Imagined Empires (7 page)

Authors: Zeinab Abul-Magd

The plague visits the different countries of the Ottoman Empire, as the smallpox visits the different countries of Europe: Like the latter, it neither owes its origin to putrid exhalations nor to causes derived from the soil or the climate. . . . The plague visits Turkey and makes its appearance more or less often in a town, according as commerce or communications are most or less frequent. . . . Egypt carries on a somewhat considerable trade with Constantinople; and indeed, it commonly happens that the Turkish ships or caravels belonging to the Grand Signior bring the plague to Alexandria, where it spreads to Rosetta, Damietta, and Cairo, and thence into all the villages.

94

The plague was pandemic throughout the empire from the beginning of the sixteenth to the mid-nineteenth century, causing a mortality rate of up to 70 percent in the affected places. The eighteenth century witnessed many waves of this epidemic in the Mediterranean basin of the empire;

95

and in a sense, Istanbul “traded” the epidemic with Cairo.

96

As Upper Egypt was now an integrated part of the empire's political and commercial system, Mamluk ships gained access to the southâfacilitated by their wars on Upper Egyptian soilâand they carried imperial diseases with them. In the 1780s, the ships of two Mamluk factions of the new regime, led by Ibrahim Bey and Murad Bey, fought each other in Upper Egypt in what was also a time of low Nile inundation and food shortage. Furthermore, other dissident factions continued to take refuge in Upper Egypt. These troops without a doubt transmitted the

epidemic to the south, especially since numerous Mamluk warlords of this period died from the plague while in Upper Egypt or after their return to Cairo.

97

With the plague and Mamluk oppression in Upper Egypt, subaltern rebellion became a daily practice of the inhabitants of the towns, villages, and mountains in the desert. Nomadic Arab tribes and Coptic peasants in particular faced increasing oppression during this period. They rebelled in various ways against the empire and its Mamluk government. Their discontent was more distinctly expressed when the Napoleonic campaign arrived in Egypt, between 1798 and 1801, as many members of these two groups supported the French soldiers against the Mamluk army.

As for the unsettled Arab tribes, their rebellion was incited by both racial and economic factors. In the past, these roaming tribes had submitted themselves to the Hawwara primarily because they shared Arab tribal blood with them but also because of the economic advantages that the Hawwara provided. Arab tribes were, as an eighteenth-century European traveler put it, “looking down with contempt on Turks,” and they believed that their lineage could be traced to Ishmael and was therefore superior to that of the Turks.

98

They detested the new domination of the northern Mamluk elite, who were a foreign oligarchy of Turco-Circassian origin. In addition, the Mamluk elite discontinued the Hawwara practice of offering economic privileges to the Arab tribes in exchange for safe passage on highways. As a result, the tribes returned to plunder, highway robbery, and raiding villages to both disturb the foreign state and make a living.

99

For instance, al-Jazzar Pasha, the Ottoman governor of Syria, indicated in his 1785 report to the sultan that when the Mamluk officers suspended the salaries of the âAbabida tribe in Qina Province, the frustrated members of the tribe exacted revenge by attacking travelers, pillaging villages, and destroying crops. A battle erupted between the two sides in which the strong, proficient warriors of the âAbabida emerged triumphant. The conflict was settled only when the âAbabida fully received their payment in addition to blood money for those who were killed in the battles. The two sides then wrote a deed registered in one of Qina's shariâa courts to confirm the settlement and record the terms of the ceasefire. Thousands of similar battles erupted between the Mamluks and Arab tribes. Al-Jazzar did, however, note that friendship between the Arabs and the Mamluks was not impossible.

100

The âAbabida tribe embarked on another more radical rebellion when they supported the French troops in Upper Egypt against the soldiers of the

sultan. As soon as the French arrived in Egypt, their troops headed to Upper Egypt in order to occupy the rich region and control its agriculture and trade routes. The âAbabida befriended the French officers and provided them with logistical support during the battles. Vivant Denon, an Egyptologist who accompanied the campaign, reported that during a battle in the Qusayr port on the Red Sea, “we entirely gained their [the âAbabida] friendship by exercising with them in mock charges and showing so much confidence in them.”

