Imperial (3 page)

Authors: William T. Vollmann

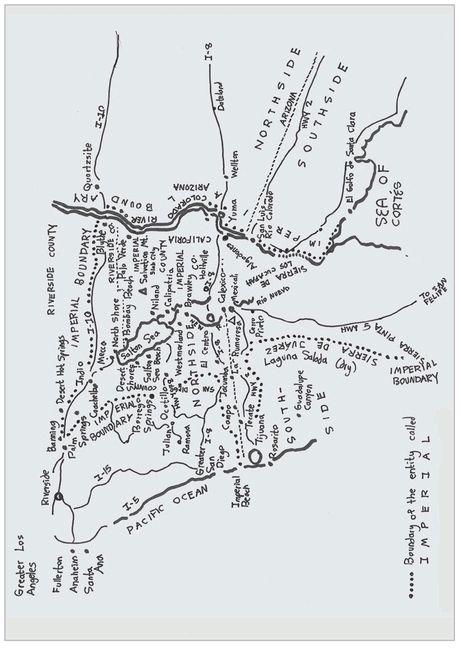

The Entity Called Imperial

Closeup of Imperial

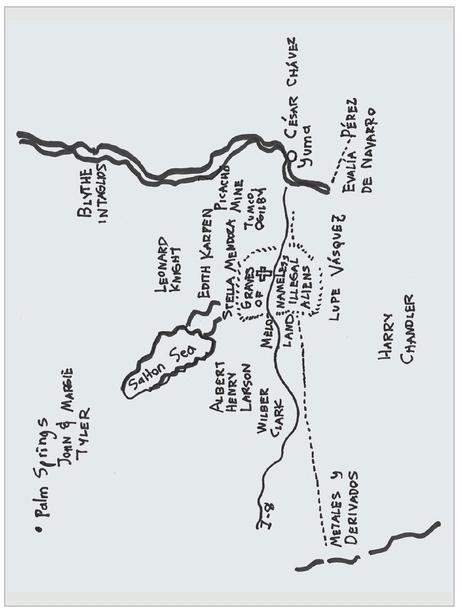

Persons and Places in Imperial

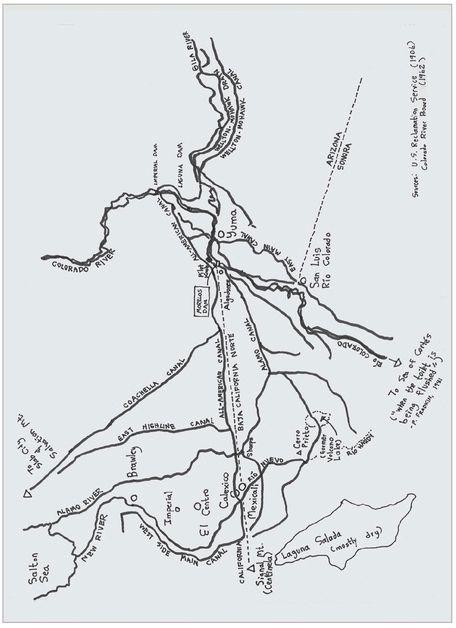

Rivers and Canals in Imperial

BRIEF GLOSSARY

The following terms are of considerable importance in what follows. Readers unfamiliar with Mexico or the Spanish language may not know them, as when beginning my research I certainly did not. Although they get defined in situ, they might as well be given all together here.

Acre-foot—The amount of water needed to cover an acre one foot deep. One acre-foot = 1,233.5 cubic meters = 326,000 gallons.

Campesino—Literally, “country person.” Now a term used, with varying degrees of vagueness, to describe all tillers of the soil in Mexico. (Field workers employed in the United States are often excluded.) This encomium of commonality might have been first used by Catholic reformers shortly after the Mexican Revolution (1911). Before that, hacienda day laborers, indigenous inhabitants of pueblos, small-scale landowners, sharecroppers and former possessors of land reduced to vagabondage could well have seen one another simply as “other.” The word quickly established a connotation of leftist militancy not much to the taste of the Catholic Church.

