In Search of the Niinja (6 page)

Read In Search of the Niinja Online

Authors: Antony Cummins

To compound the problem, ninjutsu manuals use both of the above versions (and more) in the same section of text and there appears to be no reason why they switch between the two. The

Shinobi Hiden

uses both versions, as does the

Bansenshukai

, whereas the

Taiheiki

war chronicle and the

Gunpo Jiyoshu

military arts manual only use one version each. The

Gokuhi

manual uses only phonetic markers or

or . However, the

. However, the

Koka Shinobi Den Mirakai

manual dictated by the samurai

-

ninja

named

Kimura Onosuke states that the tacticians of his time do not understand the difference between these two forms of ninja, so he differentiates between the two types of ninja agent. Cross-referencing with other documentation, it can be concluded that in the minds of some chroniclers the ninja can be separated into those who spy in a classic sense, that is, those included in Sun Tsu’s five spies, and those ninja who steal in by stealth alone.

In summary, the term shinobi was well established from the time of the

Taiheiki

in the late fourteenth century. It continued to be used through to the Sengoku period. The word shinobi as a title is by no means a modern invention, making the ninja at least 700 years old, if not older.

To understand the difference between the term

Nusubito

(thief) and shinobi we need to know what kind of stealing they were doing. First it must be understood that the term

Nusubito

is a generic word for thief. Which means that simply finding the word

Nusubito

in a document does not confirm a shinobi reference, however, further markers in the text will help prove if the form of stealing was similar to that of a ninja

or not. The following two examples are taken from the military writings of Todo Takatora, a distinguished Sengoku period general who was active at the height of the Japanese civil wars.

If you have been robbed by a Nusubito, do not investigate the issue, it may turn out that you will be ridiculed in the end for your carelessness [for allowing the theft to take place]. Furthermore, even if you identify who the thief is, do not pursue the acquisition because it may turn out that he is a part of a retainer’s group, therefore you should reduce any form of punishment [if the case arises]. Otherwise you will have to submit notice that these hired retainers are of the same ilk [as the associated thief]; and further, you should consider the stolen object to be lost and not pursue the criminal and also, you should restrain your greed.

The words are for the samurai class and imply that the thief in question is either of lower samurai status or an aide connected to a samurai retainer. By the context of this description we know that Todo is talking here of infiltration into a house. The idea that the victim does not know who the culprit is and the fact that he did not simply cut him down in the street implies this was not face-to-face banditry or street robbery. Also, the loss of an object precious to you would suggest it was contained in your living area. So the

Nusubito

here was using the arts of infiltration to gain entrance into a house or restricted area with the intent of stealing for profit.

Todo continues his message about the art of the Nusubito: ‘Whilst you are young, learn all kinds of arts, as it is easy to throw them away at a later point. You should even learn the art of the Nusubito thief, as it will teach you the ways of defence against thievery itself.’

So the samurai class is exhorted to learn the art of thievery, something that seems to have been more common than we thought. This perfectly matches the teachings of the

Tenshin Katori Shinto Ryu

sword school of Japan, a 600-year-old sword school that teach the arts of the ninja to their students to help them defend against ninja theft.

The following two quotations from the

Jinkaishu

statute imposed by the Date clan, probably around the year 1536, speak about the concept of

Nusubito

and indirectly the issue of arson, and show the way in which people thought about

Nusubito

thieves:

Setting ablaze to a person’s property is a serious crime which is equivalent to that of Nusubito thievery.

Those peasants who do not pay tax or the required dues to a Jito estate steward and who flee to another province should be charged with a seriousness equivalent to that of a

Nusubito

thief. Therefore, those who give them quarter should give notice and hand them over. If they do not and continue to give them shelter, then they too will be as guilty as the fugitives themselves.

Remembering that the skill of the shinobi is akin to that of the

Nusubito

and in truth are only separated by motive, then we can see where a negative opinion of shinobi may have come from.

Lord Kujo Masatomo (1445–1516) was a court noble who left behind the document

Masatomo Ko Tabi Hikitsuke

or

Record of Masamoto

’

s Travels

, in which we see more laws and punishments concerning the

Nusubito

thief.