101

Similarly, peasant Copts, who suffered tremendously under Mamluk oppression after the collapse of Hammam's nearly ideal state, supported the troops of the French occupation. Like the âAbabida tribe, Coptic peasants of Qina sided with the Christian invaders during the battles in their province. Denon asserted that commoner Copts sympathized with the French army because of their extreme animosity for the Mamluk troops who had plundered Coptic villages, such as Nagada, during the war. Denon said that “[the Copts'] zeal induced them to come and give us all the intelligence that they had been able to collect.”

102

After the campaign's defeat and the French departure from Egypt, the Ottoman sultan needed to propagate a new imperial discourse of hegemony in order to address the resentment in Upper Egypt. Sultan Selim III restored the one-state system and, once more, installed Mamluk military elite as rulers of Upper Egypt. Nevertheless, he sent a series of decrees (

ferman

s) to Qina and the other provinces in Upper Egypt to appease and co-opt different discontented groups. The Ottomans incorporated the south's local shariâa law into the more centralized state apparatus and used the court system to disseminate these decrees. The sultan deployed a religious rhetoric, emphasizing his position as the “caliph” of Muslims who had defeated infidel invaders. One of the

fermans

arrived immediately after the French departure and expounded the sultan's policy of reconciliation with the peasants and Arab tribes of Qina, especially after the massive destruction that the Mamluk armies had inflicted on these two groups while fighting the French for the Ottomans. The same decree also aimed at incorporating all power groups in Upper Egypt into a new imperial order.

103

This elaborate decree, as received by Isna Court, addressed elite and subaltern groups alike, including shariâa law scholars, judges, Arab tribal leaders, village shaykhs, and peasants. After declaring victory over the French, the sultan affirmed that it was his duty to protect and guard the poor inhabitants of the countryâa mission entrusted to him by God as the caliph of Muslims. The decree added that some Mamluk soldiers had arbitrarily accused groups of

peasants, Arab tribal leaders, and Bedouins of collusion with the French and consequently had confiscated their grain, animals, and wealth. The affected groups expected the sultan to apply a firm punishment to the transgressive soldiers. Instead, the sultan stated his plan to relocate the offending Mamluks outside of Egypt and bestow upon them lands and houses in other provinces in the empire, as a reward for defeating the French. The sultan implied that Upper Egyptian peoples whom they had hurt would never have to see them again, and a new Mamluk government hopefully would be more just.

104

Another decree from Istanbul dealt with the Copts as a religious minority. Upper Egyptian Copts who had supported the French were clearly in trouble with both the Mamluks, who now had reasserted their authority, as well as the local Muslim population. The new regime forced these Copts from their homes and confiscated their properties. The Copts raised a petition to the Ottoman sultan, requesting protection and the retention of their properties. In response, Sultan Selim III promulgated a decree in 1801, also disseminated through Qina's and other provincial shariâa courts, commanding the Muslim inhabitants of Upper Egypt to pardon the Copts who had supported the infidel French. The decree implored religious dignitaries, laypeople, and peasants to treat Copts with dignity and respect, indicating the belief that they had only cooperated with the French out of fear and the desire to protect their families and properties. The sultan asserted that the Copts had followed and obeyed the French only by force. He stipulated that they must return to their homes in peace and resume the tranquil life they had enjoyed before the political turmoil:

A

ferman

from his majesty Sultan Selim, may God give him victory . . . to the authorized court deputies [local judges] . . . and the country shaykhs . . . [decrees] that during the French infidels' seizure time, the Copts coercively followed the French infidels in order to protect their honor [

aâaradahum,

i.e., families] and fortunes. Even if what they did was not accepted, they shall return to their home places and live in their houses in comfort and safety as they were in the past. Because they are in all cases the subjects

[raâiyya]

of our Sublime state and they petition for protection against all matters. From now on, nobody should intrude upon them because of their support of the French. They should buy and sell and take and give [freely] as they used to do in the past.

