Impeached: The Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln's Legacy (28 page)

Read Impeached: The Trial of President Andrew Johnson and the Fight for Lincoln's Legacy Online

Authors: David O. Stewart

Tags: #Government, #Presidents & Heads of State, #Executive Branch, #General, #United States, #Political Science, #Biography & Autobiography, #19th Century, #History

Other mysterious epistles concerned New York Collector Henry Smythe. In late April, Colonel Moore received a report that Senator Pomeroy, now supporting impeachment, claimed to have a letter from Smythe “showing expenditures on behalf of the President,” adding that the letter “might do Smythe great harm.” A troubled Smythe sneaked into Washington that evening, avoiding the main hotels. Despite his stealthy entrance, Smythe was immediately accosted by an agent of Ben Butler. Butler’s man hustled the New Yorker to a meeting with the Massachusetts congressman. Butler accused Smythe of trying to buy senators’ votes, and backed up his accusation with letters acquired, according to Smythe, by “stealth and trickery.” Smythe’s account so alarmed Colonel Moore at the White House that he begged Smythe to determine whether the stolen letters came from Moore’s desk in the Executive Mansion, or perhaps his wastebasket.

A day later, Smythe was back at the White House, reporting that the stolen letters (now in the possession of War Secretary Stanton) were torn, so they probably came from Moore’s wastebasket. Because the letters mostly damaged Smythe, not the president, they were never released publicly.

As the Senate vote neared, the Kansas postal agent (Legate) continued to press his bribery scheme with the help of Willis Gaylord, Senator Pomeroy’s brother-in-law. For at least a week during the beginning of May, Legate was in regular contact with Cooper at Treasury. At the same time, Gaylord demanded $10,000 from Indian trader Fuller to “negotiate for votes.” Gaylord still offered to sell the votes of Pomeroy and four other senators, in return for cash.

As a matter of simple politics, Gaylord’s persistence was puzzling. By this point in the trial, Pomeroy was acting as a whip for the impeachers, pressing senators to vote for conviction and maintaining a running tally of likely votes. Indeed, after his initial flirtation with the president’s camp, Pomeroy seemed to have struck a deal with Ben Wade, the Senate president pro tem, which would grant the Kansas senator control over Kansas patronage in a Wade Administration. It would take a prodigious contortion for Pomeroy now to vote for acquittal. Perhaps, for the right price, the Kansas senator was prepared to perform such a gyration. His graft-ridden career suggests that he might not have blanched at doing so. Perhaps Pomeroy proposed to sell the votes of other senators, but not his own. Or perhaps Gaylord and Legate intended to steal the supposed payoff money themselves and did not much care what Pomeroy planned to do. Once they had their hands on any bribe money, what could anyone do to get it back? Whatever the explanation, the Kansans persevered.

After the trial’s closing arguments finally ended, Legate told Cooper that he would leave Washington City unless their business was arranged by 3

P.M.

the next day. When the Treasury official responded coolly, Gaylord and Legate tried a different approach. At a meeting with Cooper, Gaylord presented yet another letter from Pomeroy. This one authorized Gaylord to act on the senator’s behalf. “I will, in good faith,” the letter stated, “carry out any arrangement made with my brother-in-law, Willis Gaylord, in which I am a party.” After the meeting, Gaylord tore up Pomeroy’s note. As a precaution, Legate retrieved the scraps, reassembled the letter, and took photographs of it. Just in case. Shortly thereafter, Cooper claimed to Legate that he did not close the deal with Gaylord because the president’s men already “had votes enough to acquit.”

The Astor House group pressed on. By May 7, two days after the gathering in Thurlow Weed’s suite, Astor House conspirators in Washington were sending urgent messages for assistance.

General Adams, the source of the initial bribery proposal, telegraphed Collector Smythe: “To be decided next Tuesday [in one week]. Come on yourself immediately.”

A clamor arose from Washington for Hugh Hastings of Albany, Weed’s man. Woolley, the Whiskey Ring lawyer, and Seward aide Erastus Webster both demanded Hastings’s presence in Washington City. After a day of anxiety, the reassuring news came that Hastings would arrive in the morning, with an essential letter in hand. What was the letter? Was it a tool for blackmail? Would it trigger the release of funds? How did Hastings get it?

