Impressions of Africa (French Literature Series) (2 page)

Read Impressions of Africa (French Literature Series) Online

Authors: Raymond Roussel

But the true originality of

Impressions of Africa

, as of most of Roussel’s major works, lies not in its attempts to out-Verne Verne, but in an invention that its author kept scrupulously hidden from sight. For in virtually every case, the episodes, conceits, and details from which Roussel fashions his characters and their actions were determined not by authorial whimsy but by a highly regulated process in which language itself is the sole motor and guide. The genesis of

Impressions of Africa

lies in a short story written some ten years before, “Among the Blacks,” in which the opening and closing sentences are virtually identical. Only one letter has changed in the passage from first to last, but on that small variant hangs the entire tale. As Roussel explained it:

I chose two almost identical words…For example,

billard

[billiard table] and

pillard

[plunderer]. To these I added similar words capable of two different meanings, thus obtaining two almost identical phrases…

1. Les lettres du blanc sur les bandes du vieux billard

…[The white letters on the cushions of the old billiard table]

2. Les lettres du blanc sur les bandes du vieux pillard…

[The white man’s letters on the hordes of the old plunderer]

In the first, “lettres” was taken in the sense of lettering, “blanc” in the sense of a cube of chalk, and “bandes” as in cushions.

In the second, “lettres” was taken in the sense of missives, “blanc” as in white man, and “bandes” as in hordes.

The two phrases found, it was a case of writing a story which could begin with the first and end with the latter.

In

Impressions of Africa

, the game expands to include not merely one altered sentence but a vast proliferation, in which moment after moment hinges on similarly complex puns. The examples are too numerous to detail here, but to lift the curtain on just a few:

The Luenn’chetuz, the ritual dance performed by Talou’s wives that results in copious belching, was generated by a dual interpretation of the phrase

théorie à renvois

: both a treatise with annotations (

renvois

)—in this case, Talou’s proclamation of his own sovereignty—and a procession (

théorie

) involving burps (

renvois

).

Revers à marguerite

(lapel with a daisy in the buttonhole) becomes

revers

(military defeat)

à Marguerite

(the French name for Gretchen in Goethe’s

Faust

), hence the rival king Yaour’s downfall while wearing Gretchen’s dress.

Toupie à coup de fouet

(a spinning top set in motion by a yank of the string) leads to the episode in which the old frump (

toupie

) Olga Chervonenkov is paralyzed by a muscle spasm (

coup de fouet

) while attempting a pirouette.

The talking horse Romulus, a true platinum standard (

étalon à platine

) among equines, is also an

étalon

(stallion)

à platine

(with a tongue, in slang).

Maison à espagnolettes

(house with window latches) yields the

maison

(as in dynasty) of the descendants of Suann, founded when the patriarch simultaneously married the two

Espagnolettes

, or young Spanish twins. (

Deux amours de Suann

? Given the frequent comparisons made between Roussel and Proust and the two men’s acquaintanceship, we can only wonder.)

None of this was apparent to the book’s few French readers, any more than it would be to their English counterparts today. Roussel the master magician kept his tricks well concealed, and only stepped out from behind the curtain to tip his sleight of hand in a posthumously published manual-cum-apologia pro vita sua titled

How I Wrote Certain of My Books

. With a mix of unvarnished literary altruism (“It seems to me that it is my duty to reveal this method, since I have the feeling that future writers may perhaps be able to exploit it fruitfully”), his lifelong hunger for recognition, and an almost infantile inability to withhold a really good secret, Roussel trots out example after example of his derivations like an unusually clingy merchant intent on hawking his wares.

At the same time, the process by which Roussel gave away his creative method mirrors the dual movement already encoded in

Impressions of Africa

: first the magic, then the revelation of its workings. At the novel’s halfway point, the author loops back to zero and starts his tale all over again, this time providing the missing back stories and justifications for the many curiosities we’ve just witnessed. Some editions even included an insert suggesting that “those who are not initiated into the art of Raymond Roussel” might wish to read the second half first. This would of course be to miss the point, for the first rule of magic is to keep your audience tantalized: dazzle before denouement.

