Imperial (15 page)

Authors: William T. Vollmann

Of course it comes from the Colorado River, said everyone I asked in Imperial County.

All

water here comes from the Colorado.

22

Mexicans, on the other hand, assured me that the New River began somewhere near San Felipe, which lies a mere two hours south of the border by car. They said that the Río Nuevo had nothing to do with the Colorado River at all.

My plan was to cross into Mexicali, hire a taxi to take me to the source, wherever it was, find a boat, and ride the Río Nuevo downstream as far as I could. But now that I sought to zero in on the mysterious spot (excuse me, señor, but where exactly does it start?), people began to say that the river actually commenced in Mexicali itself, in one of the Parques Industriales, where a certain Xochimilco Lagoon, which in turn derived from Laguna Mexico, defined my Shangri-la. How could I take the cruise? Moreover, the municipal authorities of Mexicali were even now pressing on into the fifth year of a very fine project—namely, to entomb and forget the Río Nuevo, sealing it off underground beneath a cement wall in the median strip of the new highway, whose name happened to be Boulevard Río Nuevo and which was a hot white double ribbon of street adorned by dirt and tires, an upended car, broken things. Along this median they’d sunk segments of a long, long concrete tube which lay inconspicuous in the dirt; and between some of these segments were gratings, sometimes lifted, and beneath

them

lay square pits, with jet-black water flowing below, exuding a fierce sewer stench which could almost be some kind of cheese—yes, cheese and death, for actually it smelled like the bones in the catacombs of Paris.

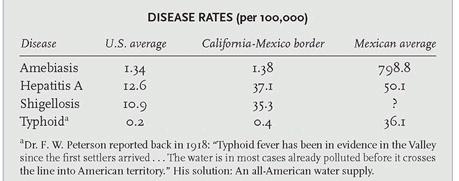

What were some of the treasures which the Río Nuevo might be carrying to the United States today? The following chart encourages an inventory:

Source:

Environmental Protection Agency.

A yellow truck sat roaring as its sewer hose, dangling deep down into the Río Nuevo, sucked up a measure of the effluvium of eight hundred thousand people. This liquid, called by the locals

aguas negras,

would be used in concrete mixing. Beside the truck were two wise shade-loungers in white-dusted boots, baseball caps and sunglasses. I asked what was the most interesting thing they could tell me about the Río Nuevo, and they thought for awhile and finally said that they’d seen a dead body in it last Saturday. The one who was the supervisor, Señor José Rigoberto Cruz Córdoba, explained that the purpose of this concrete shield was to end the old practice of spewing untreated sewage into the river, and maybe he even believed this; maybe it was even true. The assistant engineer whom I interviewed at the civic center a week later said that they’d already found hundreds of clandestine pipes which they were sealing off. He was very plausible, even though he, like so many others, sent me far wrong on my search for the headwaters of the New River. Well, why wouldn’t the authorities seal off those pipes? My interpreter for that day, a man who like most Mexicans declined to pulse with idealism about civic life, interpreted the policy thus: See, they know who the big polluters are. They’re all American companies or else Mexican millionaires. They’ll just go to them and say, we’ve closed off your pipe. You can either pay us and we’ll make you another opening right now, or else you’re going to have to do it yourself with jackhammers and risk a much higher fine . . .—No doubt he was right. The clandestine pipes would soon be better hidden than ever, and subterranean spillways could vomit new poisons.

23

The generator ran and the Río Nuevo stank. The yellow truck was almost full. Smiling pleasantly, Señor Córdoba remarked: I heard that people used to fish and swim and bathe here thirty years ago.

Perhaps even thirty years ago the river hadn’t been quite so nice as he said, or perhaps people had fewer opportunities back then to be particular about where they bathed; for that night, in a taxi stand right in sight of the river, while a squat, very Indian-looking dispatcher lady in a sporty sweatshirt sat shouting into a box the size of a microwave, with the radio crackling like popcorn while the drivers sat at picnic tables under a sheetmetal awning, the old-timers told me how it had been twenty-five years ago. They’d always called it the Río Conca, which was short for the Río con Cagada, the River with Shit. Twenty-five years ago, the water level was lower because there’d been fewer irrigation canals to feed the watercourse, and the drivers used to play soccer here. When they saw turds floating by, they just laughed and jumped over them. The turds had floated like

tortugas,

they said, like turtles; and indeed they used to see real turtles here twenty-five years ago. Now they saw no animals at all.