Sam Ward, the King of the Lobby and now an ally of the Astor House group, asked a New York client whether the president’s supporters had a plan if the vote went against Johnson. Not to worry, came the answer. One hundred thousand dollars (at least $1.4 million in today’s values) had been raised against that contingency. The president’s lawyers would be paid from that fund, with the balance to go to Johnson “for faithful service.” If Johnson was not convicted, he would still receive $50,000. Money for this purpose—again managed by the assistant treasury secretary, Edmund Cooper—came in part from employees at the Baltimore and Philadelphia custom houses. At the trial’s end, the defense lawyers (Stanberry, Curtis, Groesbeck, Nelson, and Evarts) each received $2,125, an amount raised by Seward, Cooper, and Postmaster General Randall. The lawyer fees totaled less than $11,000. No one has traced the rest of that $100,000. After the trial, Ben Butler noted the contrast between the modest fees paid to the president’s lawyers and the large sums raised for the supposed purpose of paying them. “Raising money for the President’s counsel,” he concluded, was “only a means to procure the acquittal of the President” by bribery.

The efforts of the dark men were no secret to Butler and his operatives. The House manager resolved to uncover and reveal the bribery schemes. Searching for a weak spot in the President’s team, Butler entered a high-stakes chess match with Cornelius Wendell, the corruption professional who had designed the president’s acquittal fund.

Convinced that Wendell knew about all the plots to bribe senators, Butler offered through intermediaries to pay Wendell $100,000 to disclose the perfidious details. The negotiations reached a critical point. Butler drove in a closed carriage to a location near Wendell’s home on F Street, behind the Patent Office. The Massachusetts congressman waited in his carriage while his agents tried to persuade Wendell to join him. After two hours of palaver, Wendell demurred, objecting that he had no witnesses to back up his story.

Butler rode home with disappointment as his companion. He may have wondered whether Wendell had wanted to trap

him

in an overt act of bribery. For all of his spies and suspicions, Butler failed to expose the corrupt schemes of the president’s defenders—not the workings of the Astor House group, not the cabal of greedy conspirators from Kansas, and not the acquittal fund assembled by the three Cabinet secretaries. Knowing there were evil deeds afoot, he still needed proof.

MAY 6–12, 1868

There is much the same feeling here in reference to impeachment that there is in the army the night before a battle. The same fluctuation in feeling, of hope and fear. I don’t see how we can lose, and yet we may.

R

EP.

J

AMES

A. G

ARFIELD

, A

PRIL

28, 1868

F

IVE LONG DAYS

passed between the end of Bingham’s closing argument and May 11, the date when the Senate would meet in executive session and senators could explain their intended votes. Until then, the suspense and anxiety would only build.

The impeachers met directly with wavering senators to cajole, reason with, and threaten them. “Butler and Stevens,” wrote one correspondent, “have not attempted to restrain their pugnacious tendency to anti-impeachment Senators; they have given full vent to their feelings.” More Republican officials came from around the country to agitate for the president’s conviction. According to some reports, doubtful senators were receiving death threats. Wherever they went in Washington, they were watched and overheard, every ear alert for a whisper of commitment to one side or the other.

Republican newspapers applied their own pressure. Horace Greeley of the

New York Tribune

pledged to Stevens that his paper would “keep up a steady fire on the impeachment question till the issue is decided.” He asked Stevens to supply him with “any fact or suggestion…that seems calculated to aid us.” Senator Fessenden of Maine complained that because he was widely understood to favor acquittal, “[a]ll imaginable abuse has been heaped upon me by the men and papers devoted to the impeachers.” The other Republican senator from Maine wrote a passionate letter to Fessenden urging him to vote for conviction. If he went the other way, his colleague warned, “the sharp pens of all the press would be stuck into you for years, tip’d with fire, and it would sour the rest of your life…. You cannot afford to be buried with Andrew Johnson.”

Anti-Johnson forces congregated in the offices of General Grant and War Secretary Stanton, where they traded information and coordinated their efforts. Grant had emerged as the impeachers’ most potent asset. Republican senators had many reasons to accede to the general’s wishes, not solely out of respect for the man. With the Republican convention only two weeks away—it was scheduled for May 20 in Chicago—Grant would soon be the head of the national party and the likely next president. If elected, he would control the reservoir of federal patronage that the Astor House group was fighting so hard to hold on to.

The general-in-chief met quietly with individual senators. He visited the Indiana Avenue home of Frederick Frelinghuysen of New Jersey, who agreed to remain true to the Republican cause. Grant had less luck with William Fessenden of Maine and John Henderson of Missouri. While riding with Henderson on a streetcar, Grant sputtered that Johnson should be removed from office “if for nothing else than because he is such an infernal liar.” Henderson later recalled his own reply: “On such terms, it would be nearly impossible to find the right sort of man to serve as President.”

