Imperial Requiem: Four Royal Women and the Fall of the Age of Empires (41 page)

Read Imperial Requiem: Four Royal Women and the Fall of the Age of Empires Online

Authors: Justin C. Vovk

After four days of lying in state in the Throne Room of Buckingham Palace, Edward VII’s large oak coffin was ceremoniously taken to Westminster Hall for the funeral. Held on May 20, 1910, the funeral for King Edward VII brought together the largest group of royals in history up until that time.

606

One of the first people to arrive in Britain was the widowed Queen Alexandra’s sister Empress Marie Feodorovna. Attending the funeral was the new king, along with eight other reigning monarchs, all of whom were directly related to Edward in some way. There was his nephew Emperor Wilhelm II; his brothers-in-law the kings Frederick VIII of Denmark and George I of Greece; his nephew and son-in-law King Haakon VII of Norway; King Alfonso XIII of Spain, a nephew by marriage; and his second cousins the kings Ferdinand I of the Bulgarians, Manoel II of Portugal, and Albert I of the Belgians. Beyond these nine reigning monarchs were also seven queens, seven crown princes, thirty princes and heirs, and royals representing Turkey, Austria, Japan, Russia, Italy, Romania, Germany, Sweden, the Netherlands, Montenegro, Serbia, France, Egypt, and Siam. According to one historian, “who, seeing this self-confident parade of royalty through the streets of the world’s greatest metropolis on the occasion of Edward VII’s funeral, could imagine that their future was anything but assured.”

607

The funeral was a pageant lifted from the pages of history. England had never seen a funeral on such a scale before, and it would not see anything like it again until the death of Diana, Princess of Wales, in 1997. The procession made its way from Buckingham Palace to Westminster Abbey. More than two million hushed onlookers watched the awe-inspiring sight of the nine reigning monarchs, dressed in gold-braided uniforms with plumed hats and resplendent medals, riding three by three behind the funeral cortege. Behind this grand display “came five heirs apparent, forty more imperial or royal highnesses, seven queens—four dowager and three regnant—and a scattering of special ambassadors from uncrowned countries.”

608

Writing to Nicholas II, Minnie said the funeral was “beautifully arranged, all in perfect order, very touching and solemn. Poor Aunt Alix [Queen Alexandra] bore up wonderfully to the last. Georgie, too, behaved so well and with such calm.”

609

The legacy of King Edward VII was a profound one. The echoes of his reign would carry Europe forward as it marched headlong toward the summer of 1914. Thanks to Edward VII’s efforts, Queen Mary and King George now occupied a throne that was stronger than it had been at Queen Victoria’s death and was more respected than ever. Edward was also a talented diplomat. His easygoing, gregarious nature won over even his staunchest of critics. The Italian foreign minister remarked that he had been the most powerful personal factor in world diplomacy. Not only did he forge alliances with France and Russia, he also strengthened the ties between the British crown and its counterparts among the continent’s royals through their shared bonds of family.

Edward … was often called the “Uncle of Europe,” a title which, insofar as Europe’s ruling houses were meant, could be taken literally. He was the uncle not only of Kaiser Wilhelm but also, through his wife’s sister, the Dowager Empress Marie of Russia, of Czar Nicholas II. His own niece Alix was the Czarina; his daughter Maud was Queen of Norway; another niece, Ena, was Queen of Spain; a third niece, Marie, was soon to be Queen of Rumania. The Danish family of his wife, besides occupying the throne of Denmark, had mothered the Czar of Russia and supplied kings to Greece and Norway. Other relatives, the progeny at various removes of Queen Victoria’s nine sons and daughters, were scattered in abundance throughout the courts of Europe.

610

This far-reaching influence was what King Edward VII bequeathed his son and daughter-in-law upon his deathbed. It was now up to King George V and Queen Mary to carry the torch that Edward VII had lit during his lifetime into the twentieth century.

Once the funeral was over, it did not take long for discord to seize the royal family. To Mary’s disappointment, George’s sister Toria was becoming possessive of the king and critical of her. “Do try to talk to May at dinner,” Toria told a guest during a party, “though one knows she is deadly dull.”

611

The real struggle, though, was with her mother-in-law, Alexandra, the queen dowager, who at first refused to relinquish her position as first lady of the land and “quibbled about questions of precedence.”

612

In a total break with tradition, Alexandra demanded precedence over Mary, which she only gave after being harangued by her mother-in-law for weeks. “I am now very tired after the strain of the past weeks & now as you know come all the disagreeables,” Mary wrote to Aunt Augusta, “so much to arrange, so much that must be changed, most awkward & unpleasant for both sides, if only things can be managed without having rows, but it is difficult to get a certain person [Alexandra] to see things in their right light.” Alexandra had to be practically forced to vacate Buckingham Palace and return to her old home, Marlborough House. She was unwilling to give up many of the crown jewels that were now rightfully Mary’s. “The odd part,” Mary wrote to Augusta, “is that the person causing the delay and trouble remains supremely unconscious to the inconvenience it is causing, such a funny state of things & everyone seems afraid to speak.”