Colonia

—Settlements of a less corporate character than

ejidos.

The residents can buy and own parcels, and sell them.

Coyote—See

pollo.

Ejido

—Communal inalienable holdings, either from pre-Conquest times or else carved out of other lands by the Mexican Revolution.

Field worker—Somebody, in our context usually a Mexican, who labors in the fields of others, usually Americans. The words “campesinos” and “field workers” are often interchanged when speaking of the brownskinned people one sees stooping and sweating in the Imperial Valley. Acccording to the bargirl Emily at the Thirteen Negro dance hall in Mexicali, which is patronized by both groups, campesinos stay in Mexico, while field workers cross the line and do about fifty dollars a month

1

better.

Fracción

—A newer

colonia.

Golondrina

—Literally, a swallow (the bird, not what the throat does). Also, Southside slang for a fly-by-night

maquiladora

which shuts down without paying its workers.

Guía

—A nice name for a

coyote.

Hacienda—A plantation farm. Famous for gobbling up

ejido

lands. Very powerful under the Díaz regime. The Revolution of 1911 began to break up the haciendas.

Hectare—Generally employed in Southside in place of the acre. One hectare = 2.47 acres.

Maquiladora

—A foreign-owned factory in Mexico, usually somewhere near the border. Pronounced with a single

l,

not a double, which would make it sound like something to do with makeup.

Northside—The United States.

Pollo

—Someone who tries to cross the border illegally. Often guided by someone who is derogatorily referred to as a

coyote.

(A.k.a. pollista

or

pollero.)

Pueblo—A long-standing communal holding (often a village or town). Less formal a designation than

ejido,

and less tied to specifically agricultural land.

Rancho—A small private landholding. The owners were rancheros. Sometimes they allied themselves with the

campesinos;

occasionally, with the

hacienda

owners.

Solo

—A person who attempts to cross the border illegally and alone.

Southside—Mexico. (“Northside” and “Southside” are employed mostly by the Border Patrol. I have appropriated them for my own purposes.)

PART ONE

INTRODUCTIONS

Chapter 1

THE GARDENS OF PARADISE (1999)

I think we all feel sorry for ’em.

—Border Patrol Officer Gloria I. Chavez, on the subject of illegal aliens

BODY-SNATCHERS

The All-American Canal was now dark black with phosphorescent streaks where the border’s eyes stained it with yellow tears.—These lights have been up for about two years, Officer Dan Murray said. Before that, it was generators. Before that, it was pitch black.

He was an older man, getting big in the waist, whose face had been hardened by knowledge into something legendary. For years he’d played his part in the work first begun by Eden’s angel with the flaming sword, the methodical patrols and prowls to keep the have-not millions out of paradise—which in this case was Imperial County, California, whose fields of blondeness, of endless pallid asparagus, onion plants like great lollipops and honey-colored hay bales produced the lowest median tax income of any county in the state. Zone El Centro, named after the county seat, comprised Sectors 210 to 226, of which Sectors 217 to 223 happened to be Murray’s responsibility. He kept the key to the armory, whose rows of M4 shotguns awaited a mass assault from Southside which never came. He knew how to deploy the stinger spikes, the rows of accordion-like grids like a row of caltrops: Pull a string and they opened up to puncture a tire. One car actually drove twelve desperate miles on four flat tires until it was wrecked beyond any conceivable utility to its confiscators.

They’ll pop their heads up in a minute, he was always saying. He was always right.

An hour ago we might have been able to see through the bamboo and across the wrinkled brown water into Southside where Mexicans sat on the levee waiting to seize their chance, but at that time Murray and I had been over by the Port of Entry East bridge where two Mexicans waited, not aliens yet; while on our side, Northside, another agent sat calmly watching them in his car.

Hello, said Murray. Have those folks been there all day?

Yessir, the agent said.

Suddenly it was dusk, and the two men were already crossing. Now they were illegals.

Get out!

an officer yelled at them. They turned and slowly, slowly walked back into Mexico across the humming throbbing bridge.

