Imperial (151 page)

Authors: William T. Vollmann

Do many people want your job? I asked him.

Every time they do my job, they quit, ’cause no one can stand my supervisor. I been there three years so maybe I’ll make plans to change my job . . .

We’ve been struggling for two months now, he went on. Sometimes they pay us; sometimes they don’t. Last week they were about three days late. So we went on strike. They kept paying the supervisors. Some of us were with the strikers. Some of us were with

them.

I come out at three-thirty. Sometimes they want me to do a double shift, but I say no, he proudly announced.

His

novia

worked at Sony, where conditions were better, so he thought. But possibly she wasn’t his

novia

anymore; it sounded as if he had love problems.

He was born in Michoacán, and came to Tijuana only because the Americans deported him from Fresno, where he’d spent twelve illegal years, the crossing paid for by his mother. He ended up in prison for driving without a license and driving while intoxicated, which was how he caught the attention of our Immigration Department. It had been four years now since his forcible return. They’d put him across at San Ysidro, so the first thing he did was visit his cousin here in TJ. Then he stayed with his aunt, and eventually bought land from her. Now here he was; he’d achieved the Great Mexican Dream; he toiled in a

maquiladora.

The second time I met him, I noticed his scar.

He’d been making razors for Dorusa in La Presa, his first job, and suddenly razors came shooting out of the machine into his arm; he admitted that he hadn’t been carefully watching.—They took me to the hospital, Salvador told me. They said it wasn’t that bad. If you get a lawyer, the lawyer charges you money. People don’t like to argue with a

maquiladora.

You win this much, and they only pay you half.

No gloves or else the machine will take your fingers off; that had been the rule at Dorusa.—Some guy lost his finger; I saw it, said Salvador. He was using gloves, and the machine got his finger and half his other finger. When we stopped the machines we saw his finger in there . . .

THE PRICE OF A MASK

Like most human records, this account essentially recounts failure; and we never did get button-camera footage of the interior of Óptica Sola; I remember parking yet again in front of Metales y Derivados with the black plastic blowing and us both getting headaches after a moment or two and then Terrie’s eyes began to sting. Perla rushed jauntily off, while across the street two men carried an enormous crate on their shoulders into a dark well of barrel-shaped containers. One wore a white mask and a shield. Why not both? The wind blew from Metales y Derivados, and I began to get a sore throat, although only slightly. That sour-salty smell of something poisonous was in my nose and mouth; it was blowing right into the loading dock where those men lifted crates. I remembered that terrifying science-fiction novel

On the Beach,

when the entire world perished bit by bit from silent radioactive contamination; one couldn’t feel it right away, one character explained to another, but I’ve already got it and you’ve got it and the baby’s got it.—The flapping tarps and stinking wind were very disturbing. Needless to say, those two men from Rimsa who were supposed to be cleaning up the place had done nothing; at least they weren’t sitting on the ground eating more lead sandwiches today. It was three-twenty; halfway down the block, blue buses pulled up in front of Óptica Sola; this shift must get out at three-thirty; then Perla returned, shaking her head and laughing:

Nada!

The guard had denied her entrance since there was no work to spare. She then bravely tried to walk through the open door into the production line, at which point another guard called her over and reiterated that they weren’t hiring women right now.

My self-disappointment at failing to enter that immense fortress has since been mitigated by an article I read in the newspaper

El Sol de Tijuana,

a sweet little story, in fact a charming story:

A large mobilization of emergency crews was provoked by the spill of a non-toxic but extremely flammable chemical inside a factory, where 80 workers were forced outside and a security supervisor detained for preventing entry of firemen.

The event occurred at 10:30 yesterday at Óptica Solare

286

on Insurgentes Blvd. . . .

The questionable part of the event was that the spill of perchloride happened at 8 am and was not reported by the owners in order to not “alarm the workers,” but area residents reported it to the fire chief.

When the firemen arrived at the plant they found the entry locked with a chain and padlock, and the security guard refused to let them enter. They had to wait for the police to arrive, enter by force, and detain the guard.