The novelist Harry Mathews once remarked that Roussel’s language taught him how “writing could provide me with the means of so radically outwitting myself that I could bring my hidden experiences, my unadmitted self into view.” Hiding, concealment, non-admission are sewn into the fabric of

Impressions of Africa

—not just the behind-the-curtain mechanics of Roussel’s compositional generator, but likely something deeper as well: an incursion, despite himself, of the author’s personal reality into the “complete illusion of reality” he sought to achieve. It’s no secret today that Roussel’s proclivities ran to younger working-class males, but during his lifetime—and for decades afterward—it was cause for scandal and blackmail, and a source of mortification to his socially prominent family. We should therefore not be surprised at the role that secrecy and subterfuge play in the various plotlines of

Impressions of Africa

, nor, perhaps, in the fact that no adult sexual relationship in the book ends happily, and that they often have the dispassionate hue of a business transaction.

Indeed, virtually the only true love to be found here is that involving children—either the kind of substitute parent-child bond enjoyed by Velbar and Sirdah or, more often, between young quasi-siblings like Seil-kor and Nina or Meisdehl and Kalj. The painter and writer Trevor Winkfield notes that Roussel’s own love for his sister “was one of the most formative influences of his life,” and in that love seems to lie not only the kernel of the many idyllic brother-sister relationships in his work but an unhealed wound of nostalgia for the lost paradise of childhood itself. “Of my childhood I have preserved a delightful memory,” he confided in

How I Wrote

. “I can claim to have known at that time many years of perfect bliss.” So much so that he later said he’d felt no happiness since then, and that the memory of that former happiness was a source of torment. Just as Seil-kor after Nina’s untimely death rejects the places they had loved together, so, according to Leiris, Roussel refused to set foot in “certain towns which evoked particularly happy memories of his childhood…for fear of spoiling his memories.”

Instead, a spirit both childlike and childish infuses

Impressions of Africa

: marvelously, when it manifests as a constant openness to wonder, an ability to blur the lines of reality and fantasy without a grown-up’s sense of restraint; naïvely, in its conception of a benign world in which the heroes all aim to please (I am constantly amazed at how eagerly characters accede to the most outrageous requests “without having to be asked twice”), and in which the cardinal threat is boredom; selfishly, when it treats the actors in the grand gala as mere instruments of juvenile pleasure, taking it for granted that each performance will run smoothly and that nothing will break the spell; horrifyingly, when it indulges in the kind of pull-off-the-wings cruelty evidenced in the tortures and gruesome deaths of the four convicts, a dark blood-spatter on the immaculate waves of Roussel’s shifting, dazzling, treacherous, absorbing, blinding, engulfing African sands.

Every translation has its peculiar difficulties, and

Impressions of Africa

, with its special “method,” might seem more arduous than most. John Ashbery once noted that even though Roussel’s generative wordplay is buried well below the surface, its “presence imparts an undefinable, hypnotic quality to the text,” to which he felt no translation could do justice; whether I’ve managed to convey at least a measure of this quality I leave to the reader’s judgment. A further challenge lay in the compactness of the prose. Roussel prided himself on concision—“I forced myself to write each story with as few words as possible,” he told Leiris—and much of my effort has gone into fashioning similarly compressed English. In other respects, the pitfalls of rendering this book proved not unlike those offered by any literary text: how to capture the author’s signature style, in this case a peculiar mix of fluidity and flatness, invention and banality? how to preserve his turn-of-the-century phrasings and attitudes in a language that will speak to contemporary readers?

Then there are the author’s various idiosyncrasies and lapses, such as his frequent use of the word “certain” (a veritable tic), some continuity issues (captions that appear both above and below the image; prison bars that change from thick to narrow), and plot points that beg herculean suspensions of disbelief (did Louise and her brother really lug that sack of machine parts across half a continent? would the cannibals have let the captured Velbar keep his rifle? would his watercolor sketches still be so pristine after eighteen years in the jungle?—and how fortunate that he thought to bring along his art supplies while fleeing for his life!). Chalk it up to the quirks of genius.

