Imperial (104 page)

Authors: William T. Vollmann

I can’t help believing in people. There are many who do not know they are fascists but will find out when the time comes.

Amer. Legion has at Brawley emergency committee. On 27 January 1937 they put up the red flags. I have never been cheated out of a dollar in my life.

I can’t help believing in people.

The growers declared that experience had demonstrated that the class of persons found on the “ditch bank” camps are not suitable for field work.

I can’t help believing in people.

I never saw any force. I just stayed away. Of course in the classroom my kids didn’t talk about it.

PART EIGHT

RESERVATIONS

Chapter 105

A DEFINITIVE INTERPRETATION OF THE BLYTHE INTAGLIOS (

ca.

13,000 B.C.-2006)

... there is something unsatisfying about characterizing whole groups of people simply as those who used Clovis-like points . . .

—Robert F. Heizer and Albert B. Elasser, 1980

W

e find in the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo a promise on the part of the United States to restrain and punish

with equal diligence and energy, as if the same incursions were meditated or committed within it’s

[

sic

]

own territory against it’s

[

sic

]

own citizens,

all raids into Mexico by “savage tribes.” This article continues:

It shall not be lawful, under any pretext whatever, for any inhabitant of the United States,

where slavery was of course still legal,

to purchase or acquire any Mexican or any foreigner residing in Mexico, who may have been captured by Indians inhabiting the territory of either of the two Republics; nor to purchase or acquire horses, mules, cattle or property of any kind, stolen within Mexican territory by such Indians.

That this is relevant to Imperial will be proved the very next year, which is to say 1849: Colonel Cave Johnson Couts (we met him long ago in the chapter on syncretic marriages), having just crossed the two-hundred-yard vastness of the Colorado River, confides the following to his journal respecting the Yuma, or “Juma” as he calls them:

They sold Capt. Kane a small girl (prisoner of war) about 10 years of age and whom they had

scalped, accepting in payment a dead horse. (Captain Kane broke the treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, it would seem. I wonder what he did with the child? Probably he meant well.)

There is no doubt of their

Cannibalism.

They are by far the most filthy, miserable, wretched beings that we have ever met or known of. No happiness or pleasure can exist with them unless in the simple absence of

pain.

193

Southside subscribes to some of Northside’s views on the Indian question.

There are educated people in Mexico,

explains a member of that class,

who consider themselves polluted by the mere fact of having to think of the Indian.

194

Who are Indians? As the good citizens of Mexicali say about their Chinese neighbors,

they’re very closed.

No matter: In the perfect treatise I once meant to write, a book entitled

Imperial,

I was going to go at least as deeply into the story of each tribe as I went into the Chinese tunnels. Perhaps I might have even made friends with someone on a reservation or two. Now my money is gone. I have spent more than fifty thousand dollars of my own and other people’s cash on

Imperial.

This section will not and cannot do justice to its subjects. I am sorry.

Who are Indians? They are those whose lands so often fail to be recorded as theirs, and whose names so often fail to be recorded at all. On 7 May 1853, Helena marries Vicente at San Juan Capistrano. Neither one has a surname; the note reads:

Indians.

The same is true of Trinidad and Sylvestre in 1858, of Maria de Jesus in 1856 (her groom, Santiago Gales, was luckier), of Maria Antonia and Pedro in 1857, Catalina and Jose Alejandro de Jesus in 1853 . . .

The 1901 San Diego city and county directory offers us eighteen entries for the locality of Warner, each one an individual’s name except for the first:

Agua Caliente Indians, about 350.

A century later there will be about the same number of Agua Caliente on an eponymous reservation in Riverside County near Palm Springs.

Indians die nameless, in page after page.

A GRASS-GROWN SPIRAL

The Yuma is quiet and docile now,

observed a settler in 1910,

but he does not seem to absorb American civilization rapidly, even when young, and there has been found a most discouraging tendency among the tribesmen to return to their heathenish ways when once the heavy hand of the school-mistress is removed.