The firemen then entered and rescued the 89 workers, some of them with vomiting, nausea, and dizziness, in the paramedic’s opinion all psychological, since the spilled chemical was not a mortal danger to health.

But since a conflagration could start at any moment since it is highly flammable when exposed to heat, the police proceeded to cordon off the area and prohibit entry.

In the opinion of the assistant fire chief, the executives at Óptica Solare made a grave

error in blocking entry and in keeping the workers inside working. He estimated it would take several hours to make the air breathable because of the poor handling of the chemical in a space with no ventilation . . .

So if even firemen can’t get into Óptica Sola when the place is in imminent danger of bursting into flames, why should this second-rate investigative journalist feel humiliated that he, too, was foiled?

Off we sped to Formosa Prosonic, happily unaware that Perla’s videotaping there would prove as useless as it was going to be unpleasant. Out by the Playas the pale ocher earth cut away again; past the new Mormon church (count on Terrie to notice each one of those, and now I know her secret: no cross on the steeple), a few houses huddled in the dirt; by then we were coming up to Plaza de Cumbres on its hill of sand and earth; we were right up on the summit with the Pacific below and on the right a triple-stranded barbed wire fence. The blue-and-white-striped factoryscape of Formosa beguiled us, right next to Fluidmaster Mexico-Maquiladora, whose representative had been either busy or away, I forget which, when Terrie had called to request an appointment.

We parked around the corner from Formosa’s main gate, but it was still Formosa. A big pipe ran down the bare hillside. I couldn’t see where it started. Señor A.’s theory that many of these

maquiladoras

excreted untreated poisons into the earth through such vessels had come to seem unerringly plausible; it would certainly be an explanation for the smell. Of course the degree, if any, to which Formosa emits dangerous chemicals into its surroundings remains unknown to me. I lacked the budget to take soil and water samples as I had done when researching the Salton Sea and the Río Nuevo; besides, as you remember, the results of those latter tests cannot be called dramatic.

So what can I tell you about these factories? The social responsibility of at least one

maquiladora

may be gauged from the following cassette tape, which I have in my possession, and which is the record of a telephone call made to Thomson, which Señor A. claimed to be the worst or one of the worst polluters. The caller (Perla, I suspect) is pretending to be one of the factory’s neighbors:

Every night we have to deal with a really bad smell, says the woman. It smells like something burning. My kids are getting sick.

Well, replies Thomson, if your kids have allergies, it’s not our problem.

I don’t know what to do; I can’t help you, the Thomson woman keeps saying. Finally she comes up with the ideal solution: I’ll have you talk to someone else.

A man comes on the line.

There are toxic fumes coming from behind your factory and it’s affecting our children, the woman repeats. Their throats and eyes hurt. Can’t you do anything to control the smoke?

I’m not really in charge of the smoke but I can call you back, says the man. What’s your number?

She gives him one which is no doubt invented.

We don’t have any harmful toxic fumes, he reassures her.

What about the smoke?

Oh, is there smoke coming out from behind our factory? asks the man in surprise, and it is all one can do not to laugh or maybe curse; in Señor A.’s video of Thomson one can see the black, black smoke . . .

Meanwhile, behind that graffiti’d fence, before the wall of pipes, Formosa’s workers hauled long flexible strips of metal, two workers per strip, and they laid them carefully side by side in the dirt. My eyes began to sting.

Now we waited for the flatvoiced girl with glasses to come; she worked at Fluidmaster now, from six-thirty in the morning to three-twenty in the afternoon; she had only two fifteen-minute breaks.