105

The Ottoman Empire's attempt at establishing hegemony would fail just a few years later, when the rising empire of Muhammad âAli Pasha (r. 1805â48) took control of the entirety of Egypt.

TWO

The French, the Plague Encore, and Jihad

1798â1801

In 1798, when Napoléon Bonaparte's army landed in Egypt, its declared goal was to liberate the country from the despotic rule of the Ottomans. Granting freedom to the country's minority of Orthodox Christians, the Copts, was the second task of the French colonial troops. Upon arriving in Egypt, the soldiers advanced from Cairo into the south, Upper Egypt, where the Coptic population was concentrated. As expected, Christian inhabitants received the French with admiring eyes and tender hearts. The Copts provided the French with extensive logistical support until the French triumph over the tyrannical Mamluksâthe Turkic ruling elite appointed by the Ottomans. An Egyptologist who accompanied the troops to the south, Vivant Denon, depicted scenes in Qina Province of passionate Copts aiding the French, crying at the sight of their forces leaving for the battlefields. Of one incident, Denon wrote, “I was struck with the sincere interest which the sheik [chief Copt] expressed for our fate, who, believing that we were marching on to a certain death, gave us the most circumstantial advice, without concealing from us any of the dangers to which we were exposed, advised us with great judgment on every particular which could render the encounter less fatal to us, followed us as far as he could, and parted from us with tears in his eyes.”

1

Nevertheless, after the French won the wars and established a colony in Egypt, the romantic image of supportive natives awaiting their liberators was soon shattered. The Copts, in fact, were manipulating and exploiting the French for their own interests. As soon as the new administration hired them to run the taxation system, Coptic accountants controlled the colony's finances and denied the French access to files. Copts were not the only native group that acted in this manner or that manipulated the French with false impressions of welcoming locals. Many Arab tribes, as oppressed by the

Mamluks as the Copts had been, similarly showed a friendly, hospitable face and supported the French troops during the battles. They later excluded the colonial administrators from local governing councils and denied them access to decision-making institutions in villages.

2

The French Empire's campaign in Egypt was a conspicuously failed attempt at colonization in the Middle East that lasted for only three years. In 1801, Napoléon's troops were defeated by British troops allied with the Ottomans, and the French were soon forced to depart from Egypt. However, this chapter argues that military misfortune was not the reason behind the rapid failure of the French Empire. Rather, it was a crisis of images. Before and during the campaign, French experts on the Orient forged one image of inferior and oppressed natives waiting for an enlightened nation to liberate them, and another image of the colonial self as exactly this liberator. Moreover, the colonial self was imagined as a competent exploiter of the colony's immense resources, which were allegedly underutilized. As the troops encountered the harsh reality on the ground, these images were demolished, putting the empire in deep crisis.

Upper Egypt, especially Qina Province, was a distinct site where this plight was exposed. The population of the south consisted mainly of two groups that the revolutionary French Republic came to liberate: Copts and Arab tribes. These two groups both deliberately perpetuated the discursive construction of false images in order to take advantage of the French. When the truth was revealed, it was too late for the confused colonizer to escape. As this chapter recounts, the French faced a fierce holy war of Jihad launched by local and regional Arab insurgents and had to reinstall the very ancien régime they had originally come to depose. Shortly afterward, the failed empire brought about environmental destruction to the south: a massive wave of the plague swept Upper Egypt.

Postcolonial theory pays much attention to the issue of image making within contexts of modern imperialism. The colonizerâwho was in the position of controlling knowledge productionâcreated reductionist visions of the colonized in order to simplify the process of imperial hegemony. This is the problem of “representation,” as theorists of the field refer to it, where voices from the empire authoritatively described silent natives and presented simplifying categorizations and stereotypes that assisted in the domination of the colonized. Postcolonial theory largely presumes that representation was a unilateral process in which the colonizer solely controlled the production of images and imposed them on the represented natives.

3

Nonetheless,

this chapter shows how image making was a bilateral process to which the natives equally contributed through deceit and manipulation of the empire. The encounters between the French and the Copts and Arab tribes in Upper Egypt during Napoléon's campaign are but one illustrative case.