The sixteenth day of the second month of 1504

It was raining when the headmen of Oki and Funabuchi Village reported to the Lord and they said:

‘Because of the drought of last year, a lot of peasants have died. So we have gathered bracken and barely managed to survive. However, someone is stealing our food from us and as we would die if our stocks run out, we decided to keep guard over it. Recently, some came to steal from the storehouse and we gave chase and found them running into the house of a woman fortune teller of Takimiya shrine. When we entered we found they were her two sons and because they were the

Nusubito

, we killed all three of them, the mother and her two sons. We have come to report this with respect.’

Lord Masatomo’s wrote about this case:

It is quite harsh that they killed them all, even their mother and that there are no witnesses left. However, accounts of

Nusubito

activity have been frequently rumoured of late and the punishment for lower village people should be decided among themselves, so this cannot be helped as they [the thieves] must take the consequences of their own deeds as

Nusubito. Namuamidabutsu

[a Buddhist prayer].

So as early as the 1200s, samurai and military personnel were already proficient in clandestine operations and they used their knowledge of the art of creeping in to profit by theft. In times of war, these skills were being used by generals for clandestine infiltration into enemy positions. Also, at some point, the shinobi become a specialisation within the military class. Two versions of the word ‘shinobi’ are used to describe a person with a selection of specialised skills later known as

shinobi no jutsu

. In addition, theft was common and considered a skill among all classes including the samurai, who were active thieves throughout much of samurai history.

In 1487, the ninth

Ashikaga

Shogun, Yoshihisa, took up position in a temple in Magari, where he was in conflict with Rokkaku Takayori, who was the governor of Omi province. One night during the long encampment, 1600 from the Rokkaku camp including men of Koka and Iga conducted a surprise night raid on the Shogun’s quarters. It is said they succeeded in getting in the Shogun’s bedroom and injuring the Shogun himself, an injury which caused his death the following year. For their abilities and conduct, 21 families of Koka were given a letter of appreciation for their achievements and the

Omi Onkoroku

document (1684–1687)

17

states the following:

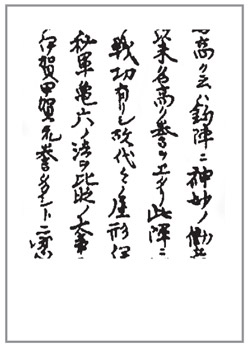

The

Oumi Onkoroku

.

The

shinobi-shu

of Iga and Koka are renowned because they accomplished an amazing feat at the battle of Magari-no-jin, earning the respect of the massive army gathered there. Since then they have achieved great fame.

The document then continues to describe the tactics of the warriors as

Kiroku no Ho

or the ‘six way method of the turtle’, which is a reference to how a turtle retreats into its shell.

Like a turtle, which pulls in its four legs, head and tail, the people from Iga and koka conducted surprise attacks on the Shogunate’s massive army and quickly retreated into the mountains. The army was lured in after them, where [the Iga and Koka people] were waiting for them and thus they attacked by dropping logs or stones from above, trapping them in pits, etc.

During the Sengoku period, records of the ninja, such as the

Gunpo Jiyoshu

18

and others

19

make their mark, however, as the Sengoku period was a time of war, records are not easy to obtain. Accounts of the Tokugawa family hiring shinobi for campaigns exist, the term

Iga

and

Koka no mono

or ‘Men of Iga and Koka’ become bywords for the ninja and talk of

Iga-shu

and

Koka shu

becomes more common, possibly more so than the word ‘shinobi.’

Ninja manuals from the Sengoku period are rare. The

Ogiden

document claims and is believed to be from the late 1500s and the

Shinobi Hiden

manual by Hattori Hanzo I claims to be from 1560. Both use the word shinobi as we know it. One possible reason for the lack of manuals is the destruction of Iga in 1581, as the warlord Nobunaga burnt his way through the land and brought the independent states of Iga under control, leaving nothing but ashes behind. Secondly, the need for manuals in the Sengoku period was significantly less then in the period of peace, as skills were used in everyday life and a level of practical ninjutsu was needed to be effective in war.

The Sengoku period military manual, the

Gokuhi Gunpo Hidensho

20

uses the word

shinobi

:

Understanding if the Enemy are Experiencing Famine:

To identify the status of the enemy, you should send a shinobi to pretend to be a woodcutter or mower in the enemy’s territory. He should have the lower ranking people of that area drink

to pretend to be a woodcutter or mower in the enemy’s territory. He should have the lower ranking people of that area drink

21

[alcohol] and then he should listen to their conversation for clues.