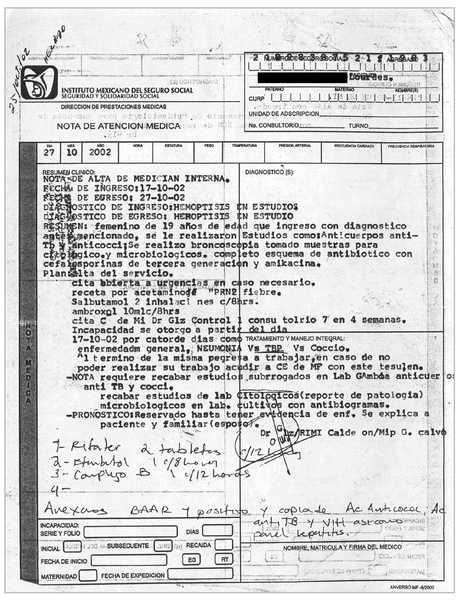

The fat, flatvoiced girl with glasses was named Lourdes. Before I met the girl, I’d already met her chest X-rays and her case file,

NOTA DE ATENCIÓN MÉDICA

, dated 27102002, for

A—————

(

PATERNO

)

B—————

(

MATERNO

)

Lourdes

(

NOMBRES

). There was something ugly about her personality, I thought. Terrie didn’t think so; Terrie thought her brave and she was, but her bravery came from some bitter, brutalized place; I felt disliked and suspected by her. I sometimes have the same feeling when I interview a rape victim.

We were sitting in the car in La Jolla Industrial Park. Terrie and Perla were wiring Lourdes up for another button camera which was going to fail, and when Lourdes came out of Fluidmaster the security guard seemed to be searching her body, at which point I was almost ready to vomit for anxiety; my rule in these adventures was to take full responsibility for the people working for me, and I was wondering how I was going to get Lourdes out of this and what would happen to me, when she waved cheerfully to the security guard and strolled back to the car; that is what I mean when I say that she was brave.

I asked what had happened to her at Formosa and she said wearily: I got pneumonia and also tuberculosis. I assembled radio speakers.

Why did you get sick?

Because of the glue, which had toxic chemicals in it.

How do you know it was from the glue?

Because it was what everyone was breathing in all the time.

And what did the glue smell like?

I’m not sure how to say it, but it was strong and ugly. It burns the throat.

When you’re coming to work at Fluidmaster, can you smell it?

Sometimes but not really.

Lourdes’s medical chart. She believed that her symptoms resulted from her work in a

maquiladora

.

How many years did you work at Formosa?

Two years eight months.

When you brought in the X-rays, what did they say?

They didn’t care. They sent me some insurance.

And how are you feeling now?

Okay. I had a treatment. Pills and a spray.

(When I asked Perla whether Lourdes’s health had been ruined permanently, she answered: It has not improved. She still has a cough.—That was what Perla said, although during the hour or so I spent with Lourdes, she never coughed. I suppose it is possible that she coughs at night.—Did Formosa’s glue injure her? How can I say?)

Are the

maquiladoras

good or bad for Mexico?

Well, said Lourdes, more or less, the thing is—we have to work.

So they’re good?

More or less, she said in what I believe to have been quiet fury.

Can you tell me what happened after the doctor X-rayed you?

I went back to work after getting better and got sick all over again.

I’ve already told you that in the coarse yellow-brown envelopes of the Instituto Mexicano del Seguro Social lay those two X-rays, dated October 2002, which Perla claimed show pneumonia and which I photographed; I have not yet had a doctor look at my negative, and even if pneumonia can be proven, I see no further proof that the glue at Formosa either caused or exacerbated Lourdes’s pneumonia. But here is one thing that somebody at Formosa ought to get barbequed in hell for, if what Perla and Lourdes both told me happened next did happen: When Lourdes recovered and returned, she asked Formosa to give her a mask, and Formosa refused.

That was why she quit, because she didn’t wish to continue getting sick. She said that they gave her two hundred and fifty dollars as a settlement to keep her from suing them.

287

And how is it now, working at Fluidmaster?

It’s really good. I do a lot of work with my hands. I sit at a table. It’s comfortable. I sit and pack. What we make is the floating thing inside the toilet . . .

WINDOWS OF DARKNESS, JELLYFISHES OF LIGHT