Edward Said's

Orientalism

is one of the canonical texts that established the concept of representation in postcolonial theory. Said relies on Michel Foucault's vision concerning the inseparable relationship between knowledge and power to argue that European experts on the Middle East created a body of knowledgeâin the form of reductionist stereotypes of Arabs and Muslimsâthat directly or indirectly served imperial ends. “Such âimages' of the Orient as this are images in that they represent or stand for a very large entity, otherwise impossibly diffuse, which they enable one to grasp or see,” Said writes.

4

He asserts that imperialist Europeans controlled the production of these images with almost no interference from the natives. “The scientists, the scholar, the missionary, the trader, or the soldier was in, or thought about, the Orient because he

could be there,

or could think about it, with very little resistance on the Orient's part,” Said asserts.

5

Thus, Said grants the natives a minimum role in creating these stereotypical representations.

In the case of Upper Egypt, the natives did play an important role in making the stereotypes: the inhabitants of Upper Egypt perceived Europeans as naïve, and sometimes foolish, foreigners and potential subjects of exploitation. This is precisely what created a crisis of images in the French Empire's colonial propaganda in southern Egypt and generated other military crises that undermined the empire's allegedly liberationist endeavor. As the holy war of Jihad and the epidemic of the plague in Upper Egyptâand particularly in Qina Provinceâindicate, the French campaign proved to be an environmentally scarred endeavor of a trapped empire.

IMAGE MAKING, DECISION MAKING

During the two decades that preceded Napoléon's campaign, a number of French “experts” visited Egypt to explore the country and produce scientific knowledge to aid in potential colonization. Their published records presented detailed recommendations to the old and new governments, or the ancien régime and the revolutionary French Republic, about how to use the agricultural and commercial sources of northern and southern Egypt. More importantly, their writings served as a foundational tool in an ongoing process of image making about the oppressed, barbarian native and the enlightened, liberating self. These writings portrayed an intelligent Frenchman who was able to go anywhere on earth, quickly learn the culture and investigate the resources of this place, and cleverly develop those resources. These foundational texts served as trusted authorities and propaganda pieces in the process of decision making, inside the French Republic's government and Parliament, concerning dispatching the military expedition to the Orient.

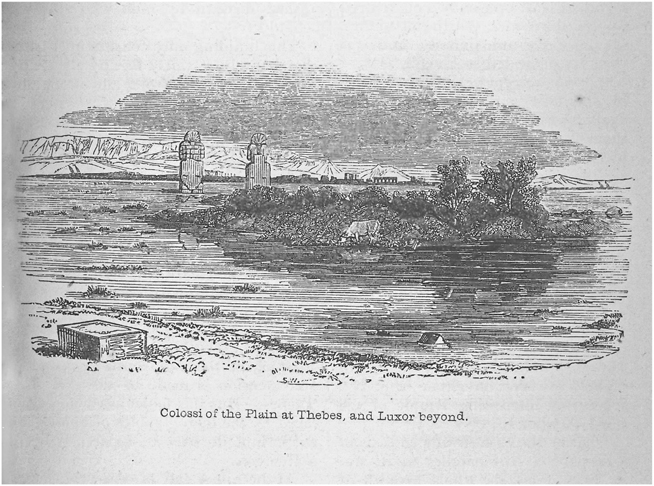

FIGURE 3.

Luxor Temple and plain.

French travelers visited Egypt and reported about it centuries before Napoléon's arrival, especially after it became an Ottoman province in the sixteenth century. Since early travelers were mostly Christian pilgrims passing through holy places in Egypt and Palestine, they mainly sent back to France romantic accounts about biblical and holy sites. In the eighteenth century, the age of European secular enlightenment that glorified pre-Christian legacies of Western civilization, French travelers paid extensive attention to Greek and Roman relics in Egypt and romanticized Egyptian ancient sites. They were also sure to comment on the flourishing trade of this country, especially in Upper Egypt, which brought exotic luxuries of the Indian Ocean to Cairo and the Mediterranean.