With the vote shaping up as extremely close, the impeachers turned their attention to Senate President Pro Tem Ben Wade, who would succeed Johnson if the Senate convicted. Wade had taken the juror’s oath, ignoring objections that his interest in becoming president should bar him from deciding the case. Since then, however, Wade had not voted on any procedural and evidentiary question. Now, the impeachers argued, he could no longer afford to be so concerned with appearances. His vote was essential. Ohio was entitled to be represented in the final tally, they added, and the nation was entitled to be rid of this president.

Some Republicans contrived a ploy for preserving Wade’s integrity while increasing their chances of winning a conviction. Wade could resign as president of the Senate just before voting against Johnson. If Johnson were convicted, House Speaker Schuyler Colfax would move into the White House as the next official in the line of succession to the presidency. Wade, though not president, would preserve his reputation and serve the nation. As an inducement to take this self-denying step, Wade was offered the Republican nomination for vice president. Best of all, the switch would make it easier to convict Johnson. The amiable Colfax (nicknamed “Smiler”) would be a less alarming successor to Johnson. Senators who feared Radical Ben Wade in the White House would not have the same anxiety about Colfax.

Wade said no. Plans went forward to swear him in as the new president as soon as Chief Justice Chase announced a “guilty” verdict on any impeachment article.

Yet the prospect of a Wade presidency continued to drag down the drive for conviction. Wade supported an immediate increase in the tariff on imported goods, an emotionally charged position that dismayed many Republicans. “The gathering of evil birds about Wade (I refer to the tariff robbers),” wrote the editor of the Radical

Chicago Tribune

, “leads me to think that a worse calamity might befall the Republican party than the acquittal of Johnson.”

On May 9, a Saturday, two ceremonies marked the horrors and consequences of the late war, reflecting the strains that lay just below the surface of the impeachment trial. Groups of Virginians visited the nearby battlefields at Bull Run, decorating the graves of rebel soldiers who fell there. They planned a Confederate memorial for the site. Simultaneously, the General Conference of the African Methodist Episcopal Church convened in Washington. Two Union generals from the Civil War gave speeches to the delegates.

The president, beyond the power of his lawyers to restrain him, granted another exclusive press interview. This one was with the correspondent of the

Boston Post

, who conveniently enough was Johnson’s own secretary, William Warden. Writing on May 10, Warden found that Johnson “has never looked better than he does to-day, and his fine flow of good humor indicates anything but a troubled mind.” After expressing confidence in the Senate’s judgment, and his willingness “cheerfully” to bow to its authority, Johnson’s gorge rose when questioned about House Manager Bingham’s suggestion that Johnson might refuse to vacate his office if the Senate convicted him. Bingham’s suggestion was “base,” the president said, though “in perfect harmony with the charges and suggestions contained in the eleven articles of impeachment.” If Johnson had to leave his office “according to the forms and requirements of the Constitution,” he said, he would be pleased to do so.

Talking with another correspondent a couple of evenings later, Johnson pointed to a list of the fifty-four senators and asked his guest to indicate how each would vote. The president showed “a cool, deliberate interest” in the tally. Though he liked to portray himself as unconcerned with the trial, the president—like everyone else in Washington City—was counting the votes very carefully.

On the mild morning of Monday, May 11, the Capitol hummed with excitement. The atmosphere mingled, according to one observer, the elements of a presidential election, a public execution, and a lottery drawing. After weeks of listening to witnesses and lawyers, the senators themselves would be able to talk about whether Andrew Johnson should be convicted. Their speeches could reveal the fate of the president, and of the nation.

At Manager Stevens’s home, the day began with a poignant visit from officials of the African Methodist Church. After a minister praised him, Stevens told them of his joy that the black men were now his fellow citizens. He did not deserve their flattering remarks, he continued, but would “try to deserve them in the few years he had left to live.” Ever partisan, the congressman reminded his guests that it was the Republican Party that ended slavery.

The Senate session began at 10

A.M.

and lasted into the night. Though it was an executive session, the senators were free to describe the speeches to outsiders, and so they did. Whenever a senator left the chamber, he was cross-examined by House managers, reporters, and agents of both sides, all desperate to know how the numbers were sorting out. The Astor House group was well represented. Charles Woolley, the Whiskey Ring lawyer, described himself as in the “look out chair.” Collector Smythe and Indian trader Fuller were there, too.

Predictions about Johnson’s chances continued to shift with the rumors of the hour. A week earlier, Republicans had been eager to bet on conviction, even offering odds to Johnson supporters. By May 11, the betting line had shifted to even, with a suggestion that the pro-Johnson money was holding back to avoid moving the line further.