Where does most of the sewage come from? I asked Señor Córdoba.

From the factories and from clandestine pollutants. It’s a good thing that we’re making this tube, so that now it’ll just be natural sewage.

After the first hour on Boulevard Río Nuevo, I began to get a sore throat. The two sisters who were interpreting for me felt nauseous. After the second hour, so did I. (Maybe this wasn’t entirely the Río Nuevo’s fault; the temperature that day was a hundred and fourteen degrees.) Even now as I write this I can smell that stench. Well, in another year or two it would be out of mind—in Mexico, at least. I remember coming back near that place at twilight, and finding a sepulchershaped opening between highway lanes, a crypt attended by a single pale green weed, with the cheesey shit-smell rising from that greenish-black water which sucked like waves or tides. More concrete whale-ribs lay ready in the dust; soon this memory-hole also would be sealed. The assistant engineer at Centro Cívico said that his colleagues hoped to bury five point six kilometers more by the end of the year . . .

CALL IT GREEN

The taxi driver followed the Río Nuevo as well as he could. Sometimes the street was fenced off for construction, and sometimes the river ran mysteriously underground, but he always found it again. We could always smell it before we could see it. Now it disappeared again, beneath a wilderness of PEMEX gas stations. At Xochimilco Lagoon, liquid was coming out of pipes and foaming into the sickly greenness between tamarisk trees. The water didn’t just stink; it reeked. Then it vanished into a culvert. Old men told me how clear it used to be twenty years ago. Thirty years past, people swam in it. Oh, yes, the Río Nuevo kept getting better and better in retrospect. At Mexico Lagoon the sight and the tale were much the same as at Xochimilco.

The end, said the taxi driver, smiling with pride in his English.

That, so I thought, was all of the Río Nuevo I could ever see except for the federal zone where in a gulley overlooked by low yellow houses, white houses and dirt-colored house-cubes (this gulley dated back a century ago, when the Colorado made the Salton Sea), the northernmost extremity of the river had been fenced off from the public and by the same logic allowed to run stinkingly free; the water was here very green.

A digression on greenness: A block or two up the western gulleyside, which is to say on the poor-hill which could be seen from the street by the Thirteen Negro dance hall, a legless man named Señor Ramón Flores was sitting in the porch-shade of his little yellow house on Michoacán Avenue. He used to be a taxi driver; another driver remarked that diabetes had done for his legs.—I’ve been here since 1937, he said. I’ve always lived in this house. I remember the Río Nuevo.—Raising his hands like a conductor, outstretching his fingers like rain, he sighed happily: It’s

always

been green! There were

cachanillas

and tule plants. They were all over the Río Nuevo, but they’re not there anymore. And I remember how in 1952 the river overflowed. People were camping around it then, in Colonia Pueblo Nuevo. The gringos threw water into the river on purpose so that people would get out of the area. So the government moved them from Colonia Pueblo Nuevo to Colonia Baja California . . .

So the

cachanillas

and the tule plants are gone, you said. How about the smell? Does it smell any worse than it used to?

Oh, it’s always smelled that way, but in the summer it’s worse. Have some more mescal. You know, down south there’s another kind of mescal that’s stronger. Three shots and you’re in ecstasy; three shots will knock you out.

Thanks, Señor Flores, I will, and we enjoyed a long slow conversation on the subject of exactly why it was that Chinese food in Mexicali tasted different from Chinese food in Tijuana—it had to do with the

chiltepín

sauce—until the hot evening breeze sent another whiff of Río Nuevo my way, prompting me to inquire: Do you have any problems with the smell? Does it ever make you sick?

We’re used to it, he said proudly.

Does it always smell like sewage, or is there sometimes a chemical smell?

No, it just smells like shit.

