In Fond Remembrance of Me (3 page)

Read In Fond Remembrance of Me Online

Authors: Howard Norman

Fate constructs memory in unforeseen ways. Given a certain compression of circumstances, a give-and-take honesty, a modicum of good cheer and sociability, and if you are able to embrace each other's take on life, you can learn quite a lot about a person in a short period of time. Late one morning, just a week after I had arrived in Churchill and set up in the motel, I stopped by Helen's room. I had not seen her that morning at breakfast at the Churchill Hotel, already an unusual absence since we had begun a routine of meeting for breakfast from day one. I knocked on her door and heard a weak “Come in.” I opened the door and saw Helen curled up on the bed, clutching her stomach. She looked pale and there was a white film along her lips. She was fully dressed, including her green parka with plaid lining and what she told me was her favorite item of clothing, black buckle-up galoshes she had bought in Halifax. The shades were drawn; the sedatives Helen took sometimes made her eyes excruciatingly sensitive to light. “You okay?” I asked.

“I have stomach cancer,” she said. She said it matter-of-factly. “So, there, now you know.” I might have expected something else here. Some further explication. Even some judgment of my blank expression. But I soon realized that

unembroidered self-assessment was an expertise of Helen's. She closed her eyes a moment, took a drink of water. Rub my feet, will you?” she then said.”Sit and listen to the CBC for as long as you like, okay?” In discussing novels, Helen appreciated when a plot unfolded or a truth was revealed by indirection. This was paradoxical. Because in her own life, in conversations, she did not suffer indirectness.”Come to think of it, an hour listening to the radio will do.”

unembroidered self-assessment was an expertise of Helen's. She closed her eyes a moment, took a drink of water. Rub my feet, will you?” she then said.”Sit and listen to the CBC for as long as you like, okay?” In discussing novels, Helen appreciated when a plot unfolded or a truth was revealed by indirection. This was paradoxical. Because in her own life, in conversations, she did not suffer indirectness.”Come to think of it, an hour listening to the radio will do.”

I do not, here, want the fact of her cancer to import sentimentality into these recollections. Helen, I am convinced, would have despised that, chastised me for doing so even unwittingly. She would, I believe, have considered it a failure of character. In a letter she wrote, “I hate that my illness put such boundaries on elation.” That sentenceâ! Given what was no doubt her mind-boggling pain and frustration, that sentence so characteristically bespoke Helen's writerly self. Elegant in restraint.

Upon her own arrival in Churchill, Helen had immediately set up a routine. She worked with Mark Nuqac all morning as her stamina allowed, beginning directly after breakfast. That is, if Mark was availableâhe was unreliable in this regardâtaping, transcribing, discussing the Noah stories. Now and then I sat with Helen in Mark's cramped kitchen, with children and adults coming and going, this cousin or that, tea or coffee being prepared, potatoes being fried, the radio on, and on certain occasions such a pervasive air of distraction that it was difficult to imagine getting any translation work done, though Helen was stringent in her attempt to keep things on track. (Domestic chatter, radio music, and, in one instance, a child jumping on a bed with

squeaky springs is background noise on several tapes of my own working sessions with Mark.) But more often than not, Helen visited Mark on her own, and early on Mark informed me he preferred it that way. My own work with Mark was altogether a less predictable arrangement. Mark really kept me on my toes with scheduling, seeing that he didn't much want to work with me at all, or did so grudgingly. We might work all afternoon and late into the night, and subsequently not work for three or four days on end. “I know where to find you,” he was fond of saying. In Mark and his wife Mary's house food was always offered. (Mark liked snacking on chunks of raw carrot or boxed breaksticks with peanut butter. Also, he enjoyed black coffee with half a dozen teaspoons of sugar.) But Helen's appetiteâher ability, that is, to keep down foodâwas meager. Her personal pharmacy was always close at hand, eight or nine vials of pills were either on her night table or stuffed into her parka pockets or backpack. And as for generally bearing up, over tea one morning she said, “Despite my medical circumstances, most days I don't feel life is rushing by, oddly enough.”