Readers wishing further insights into Roussel’s life, work, and creative method are encouraged to explore Mark Ford’s illuminating study,

Raymond Roussel and the Republic of Dreams

(2000), from which I’ve borrowed a number of biographical pointers. In the domain of English-language commentary, John Ashbery’s essays “Re-establishing Raymond Roussel” (1962) and “In Darkest Language” (1967) remain the gold standard some fifty years after the fact, though they have since been seconded by essential writings from Harry Mathews and Trevor Winkfield. And of course, Roussel’s own

How I Wrote Certain of My Books

(trans. Winkfield) is a must. The present translation of

Impressions of Africa

is based on the

2005

Flammarion edition, edited and annotated by Tiphaine Samoyault, which also provided some source material for this introduction. To all of the above, my gratitude.

—MP, December 2010

A

T AROUND FOUR P.M.

that June 25th, everything seemed ready for the coronation of Talou VII, Emperor of Ponukele and King of Drelchkaff.

Though the sun had passed its zenith, the heat remained stifling in that region of equatorial Africa, and we all sweltered in the sultry atmosphere that no breeze came to relieve.

Before me stretched vast Trophy Square, located in the very heart of Ejur, the imposing capital formed by countless huts and lapped by the Atlantic Ocean, whose distant roar I could hear to my left.

The perfect quadrangle of the esplanade was bordered on each side by a row of venerable sycamores. From spears planted deep into the bark of each trunk dangled severed heads, banners, and ornaments of every kind, which Talou VII or his ancestors had amassed there upon returning from many a victorious campaign.

To my right, before the midpoint of the row of trees, a red stage stood like a giant puppet theater; its pediment bore the words “The Incomparables Club” in silver letters forming three lines, around which broad golden strokes radiated like sun’s rays.

On the visible stage, a table and chair appeared to be set for a lecturer. Several unframed portraits were pinned to the backdrop, underscored by an explanatory label that read “The Electors of Brandenburg.”

Closer to me, in line with the red theater, rose a large wooden pedestal on which Nair, a young Negro of barely twenty, was standing doubled over, absorbed in an engrossing task. To his right, two stakes, each planted at a corner of the pedestal, were joined at their uppermost tips by a long, supple thread that sagged under the weight of three objects hanging in a row, displayed like fairground prizes. The first item was none other than a bowler hat, the black crown of which bore the word “PINCHED” written in dirty white capitals; then came a dark gray suede glove turned palm outward and decorated with a “C” lightly traced in chalk; and last hung a light sheet of parchment covered in obscure hieroglyphs, its header boasting a rather crude sketch of five caricatures made plainly ridiculous by their poses and exaggerated features.

Imprisoned on his pedestal, Nair’s right foot was

collared

by a noose of thick rope firmly anchored to the solid platform; like a living statue, he performed a series of slow, regular movements while rapidly murmuring a string of words he’d committed to memory. In front of him, placed on a specially shaped stand, a fragile pyramid fashioned from three joined pieces of bark captured his full attention; the base, turned toward him and slightly raised, served as his weaving loom. Within reach, on an annex to the base, was a supply of fruit husks covered on the outside by a grayish vegetal substance much like the cocoon of a larva about to transform into a chrysalis. By pinching a fragment of these delicate envelopes with two fingers and slowly pulling back his hand, the youth created a flexible bond, reminiscent of the gossamer threads that stretch across the woods in springtime. These imperceptible strands helped him weave a subtle and complex embroidery, for his two hands worked with unparalleled agility, crossing, knotting, intermingling the fairylike ligatures into graceful patterns. The phrases he tonelessly recited served to regulate his perilous and precise maneuvers, for the smallest slip could have caused the whole structure irreparable damage. If not for the aid of a certain formula memorized word for word, Nair could never have reached his goal.