A decade later, an educator reports that although it had been

difficult for the Indians to see the advantage of the school training,

which from a between-the-lines reading seems to have been forced upon them, and although

the Yuma are clannish, cling to their own language, and progress

is slow,

nonetheless

the Yuma Indian is considered the best laborer among the Indians and he is on the road to prosperity.

Ninety-two years later, I saw an

Indio

selling newspapers and all-yellow balloons. He was Quechan,

195

he said, meaning Yuman; he must have been on the road to prosperity.

Just north of the line and in sight of the Colorado River, the Quecha Reservation, which occupies 33,613 Imperial County acres, shows off its prosperity of mesas, dunes, scant fields, broken glass, rusted cans, the tank painted with the message

PLEASE REMOVE THIS TANK,

the tan rocks; it is a world made of dried dirt. A long train is breathing and clanking through a cut in the dirt. Prosperity is a bedspring beneath a palo verde tree, a field of green lettuce with red lettuce darkening on one corner of it, abandoned couches, the shell of an adobe building with two walls standing.

In the Yuman creation myth, Wallapais, Mohaves, whites and Mexicans are late-comers.

Some of these held themselves aloof from the other people,

so the Creator, Kwikumat, stamped until fire came, at which the Mexican and the white ran away. Kwikumat’s son and successor

told the whites that if they would enter the darkhouse he would instruct them. But they distrusted him. They were rich and stingy.

I have never been cheated out of a dollar in my life.

I am confident there is a great future for this place,

writes “a Kern citizen who has recently visited Imperial.”

Since being here I have been over lots of country and everywhere I have been are signs of a former vast population of Indians; the country is covered with old pottery and remains of Indian villages,

which proves to him once again that the Colorado River will be as productive as the Nile Delta.

In another issue of this same newspaper we find an illustration of structures which seem to be a cross between giant mushrooms and the grass huts of Africa, with the caption:

INDIAN DWELLINGS ON THE PLAINS NEAR THE IMPERIAL CANAL SYSTEM IN LOWER CALIFORNIA

, meaning Mexico,

WHERE PROVISIONS ARE KEPT TO BE ON TOP OF THE HOUSE INSTEAD OF UNDER IT

.

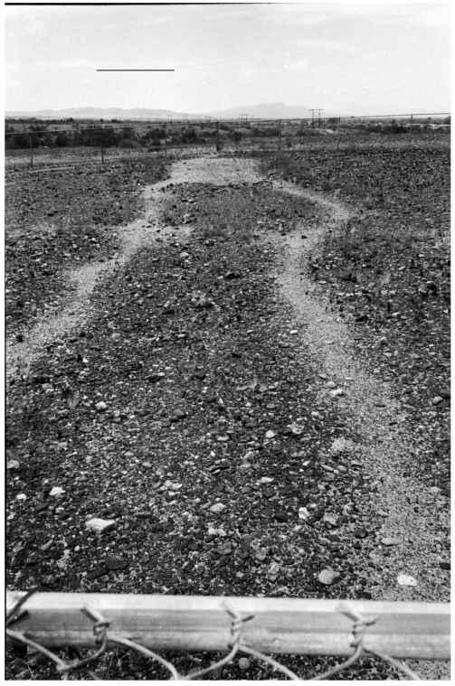

Skeletal debris of human beings have been found in the Yuha Desert near El Centro; they are more than fifteen thousand years old. Who were they? If we entertain no expectations of getting them right, then there is no reason not to imagine them, for our own sake, certainly not for theirs; I myself have experienced the way that the Blythe intaglios, those snaky paths of paleness in the dark brown desert varnish, resolve into figures, some of which are human, at least one of which bears a phallus; I remember an A-shaped figure, not immediately noticeable as human or even artificial except for the straight line of the arm at perpendiculars to the head. The animal and the spiral are much less noticeable, particularly the latter, which has begun to disappear beneath tufts of olive grass. On the first figure are grasses growing at left hand and crotch. They are all fenced in to protect them from a certain subgroup of the victors. Because they may be seen with better understanding from above, I’ve gazed at them from a high mound, where they foreground the glint of a wide bend in the Colorado—yes, nowadays one discovers water instead of water’s tree-lined intimations—then to the southeast, there’s a dark green agricultural checkerboard of considerable size forcing its pale white roads toward convergence; this is the Imperial version of a geoglyph. In the south there goes a pallid grey riverslit, seemingly bottomless, around the gaze to the outlying fields and ranches of Blythe. Beyond those, Imperial offers worn-toothed and fluid-humped swellings of her desert hills.