Do you think it’s justice for the gringos that you send your sewage to America?

They asked for it, he laughed. They use it for fertilizer.

A Border Patrolman told me that the Río Nuevo will strip paint off metal. Do you think that’s true or is it just propaganda?

Oh, that’s true, he said contentedly.

Yes, the water was very green, no matter that an elegant woman in leopard-skin pants who’d lived beside the river for twenty years in the slum called Condominios Montealbán shook her long dark hair and said: Green? No green. No brown, no black. No color. Just dirty.—White foam-clots drifted down its surface as tranquilly as lamb’s fleece clouds, but it was green, call it green, and green trees attended it right to the rusty border wall, where as I stood gazing at the river one of the two Hernández sisters pointed in the other direction; and between a painting of the Trinity and a gilded tire from which other

pollos

began their illegal leap, half a dozen young men came running from a graffiti’d building to swarm up over the wall, forming that graceful human snake I had come to know so well, the first man being lifted over by the last, all of them linked, then the ones who were already over pulling the last ones over and down into the Northside, while Susana, the gentle sickly one, watched sadly from the taxi, and the other, Rebeca the dance choregrapher, crossed herself and said a prayer for them.

THE NATURAL SPRINGS

But

nobody

seemed to know where the New River came from. Mr. Jose Angel, Branch Chief of the Regional Water Control Board up in Palm Desert, seemed to think the source to be some sixteen miles

south

of Mexicali, he didn’t exactly know the place.

Fitting his fingertips together, the assistant engineer at Centro Cívico mentioned “natural springs.” He drew me a map which located these springs on the side of a squarish volcano called Cerro Prieto, which was located due

west

of Mexicali on the Tijuana road. A drain then carried the natural springs’ contribution to civilization meanderingly southwest and then southeast to Laguna México, which as I’ve said drained into Laguna Xochimilco. My driver for that day accordingly sped me almost to Tecate before we found out that actually Cerro Prieto was due south of Mexicali, and not sixteen miles as Jose Angel had said but sixteen kilometers, so we careened back to take a southward turn on the San Felipe road, crossing the Río Nuevo once at five point two kilometers; and we kept faithfully on across the Colorado delta sands until from the direction of the broad purple volcano there came a faint but mucilaginous stink.

At the very beginning of the twentieth century, pioneer-farmers on the American side used to frequently see Cerro Prieto

thrown up by the mirage into the form of a battleship showing plainly the masts and turrets.

The woman who wrote down this recollection in 1931 added that such mirages were much rarer now,

because of the amount of land under present cultivation.

In 2001, Cerro Prieto sometimes grew quite indistinct, thanks to those clouds of commerce—well, well, Imperial’s not about beauty after all; it’s about money and need. Near the town of Nuevo León, trailers and gates marked out the restricted geothermal station; and in a certain air-conditioned office, an engineer looked up from the blueprints on his glass-topped table and said: As far as I know, it has no connection with the Colorado River.

It was true that no direct connection existed, not anymore.

In an undated map, hand done on grimy linen, which when unrolled takes an entire wide library table, we see all the California Development Company’s canals in Mexico—the

former

California Development Company, I should say, for the map is entitled “Northern Part of the Colorado River Delta in Lower California, Compiled by California Development Company, W.H. Holabird, Receiver.” (Receivership occurred in about 1910, once the California Development Company went bankrupt thanks to the Salton Sea accident.) The canals have been not only drawn, but tabulated with their lengths, the longest of these being the Alamo River (fifty-six miles), which evidently has been thoroughly tamed into a canal by or in the mind of the California Development Company. Then come fifty-two-odd miles of lesser arteries and drainages. The New River for its part swarms north by northwest from an immense blue Laguna de los Volcanes

24

in the neighborhood of Cerro Prieto. Accompanying the yellow-watercolored Volcano Lake Levee, it presently enters the New River Basin, which thanks to that accident has grown vaster than Calexico and Mexicali combined. And in this zone, which is not too far south of the border, we discover the largish colored square of the Packard Tract, which the West Side Main Canal diagonally bisects.