If Chins Could Kill: Confessions of a B Movie Actor (43 page)

Read If Chins Could Kill: Confessions of a B Movie Actor Online

Authors: Bruce Campbell

Tags: #Autobiography, #United States, #General, #Biography & Autobiography, #Biography, #Entertainment & Performing Arts - General, #Entertainment & Performing Arts, #Actors, #Performing Arts, #Entertainment & Performing Arts - Actors & Actresses, #1958-, #History & Criticism, #Film & Video, #Bruce, #Motion picture actors and actr, #Film & Video - History & Criticism, #Campbell, #Motion picture actors and actresses - United States, #Film & Video - General, #Motion picture actors and actresses

"Shoot? Shoot what?"

Only Sam knew for sure -- it turned out that he didn't need me to help plug some hole in his plot, he needed me to help him shut an actor up. Pat Hingle, a great character actor for forty years, had been pestering Sam about why his character never got revenge on the pimp who sold his daughter. Sam never had an answer for him -- until I showed up.

Sam: Okay now Pat, this guy here is going to come up to your daughter and say "Come on, girlie girl, you and me are gonna do the devil's dance."

Bruce: I am?

Sam: Quiet, mister. So Pat, you see this happening, and before this horrible guy can do anything else, you jump in there and save your daughter.

Pat: So, I should rough him up a little?

Sam: A little? Hell, you'd be

pissed.

Don't worry about this guy, he's like a stuntman, you can do anything you want. I think you should choke him, actually.

Pat: Maybe I could throw an arm around his neck from behind.

Sam: Yeah, that's great! Then you throw him down the street and kick him one last time in the ass.

Pat: Okay, sounds good, Sam.

Bruce: Hey, Sam, could I ask a question? Where is my character coming from? Should I come from over there?

Sam took this opportunity to humiliate me in front of the entire crew.

Sam: Oh, so Bruce has questions. Well, maybe we should all just wait while we answer every one to your satisfaction.

Bruce: Well, Sam all I --

Sam: You'll stand where I tell you to stand, mister -- you'll say what I tell you to say -- you'll do what I tell you to do.

Bruce: Okay, Sam, whatever...

After numerous takes of this rough encounter, Pat Hingle seemed pleased. As he walked away a happy camper, Sam approached me.

Sam: Thanks for your help, buddy -- that scene will never see the light of day...

Scott Spiegel was bullied into a role as a scavenger. He too suffered the public wrath of Sam.

Scott: Sam was so funny as the director. He goes, "Okay. Let me hear how you're gonna sound." It was, like, in front of everybody. I mean can't he just pull me off to the side or something? But it was cool --

Bruce: Didn't you hang out with the guy that nobody knew?

Scott: Yeah. Russell Crowe. I met him on a van ride to set. It's seven in the morning. I'm next to Woody Strode and all these character actors --

Bruce: And he fires up a cigarette?

Scott: Yeah. We're in a closed van. And he's listening to like the worst Australian rap music, and I'm like, "What are you doing?"

Bruce: Did you bug Leonardo?

Scott: Well, he was really into what he was doing -- but he and that little blond kid were playing the most childish games. They were playing tag. I'm like, "Will you get out of here?" But I saved a call sheet. It was so cool -- Leonardo DiCaprio, Gene Hackman, Sharon Stone... Scott Spiegel. I'm like, "Oh my God."

40

A MADNESS TO MY METHOD

I once heard that Robert DeNiro lived with a steel-working family for six weeks in order to prepare for his role in

The Deer Hunter.

I've watched interviews with actors who tell wrenching stories of how hard it was to "shake" a character after filming was complete. That's all well and good, but ninety-nine percent of the time an actor is lucky to know what scene is being shot.

Of course, some films have rehearsals where you can work out blocking and discuss every nuance of your character ad nauseum. Since my first film in 1979, I've rehearsed like this maybe two times. Most film projects, and certainly all of TV, simply don't have the time for it.

In this more realistic world of acting, you have to think fast or you'll get buried. My first TV gig,

Knots Landing,

left me speechless. The director introduced himself to me in the morning and never said another word to me for the rest of the shoot. As they were setting up my first shot, I realized that I had no props. Here I was, playing a businessman at a meeting, and I didn't have a watch, a briefcase, or documents of any kind. I quickly wrangled the prop man and got what I needed.

Welcome to TV,

I figured.

