If Walls Could Talk: An Intimate History of the Home (21 page)

Read If Walls Could Talk: An Intimate History of the Home Online

Authors: Lucy Worsley

Tags: #History, #Europe

One of the housemaids asked if she could have her hair bobbed…

‘Why should she want her hair bobbed’, her ladyship demanded.

‘I understand it’s the fashion, my lady’.

‘Tell her she must keep it as it is, I don’t want fashionable maids’.

‘Very well,’ said Mr Lee, ‘but I think I should inform you that if you adopt this intransigent attitude you will shortly be lucky to get housemaids with any hair at all’.

Lady Astor dissolved into laughter, and told him that the maids could do anything they wanted with their hair.

Grooming was made easier for men, too, when the cut-throat razor became obsolete. The American King C. Gillette patented the first safety razor with a disposable blade in 1901, and the invention of the electric razor in the 1920s made the then popular pencil-thin moustache and clean cheeks and chin much easier and cheaper to achieve.

Despite the rise of the hair salon, home hairdressing has not entirely disappeared. In my 1970s childhood we were visited by a hairdresser who came to our house and cut our hair as we sat in state upon the kitchen stepladder. That seems like a time long gone, but a fascinating barometer of the recent recession was provided by the increasing sales of hair dye as people cancelled their expensive salon appointments.

Hard times send people back to the bathroom to do their own hair.

20 – War Paint

I now observed how the women began to paint themselves, formerly a most ignominious thing and only used by prostitutes.

John Evelyn, 1654

John Evelyn was charting a change from sobriety to revelry as the serious years of the English Civil War gradually gave way to a more hedonistic and courtly Restoration age. But make-up, long associated with prostitutes, had also been used by royalty and courtiers, actresses and actors. It has always been employed by anyone who needs to play a part before the eyes of the world.

The Tudors literally didn’t know what they looked like. They had no glass mirrors, only the cloudy view provided by polished steel or water. (The royal peacock, Henry VIII, had several of these metal ‘glasses to look in’.) In such an age, it’s not surprising that an exact likeness was low on the list of the requirements of portraiture. Instead, a portrait presented the patron’s abstract idea of what the sitter should look like: usually richly dressed, stately, well-born; but often strangely inhuman, like a cipher not a person.

Grand ladies had their skins daily painted lead-white by their maids to make them look more like the stiff, splendid, stately symbols of lineage and power seen in contemporary portraits.

Jacobean fashions required lengthy doings ‘with their looking glasses, pinning, unpinning, setting, unsetting, forming and conforming, painting blew veins and cheeks’. Paleness was sought because only the labourer was burned by the sun.

The seventeenth century saw the rise of rouge, the rosy cheek and reddened lip. But now the arguments began. The Puritans insisted that sexy and more naturalistic make-up was nothing short of sinful. Paint and perfume represented vanity and self-absorption, and covered up an impure soul. One particularly strident Puritan complained that cosmetics were ‘putrifaction’, and that a painted woman was nothing more than ‘a dunghill covered with white & red’. On 7 June 1650, Parliament even proposed ‘an Act against the Vice of Painting and wearing black Patches and immodest Dresses of Women’ (it never actually reached the statute book).

When Charles II returned from French exile in 1660, he brought with him a daring French fondness for rouge. (His unfortunate queen, Catherine of Braganza, was observed with make-up running down her sweating face during a stifling banquet in 1662.) But red cheeks were still not widely accepted as respectable or even desirable, and ladies’ man Samuel Pepys preferred his prey pale: he found one female acquaintance ‘very pretty, but paints red on her face, which makes me hate her’.

Beauty spots, or black stick-on patches, were originally used to cover pimples or smallpox scars. But the rules for their shaping and positioning soon developed into quite a sophisticated system of meaning. In the reign of Queen Anne, Whig ladies wore them on one cheek and Tories on the other. According to

The Spectator

in 1711, one ‘

Rozalinda

, a famous Whig Partizan’, had the misfortune to possess a natural and ‘beautiful Mole on the Tory Part of her Forehead; which being very conspicuous, has occasioned many mistakes’ about her political allegiance. In the twentieth century, Thomas Harris’s fictional serial killer Hannibal Lecter, delighting in esoteric knowledge,

could still read the language of beauty spots: he was delighted when his beloved FBI agent Clarice Starling acquired a gunpowder scar on her cheek just in the position symbolising ‘courage’.

The positioning of this lady’s face patches proclaims her Whiggish political tendencies

It’s easy to forget just how pustular and pock-marked seventeenth-century skin must have been, with sores and pusfilled spots seen on nearly every face, not just upon the faces of adolescents as today. There were no antibiotics to prevent an infected pustule from possibly becoming a long-lasting and

dangerous wound. James Woodforde, an Oxford undergraduate, writing in 1751, described how he was given great pain by a boil on his bottom. It was bad enough to give him a fever, until luckily it ‘discharged itself in the night excessively’.