squeaky springs is background noise on several tapes of my own working sessions with Mark.) But more often than not, Helen visited Mark on her own, and early on Mark informed me he preferred it that way. My own work with Mark was altogether a less predictable arrangement. Mark really kept me on my toes with scheduling, seeing that he didn't much want to work with me at all, or did so grudgingly. We might work all afternoon and late into the night, and subsequently not work for three or four days on end. “I know where to find you,” he was fond of saying. In Mark and his wife Mary's house food was always offered. (Mark liked snacking on chunks of raw carrot or boxed breaksticks with peanut butter. Also, he enjoyed black coffee with half a dozen teaspoons of sugar.) But Helen's appetiteâher ability, that is, to keep down foodâwas meager. Her personal pharmacy was always close at hand, eight or nine vials of pills were either on her night table or stuffed into her parka pockets or backpack. And as for generally bearing up, over tea one morning she said, “Despite my medical circumstances, most days I don't feel life is rushing by, oddly enough.”

Indelibly, every mental snapshot I retain of Churchill contains a raven or a group of ravens; the same with my dreams of Churchill. Ravens simply crowd into the picture. The proper terminology, I believe, is “a parliament of ravens.” (It is “a murder of crows.”) Ravens on the taiga, on the tundra, on the ground, in the black spruce of the bogs. Ravens along the railroad tracks. Ravens at the grain silos, out at the granary ponds, along the river. Then there is a kind of slapstick comedy one sees: raven dive-bombing polar bears foraging at the Churchill garbage dump, or nipping at a bear's genitals as it lolls on its back along the rocky beach of Hudson Bay.

There were two ravens as a greeting party when I stepped off the airplane on my first day at Churchill. Helen had arrived on August 22; I had arrived on August 27. Helen had taken the “Muskeg Express” train up from Winnipeg. My pilot's name was Driscoll Petchey (I used this name for a pilot in a novel,

The Haunting of L

., set partly in Churchill), a real chatterbox. Setting my one suitcase on the ground, Petchey said, “Good luck every minute from now on,” then walked ahead of me to the airstrip's small office.

The Haunting of L

., set partly in Churchill), a real chatterbox. Setting my one suitcase on the ground, Petchey said, “Good luck every minute from now on,” then walked ahead of me to the airstrip's small office.

Mark Nuqac's nephew Thomas drove me to the Beluga Motel. Not more than ten minutes after unpacking, there

was a knock on the door. I opened it and there stood Helen.

was a knock on the door. I opened it and there stood Helen.

“I have a very Japanese face, as you can see,” she said, “but I'm English on my mother's side.”

“What's your name? Why did you knock on my door?”

Helen was dressed in her green parka, a black turtleneck sweater underneath, blue jeans, those galoshes buckled to the top. Her black hair was tied up in back; she also had a kind of topknot, just on the very top of her head, which made me almost laugh. Stray hairs spilled out from the knot like a fountain.

“I'm Helen Tanizaki,” she said, taking my hand in hers and shaking it. She let go of my hand and said, “Come on, I'll take you over to see Mark. He's in a very bad mood. He can't wait to meet you.”

“Just a minute. How did you even know I was assigned to work with him? With Mr. Nuqac.”

“Because I'm working with him, too. He mentioned you. Then you got here.”

“You're working with himâin what sense?”

“Same as you, as it turns out.”

“Same as me how?”

“Well, it's my understandingâam I mistaken?âthat you're going to try and translate some of Mark's stories. And you've been hired by some museum or other. And that's why you're here.”

“Correct.”

“Soâyou are translating into English, right?”

“Yes.”

“Me, I'm translating the same stories into Japanese. For a journal, and later possibly for a book.”

“Nobody told me this would be the situation.”

“Me either, Howard Norman.”

“Mr. Nuqac had to agree to it, though.”

“Of course. It was his idea.”

“Why would he do that?”

“For one thing, he makes twice the money.”

She shook her head side to side, as though I was the most naïve person on earth. “Okay, ready?”

“Yes.”

“Put on your coat, then.”