Lower down, to the right, other toppled pyramids at the edge of the pedestal—their tips facing away from the viewer—allowed one to appreciate the effect of these labors, once completed; each upright base was indicated by almost nonexistent tissue, more ephemeral than a spider’s web. In each, a red flower held by its stem irresistibly drew the viewer’s gaze through the imperceptible veil of the ethereal weave.

Not far from the Incomparables’ stage, to the actor’s right, two stakes set four to five feet apart supported a moving apparatus. A long pivot extended from the nearer of the two, around which a scroll of yellowed parchment was compressed into a thick roll; solidly nailed to the farther stake, a square board laid as a platform served as base for a vertical cylinder slowly made to revolve by clockwork.

The yellowish scroll, unspooling tautly over the entire length of the intervening gap, wrapped around the cylinder, which, turning on its axis, ceaselessly pulled it toward the other side, gradually depleting the pivot that was forced to spin along with it.

The parchment showed groups of savage warriors, rendered in broad strokes, parading by in highly varied poses. One cohort seemed to be in mad pursuit of the fleeing foe; another, crouching behind an embankment, awaited its moment to burst forth; here, two equally matched phalanxes engaged in fierce hand-to-hand combat; there, fresh troops surged bravely forward with grand gestures toward a distant melee. The continual procession offered endless surprises, owing to the infinite number of effects obtained.

Opposite, at the far end of the esplanade, rose a kind of altar preceded by several steps covered with a thick carpet. From a distance, a coat of white paint veined with bluish lines gave the whole the appearance of marble.

On the Communion table, represented by a long board placed halfway up the structure and covered with a cloth, one could see a rectangle of parchment dotted with hieroglyphics standing near a heavy cruet full of oil. Next to this, a large sheet of stiff luxurious paper bore the title, “Reigning House of Ponukele-Drelchkaff,” written scrupulously in Gothic letters. Beneath this heading, a round portrait, a kind of delicately colored miniature, depicted two young Spanish girls aged thirteen or fourteen, coiffed in the national mantilla—twin sisters, judging by their perfect resemblance. At first glance, the image seemed part and parcel of the document; but upon closer inspection, one noticed a wide band of transparent muslin, glued onto both the circumference of the painted disk and the surface of the durable vellum, that melded the two objects seamlessly, though they were in fact separate. To the left of the dual effigy, the name “SUANN” paraded in large capitals; beneath it, a genealogical chart comprising two distinct branches, descended from the two lovely Iberians who formed the apex, occupied the rest of the sheet. One of these lineages ended with the word “Extinction,” in letters almost as large as the title, clearly meant to catch the eye; by contrast, the other, stretching a bit lower than its neighbor, seemed to defy the future with the absence of any concluding sign.

Near the altar, to the right, a giant palm tree flourished, its admirable breadth attesting to its great age; a handwritten sign affixed to the trunk offered this commemorative phrase: “Restoration of the Emperor Talou IV to the throne of his forefathers.” Off to one side and sheltered by the palms, a stake planted in the ground supported a soft-boiled egg on the square ledge of its upper tip.

To the left, at an equal distance from the altar, a tall plant, but old and pitiful, made a sorry complement to the resplendent palm; this was a rubber tree, its sap run dry and in a state of near rot. A litter of branches placed in its shade supported the recumbent corpse of the Negro king Yaour IX, classically costumed as Gretchen from

Faust

in a pink woolen dress with alms purse and thick blonde wig, its long yellow plaits, thrown over his shoulders, reaching almost to his legs.

To my left, backed against the row of sycamores and facing the red theater, a stone-colored edifice looked like a miniature version of the Paris Stock Exchange.

Between this structure and the northwest corner of the esplanade stood a row of life-size statues.