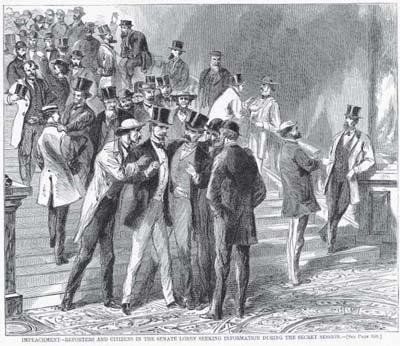

“Reporters and Citizens in the Senate Lobby seeking information about the secret session.”

Only about a third of the senators spoke during the May 11 session, and several were more confusing than enlightening. A few questions were answered. Grimes, Trumbull, and Fessenden openly declared for acquittal. In private remarks, Fowler of Tennessee dashed the hopes of impeachers. He, too, would vote to acquit. George Edmunds of Vermont said he would support conviction on the first three articles, but not on the conspiracy articles. John Sherman of Ohio left more than a few heads shaking. He announced he would oppose Article I, which charged that the firing of Stanton violated the Tenure of Office Act. Because Sherman had chaired the committee that produced that statute, his views on that question might have persuaded other senators. But Sherman also said he would support Articles II and III, which alleged that the appointment of Lorenzo Thomas violated the statute. Sherman’s reasoning was elusive at best. John Henderson of Missouri declared he would vote against the first eight articles. Maddeningly, time expired before he could announce his view of the last three. Several doubtfuls sat silent, not committing themselves one way or the other.

As the afternoon progressed, the impeachers in the lobby grew dismayed. With the confirmation of Republican defections, one Radical recalled, “An indescribable gloom now prevailed among the friends of impeachment.” Another described the experience as being like “sitting up with a sick friend who was expected to die.” In the crowd outside the Senate Chamber, Managers Boutwell and Wilson were steadfast. John Logan was downcast. Bingham talked with friends while Butler stalked the rotunda and corridors with anxious defiance. Thad Stevens, ailing, had stayed home. When the dinner recess arrived, Republican hearts sank at the sight of several doubtfuls trooping off to dine with Chief Justice Chase, who was known to oppose conviction.

By evening, though, the impeachers’ spirits rallied as they dissected the opinions in the Senate Chamber. Some doubtfuls, they realized, were still uncommitted and might yet come through. Even doubtfuls who opposed most of the impeachment articles might vote for a single article, helping the impeachers reach the magical two-thirds total on at least one charge. Conviction on a single article would remove Johnson from the White House. The nervous energy grew until the Senate adjourned at 10

P.M.

The vote would take place on the following day. The final moment was nigh.

The impeachers took stock that night. With five Republican defections seemingly confirmed (Grimes, Fessenden, Trumbull, Fowler, Henderson), the president’s expected vote total stood at 17. He needed only two more. The momentum was definitely in his favor, but maybe he still could be ousted. Maybe Fowler or Henderson could be lured back into the Republican fold. The contest was not over.

The House managers adapted their tactics to the shifting opinions of key senators. Sherman of Ohio and Henderson of Missouri doubted that the Tenure of Office Act applied to Cabinet officers, so they were skeptical of the articles based solely on that statute. That could make it impossible to convict on the first eight impeachment articles. Prospects were even worse for the ninth and tenth articles—the charges based on the president’s consultation with General Emory on February 21, and Butler’s stump-speech article. Those articles were widely disparaged. That left Article XI, the catchall set of accusations sponsored by Thad Stevens. Because of its mix of political charges with alleged crimes under the Tenure of Office Act, Article XI seemed to have the best chance of commanding a two-thirds vote.

On May 7, the managers had decided to propose inverting the articles so the Senate would vote on the last one first. The senators’ speeches on May 11 reinforced this strategy. Senate Republicans agreed that the balloting should start with Article XI. In a countermove, Johnson supporters proposed that the Senate should vote separately on each subpart of Article XI. Chief Justice Chase rejected that motion. The separate allegations in the article, Chase ruled, charged a single high misdemeanor. Stevens no doubt smiled at this vindication of his judgment in assembling Article XI.

As the impeachers braced for the final push, the Johnson forces were optimistic. Charles Woolley sent bullish telegrams on May 11. He proclaimed Johnson’s “stock above par,” and “Impeachment gone higher than a kite.” Collector Smythe was more measured. “Matters look well,” he telegraphed, “though still some doubt.” By the next day, Woolley was again demanding money from Sheridan Shook, Thurlow Weed’s right-hand man. “The five should be had,” Woolley wrote. “May be absolutely necessary.” He also drew $5,000 from a Washington bank, plus another $20,000 from Cincinnati sources. For the big day, Woolley would carry in his pockets the equivalent of $350,000 in current dollars.