When we arrived at the small shack-like house Mark had borrowed for his stay in Churchill (Mark and his wife, Mary, had arrived from Eskimo Point via Winnipeg, where Mary had had a minor operation in the hospital), Helen said, “This part of town is called âthe Flats.'” The Flats was where some of the original parts of Churchill still remained; one brochure, or reference guide, said, “If you want to see how the Indians used to live in Churchill [referring mainly to the Cree], go have a look,” euphemistic, I suppose, for declaring this area a kind of shantytown. My knock on the door was answered by Mary, who announced, without being asked, that Driscoll Petchey was, as we spoke, flying Mark the short distance to Padlei “to visit some cousins.”

I killed time for two days, sizing up the town of Churchill, eating breakfast and dinner with Helen at the Churchill Hotel, going for walks carrying a rifle borrowed from Thomas, “in case of bears.” When Helen told me that Mark had returned, I walked over to finally meet him. We did not shake hands; we just nodded hello. Mary just stood there observing this interaction without the slightest look of surprise.

“Okay, I've met you,” Mark said. “The museum already sent some money. Ask Helen, here, when to see me. We can start working pretty soon, eh?” It was clear I was then to leave, which I did. I ate dinner with Helen at 7 p.m. at the Churchill Hotel, arctic char, potatoes, thawed vegetables, coffee. Just like every other night so far.

“Okay, I've met you,” Mark said. “The museum already sent some money. Ask Helen, here, when to see me. We can start working pretty soon, eh?” It was clear I was then to leave, which I did. I ate dinner with Helen at 7 p.m. at the Churchill Hotel, arctic char, potatoes, thawed vegetables, coffee. Just like every other night so far.

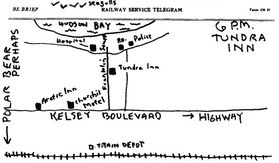

Here is a drawing of Churchill Helen made for me:

CANADIAN NATIONAL RAILWAYS

As I have mentioned, Mark referred to his stories as “my Noah stories.” Generally, they each had these four things in common:

1.

Noah's Ark drifts into Hudson Bay as winter is fast approaching.

Noah's Ark drifts into Hudson Bay as winter is fast approaching.

2.

Inuit villagers offer a bargain, or strongly suggest that Noah give up some of his unusual animalsâand/or planks of wood from the arkâin exchange for their keeping Noah's family alive through the winter.

Inuit villagers offer a bargain, or strongly suggest that Noah give up some of his unusual animalsâand/or planks of wood from the arkâin exchange for their keeping Noah's family alive through the winter.

3.

Noah refuses; said refusal engenders all manner of incident and repercussion.

Noah refuses; said refusal engenders all manner of incident and repercussion.

4.

After the spring ice-break-up, the ark sinks. Noah (and whichever members of his family who have survived) is sent packing southward on foot.

After the spring ice-break-up, the ark sinks. Noah (and whichever members of his family who have survived) is sent packing southward on foot.

Ancient Inuit life so vividly animated in the Noah stories was, to say the least, hand-to-mouth. Fish had to be caught on a daily basis, seals or bears had to be killed as often as possible simply for people to exist. Not only can one read nineteenth-century ethnographic accounts or explorers' journals to get a sense of all this (keep in mind that Mark said his stories were “from Bible times,” though we never discussed what he meant exactly), but of course traditional Inuit folktales are full of hardships. Hunting journeys were long, arduous, fraught with anxietiesâand no doubt replete with joy, laughter, altruistic purpose, and the highest level of engagement with the physical and spiritual worldâand, as often as not, unsuccessful. Starvation was not uncommon.

So: along comes a huge wooden boat full of elephants, giraffes, zebras, all sorts of curious, substantial-looking beasts. In a world of either feast or famine, imagine the sight to Inuit people as they looked up from their kayaks or sleds (as they do in Mark's stories) of such potentially grand meals in the making.

Ethnologists use the phrase “first contact stories” as a category of old-time narrative which depicts the exact moment in history when indigenous peoples first laid eyes onâspoke with, traded with, fought with, fled fromâEuropeans. The Noah stories, I think, basically fit that description. I asked

Mark Nuqac about this. I said, “Were there any white people up here before Noah showed up?”

Mark Nuqac about this. I said, “Were there any white people up here before Noah showed up?”

Mark said, “No.”

Â

Â

Â

THE ARK IS TOO LOUD

Â

One day at the beginning of winter, a big wooden boat was caught in the ice. The same day, a feared shaman showed up. This shaman walked directly into the village. “Did you invite that boat here?” he said.

