In the Clear

In the Clear

In the Clear

A

NNE

L

AUREL

C

ARTER

O

RCA

B

OOK

P

UBLISHERS

Copyright © 2001 Anne Laurel Carter

No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior written permission of the publisher or, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, a licence from CANCOPY (Canadian Copyright Licencing Agency), 6 Adelaide Street East, Suite 900, Toronto, Ontario, M5C 1H6.

Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data

Carter, Anne, 1953â

In the clear

ISBN 1-55143-192-0

I. Title.

PS8555.A7727I65 2001 jC813'.54 C2001-910131-7

PZ7.C2427In 2001

First published in the United States, 2001

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2001086678

Orca Book Publishers gratefully acknowledges the support for our publishing programs provided by the following agencies: The Government of Canada through the Book Publishing Industry Development Program (BPIDP), The Canada Council for the Arts, and the British Columbia Arts Council.

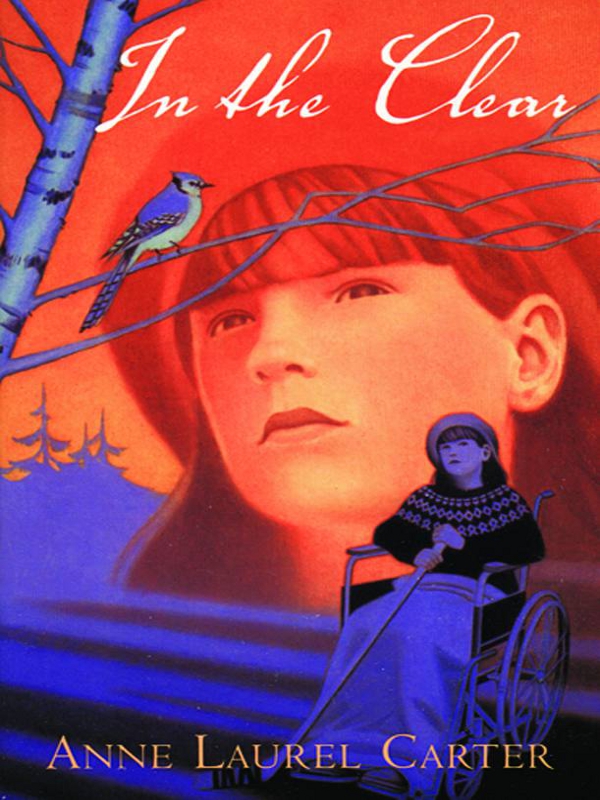

Cover illustration by Ron Lightburn

Cover design by Christine Toller

Printed and bound in Canada

IN CANADA

:

Orca Book Publishers

1030 North Park Street

Victoria, BC Canada

V8T 1C6

IN THE UNITED STATES

:

Orca Book Publishers

PO Box 468

Custer, WA USA

98240-0468

03 02 01 ⢠5 4 3

The author would like to acknowledge the support of the Canada Council and the Ontario Arts Council.

For Janet Abernathy

and

Mary Richardson,

who gave me their stories.

Contents

3. DREAMING WITH TANTE MARIE, 1959

4. IN THE HOSPITAL FOR SICK CHILDREN, 1954

5. CHRISTMAS WITH TANTE MARIE, 1959

6. THE HOUSE OF HORRORS, JANUARY 1955

8. HENRY'S VISIT TO THE HOUSE OF HORRORS, 1955

9. FUNERALS ARE FOR FAMILIES, 1960

11. SECOND CHANCE SPRING, 1960

14. THE NEW BRACE AND SHOE, 1955

16. FACE-OFF: THE HOUSE OF HORRORS, 1955

“It's Hockey Night in Canada,” I holler. My voice swells in a perfect imitation of my favorite TV announcer, Foster Hewitt, on a Saturday night.

“In goal for the Montréal Canadiens ⦠Jacques Plante.”

“Quiet, Pauline!” my mother scolds from the kitchen. “I'm on the phone. Long distance to Grand-mère in Montréal.”

“In goal for the Maple Leafs ⦔ I raise my voice a notch louder. Grand-mère is a Canadiens fan. “⦠Johnny Bower!” Time for a whistle, long and shrill. Grand-mère knows that the only thing I enjoy more than hockey is making my mother good and mad.

High heels click across the kitchen floor.

I wait. I push my thin, shrunken left leg to one side of my throne, the cushioned window seat overlooking our backyard. I used to wait for my mother's home-school lessons at the kitchen window at the front of the house. I used to watch for my old friend â my old best friend â Henry Patterson, walking to school with Stuart O'Connor and Billy Talon. Until one day a new girl on our street stopped and pointed at me. “Look!” she yelled. “Is that Polio-Pauline? I heard she caught it from the Don Mills pool.” Four girls turned and stared at me. I stuck out my tongue and they ran, afraid they might catch it.

On my window seat, I position the little metal men on my dad's old table-hockey game for a face-off. My dad and I are big Leafs fans. We're hoping we'll win the Stanley Cup this year. When I play hockey on the window seat at the back of my house, the blue paint-chipped Maple Leafs never lose.

“Pauline!” My mother stares from me to the hockey game to the stack of books she left within reach this morning.

I never reach for the books she leaves me.