On any given day, projects other than big A pictures are gonna shoot between five and eight pages with or without you, so acting can't always be about "method." Often, big dramatic scenes are filmed at inopportune times under the

least

dramatic circumstances. The concept of "intimate" doesn't really apply when there are thirty crew members standing around, and you're the only reason they haven't gone to lunch yet.

What happens when you have to break down in tears and the sun is about to dip below the horizon? I can guarantee you, that big yellow ball doesn't give a hoot about motivation. What if your big scene falls at the end of a twelve-hour day, which always seems to be the case, and you can't even think straight, let alone hit your marks? In situations like that, I say, "Bring on the fake tears. How soon can I get them?"

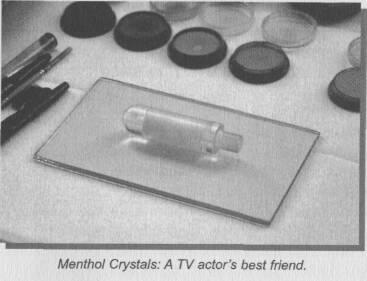

I have often opted for saline drops or, in more extreme cases, menthol crystals, to bring on the waterworks. Menthol crystals work best -- they're packed into a small plastic tube and just before you film, the makeup person blows menthol gas directly into your eye. The results are almost immediate, as your eyes frantically attempt to ward off this semitoxic substance. Every time I think of it, I laugh at the notion that Charlie Chaplin, in his heyday, would let shooting grind to a halt for days on end until he came up with a clever idea. In today's environment, he'd be strung up by his thumbs.

Actors are renowned for changing dialogue, and I'm sure writers love to hang them in effigy, but sometimes there are good reasons for this. Actors bring a fresh eye to the material after a writer has sometimes lost valuable perspective. No matter what writers say to the contrary, I can tell you that any actor worth their salt will analyze their character just as much as the writer has done. During the rewrite process, an actor's input becomes even more crucial. In many cases, a writer will make changes in plot, tone, and dialogue, usually to suit their employer and will fail to "track" the ripple effect on characters throughout the piece.

Granted, actors can also be major bullshit artists -- demands to make dialogue more "organic" should be ignored because it means that the actor doesn't know what they're talking about. More forgiving are demands to make the dialogue suit their personality. I don't buy this a hundred percent either because the actor is, after all, hired to play someone who is

not

them.

Sometimes, an actor will simply do what they can to reduce the

amount

of dialogue. I can tell you, expository dialogue is the hardest to memorize, because it always includes new names of places and people.

"Okay, people, listen up. Willy, you and Jenkins take the Ridgeback Road to Blanding Field by twelve o'clock. George, you and Eddy take the X-ll and make sure those simulators get to White City in one piece, or Captain Murdock will have our asses."

In

McHale's Navy,

Tom Arnold played the leader of a motley crew. It was his job as a character to explain what was going on in almost every scene. To combat this, Tom reassigned lines almost every day.

"Hey, Bruce, you haven't said anything in a couple days, why don't you take this line?"

"Whatever you say, big guy..."

In some cases, an actor can't change a line of dialogue even if he wanted to. This would be common in either the arena of theater, where a playwright's words are more precious, or, in the case of

Congo,

where the writer obviously had enough clout to enforce it.

John Patrick Shanley won an Academy Award for

Moonstruck

and has written a number of plays. I'd be willing to bet my salary on the film that he had a no-changes clause in his contract, because after the first take of my first scene, the script supervisor came up to me with a worried look.

"Excuse me, Bruce -- that last take you added an 'umm,' and a 'well,' and a huh.'"

"Oh, did I? Okay -- what's your point?"

"We really need to keep to this script."

"Exactly?"

She nodded gravely.

I have to tell you, that really pissed me off because when take two came along, all I could think of was,

Am I getting these lines exactly right?

instead of how to best present the idea of the scene. Good lord, I was just trying to smooth out lumpy transitions -- I had no desire to change the

intent.

Aside from all that, let's not kid ourselves -- Congo was

adapted

from another author's novel, so it wasn't even an original screenplay, let alone some play that opened on Broadway to rave reviews -- this was a big, schlock, summer film.

Once you get past the script stuff, you've got to lay out your scene in the form of blocking. I enjoy getting the overall sense of a scene before it's broken down into a million shots. Many directors, particularly those suckled on MTV, lean more toward the technical side and don't really know how to talk to actors. One poor sap, thinking he was laying out the blocking, came over to explain a scene.