are to be kept strictly secret." Heydrich underlined the words "total measures planned" and "strictly secret." In parentheses, he used the German word

Endziel

for "final aim."

55

His memo continued: "A distinction is to be made between 1) The final aim (which will take some time) and 2) sections of the carrying out of this goal (which can be carried out in a short space of time). The measures planned require the most thorough preparation both from the technical and the economic point of view. It goes without saying that the tasks in this connection cannot be laid down in detail."

56

The very next step, the memo explained, was population control. First, Jews were to be relocated from their homes to so-called "concentration towns." Jewish communities of less than 500 persons were dissolved and consolidated into the larger sites. "Care must be taken," wrote Heydrich, "that only such towns be chosen as concentration points as are either railroad junctions or at least lie on a railway." Addressing the zone covered by

Einsatzgruppe I,

which extended from east of Krakow to the former Slovak-Polish border, Heydrich directed, "Within this territory, only a temporary census of Jews need be taken. The rest is to be done by the Jewish Council of Elders dealt with below."

57

Under the plan, each Jewish ghetto or concentration town would be compelled to appoint its own Council of Elders, generally rabbis and other prominent personalities, who would be required to swiftly organize and manage the ghetto residents. Each council would become known as a

Judenrat

, or Jewish Council. "The Jewish Councils," Heydrich's memo instructed his units, "are to undertake a temporary census of the Jews, if possible, arranged according to sex [ages: (a) up to 16 years, (b) from 16 to 20 years, and (c) over], and according to the principal professions in their localities, and to report thereon within the shortest possible period."

58

Once in the ghetto, the instruction declared, Jews would be "forbidden to leave the ghetto, forbidden to go out after a certain hour in the evening, etc."

59

Heydrich demanded that "the chiefs of the

Einsatzgruppen

report to me continually regarding . . . the census of Jews in their districts. . . . The numbers are to be divided into Jews who will be migrating from the country, and those who are already in the towns."

60

Some 3 million Polish Jews, during a sequence of sudden relocations, were to be catalogued for further action in a massive cascade of repetitive censuses, registrations, and inventories with up-to-date information being instantly available to various Nazi planning agencies and military occupation offices.

61

How much food would the Jews require? How much usable forced labor for armament factories and useful skills could they generate? How many thousands would die from month to month under the new starvation regimen? Under wartime conditions, it would be a marvel of population registration—a statistical feat. No time was to be lost.

The Reich was ready. During summer 1939, the Office for Military-Economic Planning, with jurisdiction over Hollerith usage, had conducted its own study of the ethnic minorities in Poland. By November 2, 1939, Arlt, the statistics wizard who had already surveyed Leipzig Jews and their city-by-city ancestral roots in Poland, had been appointed head of the Population and Welfare Administration of the "General Government," the new Reich name for occupied Poland. Arlt was devoted to population registrations, race science issues, and population politics. He edited his own statistical publication,

Volkspolitischer Informationsdienst der Regierungen des Generalgouvernments

(Political Information Service of the General Government), based in Krakow. It featured such detailed data as Jewish population per square meter with sliding projections of decrease resulting from such imposed conditions as forced labor and starvation. Arlt ruled out permanent emigration, since this would only keep Jews in existence. Instead, one article asserts, "We can count on the mortality of some subjugated groups. These include babies and those over the age of 65, as well as those who are basically weak and ill in all other age groups." Only eliminating 1.5 million Jews would reduce Jewish density to 110 persons per square kilometer.

62