Her voice accuses me of betrayal. “You haven't read a thing all morning!” She grabs my table-hockey game and turns away. The accordion pleats of her gray flannel skirt flick the air. Before I can stop her, she's locked my game in a cabinet on the other side of the room.

“No fair,” I yell. My metal leg brace is off and my crutches are on the floor.

“You refuse to read the books I give you! You do it to annoy me.”

Now I turn away. Outside the window, I see my dad skating figure eights around our new backyard rink. He flies by, waving to me. He's so pleased with himself for finally building a rink this winter. My mother wasn't keen on the idea. Every year she gave more reasons. Like, what if there's a thaw and water floods the basement? What if a puck breaks a window? Who's Dad going to play with? What if kids sneak over the fence in the middle of the night and get hurt? My mother can be such a dream squelcher. But this year â maybe it's the Stanley Cup fever â Dad ignored her and built it anyway. Our wide backyard is meant for a rink, he says. The wooden fence on both sides makes natural endboards when he shoots pucks. He bought nets and froze them into the ice. Years ago, he played hockey at high school and university, and now when he goes out to skate, he's dreaming he plays for the Leafs.

If only I could fly out there with him, so powerful and free.

Suddenly I see Henry, my once-upon-a-time best friend. He's jumping over the fence, the endboards, wearing his skates. He begins to race around the rink with my dad. Henry plays on a Don Mills hockey team â I've watched him leave for a hundred games with that big, black bag of his. He's fast, almost as fast as my dad.

What a show-off! Wouldn't you know he'd be the first kid out with my dad on my new rink?

I thump the window. Henry looks up. I glare, stick out my thumb and jerk it sideways, the unmistakable sign for go away, my gesture to Henry from the time I was in the hospital and did not speak for months.

“This could be Grand-mère's last Christmas,” my mother says, her voice soft with apology and regret. She never stays mad at me for long.

Henry's shoulders droop. My dad says something before he leaves. Dad likes Henry. If the Leafs make it to the playoffs, he'll ask Mr. Patterson and Henry to watch a Saturday night game with us. I'll hate it. Dad thinks I'm alone too much, but it's way better, just Dad and me. If Henry comes, I'll hide my leg under a blanket and I won't cheer or say a word. I still don't speak when Henry's around.

I turn to glare at my mother. Her hands fuss nervously with the perfect bun at the back of her head. “She wants to come visit us, but she can't travel alone.”

“Can't someone bring her?”

“No. My sisters are busy with their families. All your cousins want to stay home for Christmas.”

We usually celebrate Christmas at Tante Giselle's or Tante Mireille's in Montréal. My parents think it's good for me to see my cousins. But last year we drove through a blizzard and my mother swore, “No more winter driving. What would happen to Pauline in an accident, or, God forbid, if something happened to all of us?”

My cousins hate me. They play games with balls and I can't chase the ball. I complain to my mother and she makes them get it for me. Behind her back, my cousins call me “Tattle-tale.” I hate them every bit as much as they hate me.

But I have another aunt. She's the black sheep of the family and I adore her.

“Tante Marie isn't married,” I say. “You could ask Tante Marie.”

“You know how hard I find her visits. She interferes. She likes to stir up trouble.” My mother's nervous hands smooth her perfectly ironed skirt.

Tante Marie is my mother's youngest sister, ten years younger. Where my mother is hard bones and smells like a closed-up library, Tante Marie is soft skin and smells of lavender and the open woods. Her dark hair is never pinned back but curves playfully around her shoulders. She makes my father and me laugh and she's not afraid of anything or anybody.

Something always happens when she visits â some wonderful trouble.

There are only two weeks until Christmas.

My mother reaches for the top book. “The Secret Garden. You'd like it. There's a girl in this book almost as old as you and a boy in a wheelchair.”

She flips open to the first page.

I reach for my crutches, ignoring my brace. It takes too long to fasten around my left leg and I want to make a fast getaway. “I don't want to hear about a cripple.”

She starts to read, “When Mary Lennox was sent to Misselthwaite Manor to live with her uncle everybody said she was the most disagreeable-looking child ever seen ⦔

Without my brace, I lean heavily on my crutches to hurry out of the back room, into the front hallway. On my left is the kitchen. My mother's domain. On my right, stairs lead up to my parents' bedroom and the guestroom. I can't do stairs easily. My bedroom is here on the main floor, close to the side door. But my bedroom doesn't have a lock on it.

In front of me is the bathroom. It's my only choice. I lock the door behind me.

Her voice is slightly muffled. Too bad. I can still make out every word.

“So when she was a sickly, fretful, ugly little baby she was kept out of the way, and when she became a sickly, fretful, toddling thing she was kept out of the way also.”

I flush the toilet, over and over. For a while, all I can hear is the sound of water rushing through pipes behind walls and under the floor.

I stop. The last drips of water fill the toilet tank.

“There was panic on every side, and dying people in all the bungalows. During the confusion and bewilderment of the second day Mary hid herself in the nursery and was forgotten by everyone.”

I open the door a crack and thrust out my hand. “Okay. You win. I'll read it. But on one condition. You invite Tante Marie.”

There is the sound of a book being slammed shut. Pages pressing, words colliding. Trouble.

I feel the strong spine of the book placed between my thumb and fingers.

“Okay,” she says. “You win. I'll invite Tante Marie.”