6

Finally, by the end of the eighteenth century, in the

age of European imperial ambitions, French accounts mixed this romanticized view of ancient times with strategic geopolitical and economic observations. More than simple pilgrims or travelers, French visitors to Egypt were increasingly scientists, philologists, archaeologists, and the like, some of whom were officially sent by the French government on formal missions to explore the possibility of creating a colony in this resource-rich land.

M. Savary probably presented the first systematic account of France as the needed liberator of the Egyptians from the Ottoman despots and their installed military regime of foreign Mamluks. Savary explored Egypt in 1779, nearly twenty years before Napoléon's Egyptian campaign. His published

Lettres sur l'Ãgypte

was a blunt proposal for colonialism. In the eyes of contemporary Europeans, Savary was a true scholarly expert. An English literary journal commended his “erudition and capacity” and asserted that he “has shown himself well versed in ancient and modern writings concerning Egypt and its antiquities.”

7

With an informed tone, Savary indicated that Egypt was a country of immense resources, but it was unfortunately inflicted with the “ignorance” of the native Egyptians and the “tyranny” of the Mamluk rulers. Turks, Arabs, and Copts were all “barbarians” neglecting great potential sources of wealth and paying no attention to magnificent monuments. Only an enlightened nation that appreciated art and cultural history, such as France, could restore the riches of this land and return it to its ancient glory after centuries of backwardness.

In Qina Province, Savary formed the most important colonial argument, asserting that the occupation of the south would bring about French control over global trade. He observed that Qina's Red Sea port of Qusayr was a meeting point of Indian, Arabian, East African, North African, and Egyptian commerce but lamented how Mamluk despotism and Bedouin raids had reduced the port city's traditionally robust trade. He advocated using Qusayr to turn Egypt into “the center of commerce in the world,” uniting Europe and Asia.

8

Savary even suggested digging a canal between Qusayr and the city of Qinaâthe seat of the province that was a southern Nile port and entrepôtâin order to connect the Red Sea to the river and ultimately the Mediterranean. In the late eighteenth century, caravans had to spend three days carrying Indian and Arabian commodities from the eastern desert to Qina. In ancient times, there had been a canal connecting Qina to Qusayr, but the Turks neglected it and let it dry out. Savary proposed to revive this canalâalmost a century before another Frenchman proposed digging the Suez Canal for similar goals:

Were Egypt subjected by an enlightened people, the route to Cosseir [Qusayr] would be safe and commodious. I even suppose it possible to turn an arm of the Nile into this deep valley, over which the sea formerly flow. Such a canal appears not more difficult than that which Amrou cut between Fostat and Colzoum [Cairo and Suez], and would be much more advantageous, since it would abridge the voyage of the Indian shipping a hundred league, and through a perilous ocean, across the farther and narrow part of the Red Sea. The cloths of Bengal, the perfumes of Yemen, and the gold dust of Abyssinia would soon be seen at Cossier; and the corn, linen, and various productions of Egypt, given in return. A nation friendly to the arts [i.e., France] would soon render this fine country once more the center of commerce of the world, the point which should unite Europe to Asia.

9

Upper Egypt was an important region for Savary's colonial proposal to develop the agriculture of the country, again after liberating it from despotism. He lamented that twelve thousand years of Arab and Turkish rule had degraded Egyptian agriculture. Whereas ancient Egypt had fed millions in the Roman Empire, the annual produce of the country was decreasing due to the ignorance of the present government, which neglected cultivation, just as it did trade. The Egyptian peoples themselves, Savary sympathetically added, were suffering from the rule of foreigners who were not farmers themselves; they endured arbitrary taxes and lacked means of subsistence. The poor peasants had to sell their machines to pay taxes.

10

However, he did not look highly upon those peasants he sought to liberate. The Arabs, he opined, had lost their good faith under the tyrants. Copts were not much different. Despite being the descendants of ancient Egyptians, Copts had lost the sciences of their ancestors but had kept a “vulgar” ancient language.

11