“No,” the villagers said. “We don't know why it's here.”

“I like to sleep on the ice,” the shaman said. “I like to sleep near seal breathing-holes.”

“We know that.”

“There's loud noisesâanimal barks, grunts, snores, shouts, yelpsâcoming from that boat. The boat is keeping me awake. Seals have the same complaintâthey like to sleep on the ice, too.”

In a short while winter arrived. The sea was covered with ice.

“You go out and stop the noise,” the shaman said. “Go out there and stop it. Or else I'll cram your villageâeverybody, everythingâdown a seal breathing-hole. I can't sleep.”

With this, some village men walked out over the ice to the boat. They shouted up, “Whose boat is this?”

“It's mineâmy name is Noah,” a man shouted down. “This is my wifeâthis is my sonâthis is my daughter.” His family stood there now.

“What's this boat called in your language?”

“An ark,” this Noah said.

“Why does it make so much noise?”

“It's full of animals,” Noah said.

“We can smell them all the way into our villageâare they tasty, what do they taste like, are they good to eat, will you share some with us?” a man said.

“No-no-no-no-no-no-no-no-no!” said Noah.

“What?”

“No!” said Noah.

“Why are you here?”

“I got lost.”

“Can you sleep with all that noise nearby?”

“No,” said Noah. “No,” said Noah's wife. “No,” said Noah's daughter. “No,” said Noah's son.

“Look out there on the ice,” a villager said. “What do you see?”

“A man asleep on the ice. Now he's woken up,” Noah said.

“Well, that man has big powersâand he's angry at your ark. He can't sleep. The ark is too loud. That manâif the ark stays loudâwill cram our village through a seal breathing-hole. If the ark stays loud, that man will probably turn all of your animals inside out.”

“Nobody can do such things,” Noah said.

“You are wrong,” a village man said.

“Here's what you should do,” another man said to Noah. “Give us a few animals to eat. Give us a few planks of wood to make a fire with. Then give all the rest of the animals to that manâthe shamanâand he'll cram them all through a seal breathing-hole. Then he'll be able to sleep. Then he won't turn the animals inside out, and he won't kill you, either.”

Noah said, “No.”

The villagers walked over to the shaman. “I can't sleep,” he said.

The villagers sat next to him. When they sat down, the ark began making a lot of loud noises! “The man named Noah, there on the boat, won't make the noise stop,” a village man said.

With this, the shaman flew to the top of the ark. “Your boat is too loud,” he said. He took up Noah's wife and flew her around. They traveled. They came back. “Give up those animals,” the shaman said.

“No!” said Noah.

The shaman took Noah's daughter and slipped with her through a seal's ice breathing-hole. They were gone for a few days. When they came back, Noah's daughter said, “Father, I don't want to do that again. Give up the animals.”

“No,” Noah said.

The shaman climbed onto the ark. He turned Noah's son inside outâsome seagulls flew and plucked up the guts and insides, and flew off. Then the shaman turned each of the animals below deck on the ark inside out. He put them on deckâravens and gulls flocked inâall the guts and insides were plucked up.

The shaman went out and lay down next to a seal breathing-hole. He fell asleep.

When the ice-break-up arrived, the shaman pried off a lot of planks. He gave a few to the village. He flew off carrying many ark planks. The ark sank away.

Noah and his family were taken into the village. They lived there much of the summer, Noah, Noah's wife, Noah's daughter.

One day, they wrapped themselves in the dried skins of some animals the shaman had turned inside out, and set out on foot in the southerly direction. There wasn't an ark in Hudson Bay again.

Other books

The Bridal Path: Danielle by Sherryl Woods

The Memoirs of a Survivor by Doris Lessing

Brighter Than the Sun by Darynda Jones

Deadlock by Mark Walden

Pleasure Point-nook by Eden Bradley

The Good Soldier by L. T. Ryan

Satan's Story by Chris Matheson

The Adventures of Phineas Frakture by Joseph Gatch

One Grave at a Time by Frost, Jeaniene

Take Me Home: Home is Where the Heat Is, Book 3 by Candi Wall