The first showed a man mortally wounded by a spear plunged into his breast. Instinctively, his two hands clutched at the shaft; his body arched back on the verge of collapse as his legs buckled under the weight. The statue was black and at first appeared to be all of a piece; but gradually one’s eye discovered a multitude of furrows running in all directions, forming clusters of parallel striations. In reality, the work was composed entirely of numerous whalebone corset stays cut and molded as the contours dictated. Flathead nails, their tips evidently bent beneath the surface, jointed these supple strips together so artfully that not the slightest gap remained between them. The face, its nose, lips, eyebrows, and eye sockets faithfully reproduced by minutely arranged little sections, bore a finely rendered expression of pain and anguish. The shaft of the weapon buried in the dying man’s heart suggested some great difficulty overcome, thanks to the elegant handle that showed two or three stays cut into small rings. The muscular body, clenched arms, and nervous, crooked legs all seemed to tremble or suffer, due to the striking, flawless curves imposed on the invariable dark-colored strips.

The statue’s feet rested on a simple vehicle, its low platform and four wheels composed of other black, ingeniously combined whalebone stays. Two narrow rails, made from some raw, reddish, gelatinous substance, which was none other than calves’ lungs, ran along a dark wooden surface and, by their form if not their color, created the precise illusion of a section of railroad track. It was onto these tracks that the four immobile wheels fit, without crushing them.

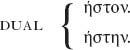

The surface supporting the tracks formed the top of a jet black wooden plinth, the front of which bore a white inscription with these words: “The Death of the Helot Saridakis.” Below it, also in milky letters, one saw this phrase, half-Greek and half-French, accompanied by a slim bracket:

Next to the helot, the bust of a thinker with knit brow wore an expression of intense and fruitful meditation. On the stand one could read the name:

IMMANUEL KANT

After this came a group of sculptures depicting a thrilling scene. A cavalry officer with the face of a thug seemed to be interrogating a nun flattened against the door of her convent. Behind them, in bas-relief, other men-at-arms mounted on fierce steeds awaited orders from their chief. On the base, in chiseled letters, the title

The Nun Perpetua’s Lie

was followed by the question, “Is this where the fugitives are hiding?”

Farther on, a curious recreation, accompanied by the explanatory caption, “The Regent Bowing before Louis XV,” showed Philippe d’Orléans paying his respects to the ten-year-old child king, who maintained a pose full of natural, unconscious majesty.

Unlike the helot, the bust and these two complex groupings were made of what looked like terracotta.

Calm and vigilant, Norbert Montalescot strolled among his works, watching especially over the helot, whose fragility made a careless jostle from some passerby a matter of special concern.

Past the final statue stood a small cabin with no doors, its four walls, of equal width, made of heavy black cloth that in all likeli-hood left the interior completely dark. The gently sloped roof was strangely composed of book pages, yellowed by time and trimmed into tiles; the text, fairly large and exclusively in English, was faded or completely erased, but the visible headers of certain pages still bore the clearly printed title

The Fair Maid of Perth

. The middle of the roof contained a hermetically sealed skylight, made not of glass but of similar pages, also discolored by wear and age. This delicate tiling no doubt filtered a diffuse, yellowish light, soft and restful.

A kind of chord, suggesting the timbre of brass instruments but much fainter, escaped at regular intervals from inside the cabin, like musical breaths.

Just opposite Nair, a tombstone, in perfect alignment with the Stock Exchange, supported various elements of a Zouave’s uniform. A rifle and cartridge pouches lay alongside these military effects, which to all appearances served as a pious memento of the departed.

Rising vertically behind the funerary slab, a panel draped in black fabric offered a series of twelve watercolors, arranged in threes over four even, symmetrically stacked rows. Given the similarity of the characters depicted, the suite of paintings seemed to relate some continuous dramatic narrative. Above each image one could read, like a title, several words traced with a brush.

On the first sheet, a noncommissioned officer and a flamboyantly attired blonde were camped in the back of a luxuriously appointed victoria; the words “Flora and Lieutenant Lécurou” summarily designated the couple.

Then came “The Performance of

Daedalus

,” represented by a wide stage on which a figure in a Greek toga appeared to be singing lustily; in the front row of a box, one again found the lieutenant sitting beside Flora, who was training her opera glasses on the performer.

In “The Consultation,” an old crone wearing an ample sleeveless cloak drew Flora’s attention to a celestial planisphere pinned to the wall, and leveled an authoritative finger at the constellation Cancer.