613

There were undeniable shadows of the tumultuous relationship between Alexandra of Russia and the fiery, stubborn Marie Feodorovna. As Mary’s lifelong supporter, Grand Duchess Augusta placed the blame for this rift between Mary and Alexandra squarely on Minnie’s shoulders, a woman who had become used to remaining in the public image during her widowhood. One of the dowager empress’s biographers felt the problem was that, since Alexander III’s death, she became “used to the prestige and influence of a Dowager Empress and she could not (or would not) understand that in England things were very different. Alix was now expected to give way to the new Queen Consort but Dagmar [Minnie], viewing things from her own experience, encouraged her sister to claim precedence.”

614

Alexandra had always been known for her graciousness and civility, so Grand Duchess Augusta believed she was being egged on by her imperious sister. “May that pernicious influence soon depart!” Augusta wrote to Queen Mary with her usual dramatic flair.

615

Mary’s quarrel with Queen Alexandra took a backseat to an even more personal family episode involving her brother Prince Frank of Teck. After retiring from the army and refusing to leave England in 1901, Frank had been living a carefree bachelor life in London paid for by credit. Following the debacle he caused by giving the Cambridge family jewels to his mistress, Mary did not speak to him for years. In the last few years, Frank showed glimpses of redemption, working assiduously to raise money for the Middlesex Hospital, a cause the queen found honorable and respectable, thus paving the way for a reconciliation between her and her prodigal brother. In the summer of 1910, Frank Teck underwent a minor nasal operation. He was prematurely released from hospital, after which Mary invited him to join her at Balmoral in the hopes of furthering their reconciliation. Within days, pleurisy set in, and Frank was dead.

Mary was heartbroken. She wrote to her husband, “Indeed you were more than feeling & kind to me about dear Frank, whose death is a great sorrow & blow to me, for we were so very intimate in the old days until alas the ‘rift’ came. I am so thankful I still had that nice week with him at Balmoral when he was quite like his old self & seemed to be so happy with us & our children.”

616

The funeral was held in Saint George’s Chapel at Windsor Castle. The queen, who rarely showed emotion in public, broke down sobbing. Writing to Aunt Augusta, she was relieved at her brother’s final resting place: “Dear Frank’s coffin lies with that of dear Mama. I think she would have wished this as she was especially devoted to him.”

617

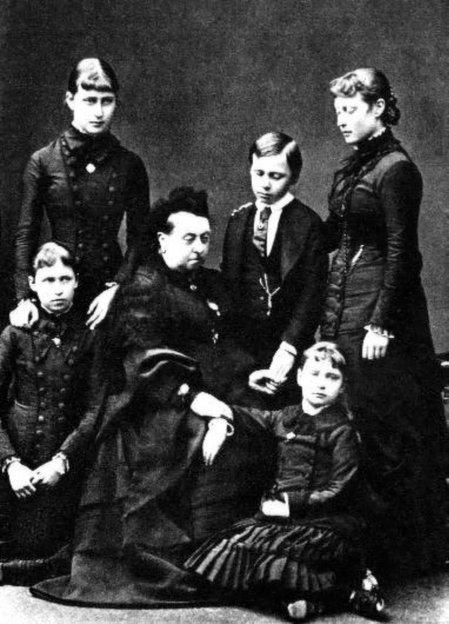

The Hessian children with Queen Victoria in mourning for their mother, 1879.

Left to right

: Ella, Victoria, Queen Victoria, Ernie, Irene, and Alix.

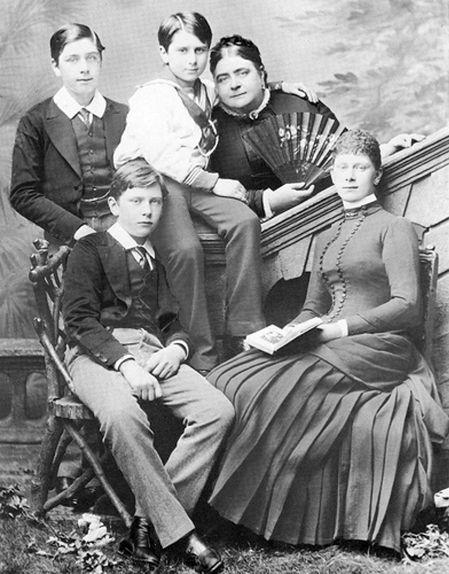

Princess May with her mother, the Duchess of Teck, and her brothers Dolly, Frank, and Alge, c. 1880.

Princess May of Teck, 1893.

Princess Alix and Tsarevitch Nicholas in a formal engagement photograph, 1894.

The Prussian royal family in 1896.

Standing, left to right:

Crown Prince Willy, Victoria Louise, Dona, and Adalbert.

Seated, left to right:

Augustus Wilhelm, Joachim, Wilhelm II (with Oscar seated in front), and Eitel-Frederick.