The Blythe intaglios now constitute a tourist attraction, like Coachella’s Dead Indian Rock near the Palms to Pines Highway, and the Indian fish-weirs west of the Salton Sea, right on the county line. We crush the Indians, then turn them into pixies, hobgoblins, magicians, supernatural figures, so that they are magic or magical expression of the dirt.

South and almost into Blythe, there’s a wide dirt-lined canal, then another. I see a white ranch under huge trees, a row of campers, of palms, then a tawny wall of hay, and more ranches under cool tree-huddles, a third canal.

A bit farther south, the desert preserves kindred inscriptions: for instance, the depictions at Mule Tank. One gets there by means of a winding narrow arroyo whose hot basalt is nearly painful to the touch, and past a ring of dark stones in the sand, in the center of a vast view of vastness, one comes into a great flat-bottomed arroyo, golden and ocher, seeing far away the mountains to the north, and the mountains of Imperial, very blue and cool to the south. In a swirling rocky hole amidst the open golden shadows on the rock are pale red loops, nested circles, waves, infinity signs, insectoid and humanoid figures scratched into the dark shiny rock, and perhaps it would be worth the effort of a lifetime to understand the female figure with golden vegetation lunging below her, sun gilding the top of her shadowed rock; from her, one clambers down past spirals and leaves, sun and white-pebbled pavement.

Anthropologists of American Imperial inform us that the Indians here partake of the Hokan language family,

196

whose mainly extinct representatives existed in several territorial globs upon the California map; for American Imperial we have a long backwards L-shape extending across the bottom of the state and then runningup the eastern edge almost all the way to the beginning of the long diagonal in which Nevada is nested. What do I know of Hokan? To me in my ignorance it’s but another grass-grown spiral.

In the spirit of failure, I accordingly catalogue some of the people of Imperial.

THEY MAKE DOLLS OF DEAD CHILDREN

In the Coachella Valley we find the Cahuillas, and if I were to do them justice I’d at least retell their tale of the Topa Chisera, or Devil Gopher. In the old records of Los Angeles we find some of them among the members of the

Caguillas tribe,

or

Caquillas Indians,

or

mother Indian,

or

parents gentiles of Palluchis tribe,

or

Luiseños.

The word

gentiles

means, of course,

unbaptized.

On 12 January 1853, Maria Encarnacion Esperiaza, born at San Gabriel, receives baptism; she could easily be a few days old, or she could be, as is Maria del Refugio Ysidora,

adult Indian of Caguillas tribe, widow,

sixty years old; as it happens, Maria Encarnacion Esperiaza gets baptized on the first anniversary of her birth. Her mother and her father remain unknown to us, an omission to which the fact that they were

gentiles

is surely relevant. In their stead, the child’s godparents are listed: Jose Gabriel Corillos and Maria Josefa Miranda.

Did I tell you that the Cahuillas fear eclipses, that for them the bear is taboo, that once a year, parents make dolls of their dead children, weep, and then burn them? Shall I insert into the record that both the Cahuilla and the Kamia are renowned for pottery in brown, red and grey? They fashion bladder-shaped vessels decorated with diamonds, spirals and double lines.

The Cahuillas have not had a head-chief since the death of the one they called “Razon,”

meaning, so I read, white man.

197

They have intermarried with the Serrano. Many have become homeless, thanks no doubt to Progress.

They nearly all live upon the large ranches now, doing the roughest and most disagreeable work for small pay. The new era of fruit farming has thrown many of them out of employment . . . The women have no virtue, and many of the males live from the proceeds of a life of shame followed by the females.