Lepers and syphilitics, whose conditions showed upon their skins, were thought to be suffering from moral as well as physical decay, so no wonder there was a strong urge to cover up evidence of imperfection. Skin preparations were largely made and applied at home, from asses’ milk to make ‘a woman look gay and fresh, as if she were but fifteen years old’, to bean-flower water, ‘which taketh away the spots of the face’. Not all of them were benign: the ingredients for Eliza Smith’s Georgian recipe for pimple cream included brimstone, while Johann Jacob Wecker suggested a fingernail preparation containing arsenic and ‘Dogs-turd’.

As well as covering up imperfection, though, make-up heightens femininity, and therefore complements masculinity, so it did become accepted by the men who would otherwise regret their wives looking like prostitutes. ‘Alas! The crimsoning blush of modesty will be always more attractive, than the sparkle of confident intelligence,’ regretted one particularly enlightened male in 1798. ‘Too much’ make-up, though, has in all periods always signalled sexual availability. In 1953, Barbara Pym describes a female character in her novel

Jane and Prudence

with eyelids ‘startlingly and embarrassingly green, glistening with some greasy preparation’. ‘Was this what one had to do nowadays when one was unmarried?’ the narrator wonders. ‘What hard work it must be.’

Make-up for men too grew more important in the eighteenth century. Indeed, the new social stereotype of ‘the fop’ was ‘more dejected at a pimple, than if it were a cancer’. He and his over-groomed friends might use a conical mask to protect their lungs from the powder blown over their wigs and coats ‘abundantly’, while their gloves were ‘essenc’d’ and their handkerchiefs

‘perfum’d’. Then it was ‘time to launch, and down he comes, scented like a perfumers shop, and looks like a vessel with all her rigging under sail without ballast’.

Effeminacy was an accusation frequently flung about in the eighteenth century. While sodomy remained a crime punishable by death, though, men wearing make-up were much more in the mainstream of society than the puritanical, moralistic Victorians would allow them to be. It was the influential Beau Brummell in late eighteenth-century Bath who advocated the scrupulously clean but absolutely unpainted and unperfumed body for men, and this more ‘manly’ ideal persisted throughout the next two centuries.

Female make-up began finally to lose some of its association with prostitution in the twentieth century. Red lips were (and remain) desirable but dangerous, associated with independence and subversion. The suffragettes, revelling in their newfound sense of feminine freedom, adored shop-bought, very red lipstick, so much more enjoyably risqué than beauty products made at home.

The Daily Mirror Beauty Book

of 1910 gives a recipe for lip rouge to be made by the timid or thrifty in their own kitchens: boric acid, carmine, paraffin and ‘Otto of Rose, sufficient to perfume’ are all required. As the suffragette movement gained force and credibility, even the staid and respectable ladies’ magazines began to contain discreet adverts for ready-made make-up.

The next generation, coming of age in 1920, found nothing at all disreputable about lipstick, and it finally became universal and classless. Cinema and television had a great effect on makeup styles; what showed up well on screen was also copied on the street. Greta Garbo was responsible for the pencil-thin eyebrows of the 1930s, and set every cinema-going girl a-plucking. ‘Never take out lip-salve, mirror and powder-puff at the dinner table’ an etiquette guide of the 1920s had to counsel the over-enthusiastic face-painter.

Nurses in hospitals between the wars complained vociferously when they weren’t allowed to wear lipstick, and the princesses Elizabeth (b.1926) and Margaret Rose (b.1930) were brought up to wear make-up as a matter of course. It was now perfectly respectable. It is surprising and a little touching to learn that in 1953 the new queen, quite adept enough, did her own make-up for her televised coronation.

21 – The Whole World Is a Toilet

The sideboard is furnished with a number of chamber pots and it is a common practice to relieve oneself while the rest are drinking; one has no kind of concealment and the practice strikes me as most indecent.

François de La Rochefoucauld on

English table habits, 1784

Having once had occasion to visit the ladies’ at the Goldman Sachs investment bank, I was not entirely surprised to see free tampons provided. What did impress me was the provision of

three different brands

. And it’s always been true that the conditions in which you relieve yourself reveal a huge amount about your social and economic status.

Many people in the Middle Ages simply used nature itself. After all, as the Bible said, every man could use a spade, and ‘it shall be, when thou wilt ease thyself abroad, thou shalt dig therewith, and shalt turn back and cover that which cometh from thee’.

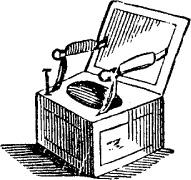

Settlements, however, required more formal arrangements. The Anglo-Saxons under King Alfred began to organise their towns into ‘burghs’, fortified rectangles with a grid system of streets that can still be seen today in places like Winchester and Wallingford. Now communal cesspits were created for

the disposal of waste. I have had the privilege of handling the human excrement from one such pit, excavated in Winchester and kept in the freezer in the town’s museum. Occasionally it is defrosted and lucky visitors are allowed to handle it, and even to pick out the cherry pips which have been proven by archaeologists to have passed right through a Saxon stomach.