Read In the Land of INVENTED LANGUAGES Online

Authors: Arika Okrent

In the Land of INVENTED LANGUAGES (7 page)

So, to sum up the progression from “let's make a math for language” to “let's make a hierarchy of the universe”:

To make a math for language, you need to know what the basic units of meaning are, and how we compute more complicated concepts out of them.

To figure both of these things out, you need an idea of how concepts break down into smaller concepts.

To break down the concepts, you need a satisfactory definition for those concepts; you have to know what things

are

.In order to know what something is, you have to distinguish it from everything it is not.

Because you have to distinguish it from everything, you have to include everything in your system. So there you are, crafting your six-hundred-page table of the universe.

Do you get the sense that each step in this progression doesn't necessarily follow from the last one? So did George Dalgarno. He was a Scottish schoolmaster of humble means who moved to Oxford in 1657 in order to start a school. After attending a demonstration of a new type of shorthand that could express phrases in “a more compendious way than any I had seen,” he was inspired

to “advance it a step further.” In the process of working out how to stuff the most meaning into the fewest possible symbols, he realized that such a system could be used not just as a shorthand for English but as a universal writing that could be read off into any language. He was “struck with such a complicated passion of admiration, fear, hope and joy” at this idea that he “had not one houres natural rest for the 3 following nights together.”

His idea wasn't as original as he thought. Quite a few scholars of the time had become preoccupied with developing a “real character.” This was the term used by the philosopher Francis Bacon to describe Chinese writing—it was “real” in that the symbols represented not sounds, or words, but ideas. Traveling missionaries of the previous century had noted that people who spoke mutually incomprehensible languages—Mandarin, Cantonese, Japanese, Vietnamese—could understand each other in writing. They got the impression that Chinese characters by-passed language entirely, and went right to the heart of the matter. This impression was mistaken (we will discuss how Chinese characters do work in chapter 15), but it encouraged a general optimistic excitement about the possibility of a universal real character.

Dalgarno was a nobody in Oxford, but it so happened that the only person he knew there, an old school friend, was in good with the vice-chancellor of the university. Dalgarno's work was read and passed around, and soon he found himself in the company of the most eminent scholars in town, a stroke of luck at which he was “overjoyed.” One of these scholars was Wilkins, who had not yet begun to work on his own universal character.

Dalgarno's system provided a list of 935 “radicals”—the primitive concepts he judged necessary for effective communication—

and a method for writing them. They were not, however, organized into a hierarchical tree. They were not grouped by shared properties, or by any logical or philosophical system. Instead, they were placed into a verse composed of stanzas of seven lines each, so that they could be easily memorized. For example, if you memorize the first stanza, you know the placement of forty-two of his radical words (italicized):

When I

sit-down

upon a

hie place

, I'm

sick

with

light

and

heatFor the

many thick moistures

, doe

open wide

my

Emptie

poresBut when sit

upon

a

strong borrowed

Horse, I

ride

and

run

most

swiftlyTherefore if I can

purchase

this

courtesie

with

civilitie

, I

care

not the

hirers barbaritieBecause I'm

perswaded

they are

wild villains, scornfully deceiving modest

menNeverthelesse I

allowe

their

frequent wrongs

and will

encourage

them with

obliging exhortationsMoreover I'l

assist

them to

fight

against

robbers

, when I

have

my

long crooked

sword.

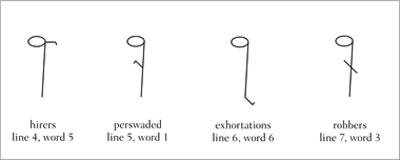

He developed a written character where the placement and direction of little lines and hooks referred to a specific place in a line of a stanza (as shown in figure 5.4).

To write “light,” for example, you draw the character representing the first stanza modified by a small mark indicating first line, fifth word. The pattern is repeated for the fourth through sixth lines, but with little hooks added to the marks, and for the seventh line the mark is drawn through the character (as shown in figure 5.5).

Figure 5.4: Dalgarno's system

Additionally, the opposite of a word was represented by reversing the orientation of the stanza symbol.

He also provided for a way for the system to be spoken by assigning consonants and vowels to the numbered stanzas, lines, and words. So if

B

= stanza 1,

A

= line 1, and

G

= word 5, then the word for “light” would be

BAG

.

Figure 5.5: Dalgarno's system, lines 4–7

Wilkins admired Dalgarno's system, but he thought it needed to include more concepts, and took it upon himself to draw up an ordered table of plants, animals, and minerals. Dalgarno respectfully declined to use those tables, arguing that the longer the list of concepts got, the harder they would be to memorize. He thought that specific species, like elephant, didn't need their own, separate radical words, but that they could be referred to by writing out compound phrases, such as “largest whole-footed beast.”

Dalgarno's method was another way to get a mathematics of language. No need to determine a universe of categories and distinguishing features—you simply decide what the primitives are (no need to systematically break everything down; just ask yourself what makes sense) and assume everything else can be described by adding those primitives together to make a compound. For Dalgarno, “coal” is “mineral black fire,” “diamond” is “precious stone hard,” and “ash tree” is “very fruitless tree long kernel.”

Wilkins thought this method lacked rigor. Dalgarno hadn't chosen his basic concepts in a principled way, and, worse, the words in his language told you nothing about their meanings, just their arbitrary placement in a nonsense verse. Wilkins was convinced

that the ordered tables were necessary. He wanted words to reflect the nature of things—only in this way could the language serve as an instrument for the spread of knowledge and reason. Dalgarno thought the tables were unnecessary. He wanted words to be easy to memorize—only in this way could the language be a useful communication tool. After about a year of arguing, they parted ways, and Wilkins began to work on his own project.

The Word

The Wordfor “Shit”

T

he problem with natural languages, as Wilkins saw it, was that words tell you nothing about the things they refer to. You must simply learn that a dog is a “dog” in English or a

chien

in French or a

perro

in Spanish or a

Hund

in German. The sounds in those words are just sounds to be arbitrarily memorized. They tell you what to call a dog, but they do not tell you what a dog is.

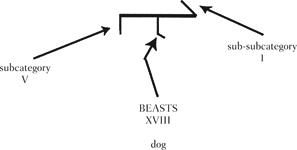

In Wilkins's system, the word for “dog” does tell you what a dog is. Like Dalgarno, Wilkins worked out a way to refer to a specific position in his tables with a character or a word. Since the concept dog is located in category XVIII (Beasts), subcategory V (oblong-headed), sub-subcategory 1 (bigger kind) (refer to figure 5.3), the character for “dog” would be formed with the symbol for category XVIII, along with modifications indicating subcategory V, and sub-subcategory 1.

The character for “wolf,” being paired with “dog” on the basis of a minimal opposition (docile versus not docile), requires an additional marking for opposite.