Then we drove west down the long horizon of border wall. Two Mexicans walked along the fence down in Southside, screaming obscenities at Murray.

Now, you see, this has got concrete, Murray explained. But it only goes down about four feet. They have their little spider holes. They pop up, throw a rock through the windshield, then go down again.

We drove west, down into the lights of Calexico and out again, passing the sandy waste whose incarnation as a golf course was memorialized by carcasses of palm trees.—See, another hole in the fence back there, Murray said. Usually you just hold back and wait. They’ll pop up.—The golf course had gotten robbed once too often, and then somebody burned down the clubhouse after a fence-jumper from Southside was shot. So some townspeople told me. Their stories were weary and muddled, but in them as in this former golf course the border wall remained ever in the background, its long, rust-colored fence dwindling into lights. Then the dim red fence abruptly ended, and we met the All-American Canal, which comprises so much of this sector’s border westward of the wall. Follow the All-American upstream on a map, and you’ll see that it abruptly turns north, wraps around Calexico International Airport near that abandoned golf course (the hollow in this spot is a good place for

pollos

and

solos

to hide, and sometimes for bandits, too, who murdered somebody here half a year ago), and then it bends due east again just before Comacho Road, ducking under the railway and Imperial Avenue, streaming on eastward toward its source, until the last we see of it, it’s overlined the streets named after southwestern riches: Turquoise Street, Sapphire Street, Garnet Street, Ruby Court, Emerald Way, Topaz Court—after which it runs off the map and out of Calexico. In the first four months of 1999 alone, eight people whom the authorities knew of had already drowned in the All-American’s cool quick current, all of them presumably seekers of illegal self-improvement; and I imagine that other bodies were never found, being carried into jurisdictions where perhaps the non-human coyotes got them. In April 1999 the United States Navy began to wire the canal with a two-hundred-thousand-dollar noise-detection apparatus.—

The goal is to create a system that can alert authorities when someone is in trouble in the canal,

my home newspaper informed me blandly. Who am I to doubt the Navy’s altruism?

You should see these guys pickin’ watermelon, bent over all day, said Officer Murray. They do work most Americans wouldn’t do.

We were close by the Wistaria Check, which lay opposite the place on the Mexican side where the taxi driver and Juan the cokehead had taken me the day before. The taxi driver had said: If you want, I’ll jump into the canal and swim across, if you pay me.

Juan, whose scrawny back and shoulders most proudly bore a tattoo of the Virgin for which he’d paid two U.S. dollars back when he was twenty (he was now Christ’s age), stopped the taxi to buy five hundred pesos’ worth of powder in a twist of plastic. He was a true addict. Every day I had to advance him his wages. By late afternoon he needed a bonus. I had found him amidst the slow round of beggars and drunks on a street two blocks south of the United States where a poster announcing a

MILLION DOLLAR FINANCIAL SERVICE

depicted a giant identification card which among all its elysian proclamations faintly whispered NOT A GOVERNMENT DOCUMENT, then rushed on to proclaim

ORDER YOUR PERSONAL U.S. I.D. CARD HERE TODAY

. On that hot afternoon when we departed Mexicali’s red and yellow storefronts and drove westward into the dirt, the houses shrinking into shacks, Juan and the taxi driver kept glancing at me and muttering together; but I told them that I would have even more cash when I came back tomorrow. Far away, deeper into Mexico, I could see the pale bluish-white mountains like concretions of dust. Now we came into Juan’s hometown where several of the Mexicali street-whores lived, and although Juan wanted to stop to buy more coke, business, personified by me, demanded that we leave behind those long blocks of tiny houses of cracked dry mud whose yards were dirt instead of grass. So we turned onto a long dirt road in parallel to the All-American Canal, which we could not yet see. Here each of the many tiny cement or adobe houses was fenced away from the world. One fence derived from boxspring bed-frames. Other fencepoles had been fashioned of twigs or columns of tires, and there were many hedges of thorns on that nameless road of prickly pears, bamboo, dust, beautiful palm trees, and turtles sleepily lurking in the stagnant ditch-water.