In The Royal Manner (19 page)

2.

Place the beef in the tin, push the onion close to the beef and the bay leaves under the beef. Roast for 10 minutes per 450g/1lb for rore beef; 12 – 15 minutes per 450g/1lb for medium to well done. Baste the joint occasionally to keep it moist. Transfer to a warmed serving platter, reserving the meat juices, cover and allow to stand for 30 minutes before carving.

3.

Meanwhile, make the Yorkshire puddings. Sift the flour with a pinch of salt into a bowl. Make a well in the centre, odd the egg and gradually incorporate the flour with the egg. As the mixture thickens, slowly pour in the milk, stirring until the mixture forms a smooth batter. Transfer to a jug and allow to stand for 30 minutes. Then re-whisk.

4.

Once the beef is cooked, spoon a little of the reserved beef cooking juices in a 12-hole patty tin and place in the oven for 2 – 3 minutes until very hot. Quickly pour in the batter and return to the oven and bake for 15 – 20 minutes until well risen and golden. Serve immediately.

5.

Carve the beef and serve with Yorkshire puddings. Herb Roast Potatoes (see page 53) and other roast and steamed vegetables. Accompany with gravy, horseradish sauce and English mustard.

SIRLOIN OF BEEF AND YORKSHIRE PUDDINGS

Mrs Beeton quotes a story about how sirloin got its name, crediting it to Charles II knighting the joint at Friday Hall, Chingford, Essex. The king returned from hunting in Epping Forest and saw meat.

‘A noble joint’, he said, ‘By George, it shall have a title?’. Then he drew his sword and tapped the meat, saying, ‘Loin, we dub thee knight. Henceforth be Sir Loin.’ Mrs Beeton says that the name is probably a corruption of the French

sur

(above) and

longe

(loin) into sirloin, the upper part of the loin, and though it is a pity to spoil a good story, this is probably correct. Yorkshire Pudding, a batter pudding created from a mixture of milk, flour and eggs, had been known in medieval times. Later it was made in a huge dish placed beneath spit-roasted meat so that the fat and juices would fall into the pudding pan and give it a unique flavour and appearance. It gets its name from its county of origin.

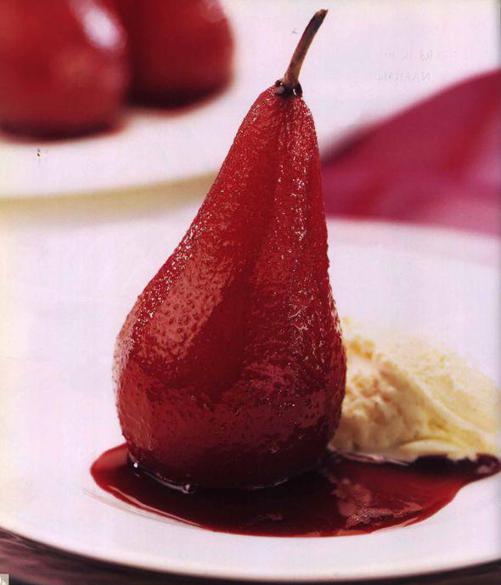

PEARS’

IN

PORT WINE

WITH

CINNAMON ICE CREAM

The simplest but most effective of all desserts. This was one of the Princess's favourites and was often served at official dinners and lunch parties.

Serves: 6

Preparation time: 1 hour plus standing, cooling and freezing

Cooking time: approx. 55 minutes

FOR THE ICE CREAM

450 ml/¾ pt single cream

1 vanilla pod

2 cinnamon sticks

3 medium egg yolks

100g/4oz caster sugar

150 ml/1¼ pt double cream

FOR THE PEARS

450 ml/¾ pt ruby port

1 strip lemon rind

1 strip orange rind

4 tbsp redcurrant jelly

2 cinnamon sticks, broken in half

6 ripe dessert pears

l lemon

‘Let the number of your guests never exceed twelve, so that the conversation might be general. Let the temperature of the dining room be about 68. Let the dishes be few in number in the first course but proportionally good. The order of the food is from the most substantial to the lightest. The order of the drinking is from the mildest to the most from and most perfumed. To invite a person to your house is to take charge of his happiness as long as he is beneath your roof.’

Mrs Beeton quoting ‘a great gastronomist’ in her Book of Household Management, 1859 – 61

1.

First make the ice cream. Pour the single cream into a saucepan. Split the vanilla pod down the middle and scrape out the seeds into the cream along with the pod. Break the cinnamon sticks into half and add to the cream. Slowly bring to a boil. Remove from the heat, cover and stand for 30 minutes.

2.

Whisk the egg yolks and sugar in a large bowl until pale, thick and creamy. Reheat the cream until gently simmering and then pour over the egg mixture, stirring constantly. Strain through a sieve back into the saucepan and cook over a low heat, stirring, until the custard thickens enough to coat the back of a wooden spoon. Do not allow to boil. Pour into a heatproof bowl and allow to cool completely.

3.

Whip the double cream until just peaking and then fold into the custard. Pour the mixture into a freezer container, cover and place in the coldest part of the freezer. Beat the mixture 3 – 4 times at 40-minute intervals to break up the ice crystals. Seal and freeze for a further 2 hours. Stand at room temperature for about 15 minutes before serving, to make sure it is soft enough to scoop.

4.

For the pears, pour the port into a saucepan along with 150 ml/¼ pt water. Add the citrus rinds, jelly and cinnamon. Bring to a boil and cook for 1 minute until the jelly has dissolved.

5.

Peel the pears, leaving the stalks intact. Slice the bottoms if necessary so that they stand up straight. Rub the cut side of the lemon over the pears to prevent them from browning.

6.

Stand the pears in a saucepan – you want them to stand snugly next to each other – and pour over the hot port. Bring back to a boil, skim away any surface scum, cover and simmer for 35 – 40 minutes, spooning the cooking liquid over the pears frequently, until tender.

7.

Remove the pears using a draining spoon, reserving the cooking liquid, and place the pears in a heatproof dish. Return the cooking liquid to the heat and bring to a boil. Cook for 12 – 15 minutes until well reduced and syrupy. Pour the syrup over the pears through a sieve, and allow to cool, then chill for 1 hour before serving with cinnamon ice cream. Alternatively, serve hot with the ice cream.

Cook's note:

it is vital that you use fresh spices for this recipe, otherwise there will be little flavour. Cinnamon bark has a very delicate flavour that is soon lost in storage.

PUNCH JELLY

Another popular dessert with the Victorians was an extremely alcoholic jelly made of rum and brandy. It was flavoured with orange and lemon and the spices cloves, nutmeg and cinnamon. The liquid was sweetened and set with gelatin. It was often poured into small punch cups or a beautiful jelly mould and allowed to set. Only a small portion was suggested, as it really did pack a punch!

Serves: 12

Preparation time: 15 minutes plus cooling and setting Cooking time: 20 minutes

225g/8oz caster sugar Finely grated rind of 3 lemons

Finely grated rind of 1 orange

5 cloves

Pinch of grated nutmeg

1 cinnamon stick, broken

150 ml/¼ rum

150 ml/¼ pt brandy

150 ml/¼ pt fresh lemon juice

1/l tbsp powdered gelatin

1.

Place the sugar in a large saucepan with 600 ml/1 pt cold water. Add the lemon and orange rind and spices. Bring to a boil, stirring, until dissolved and then simmer for 15 minutes.

2.

Remove from the heat and pour in the rum, brandy and lemon juice. Strain the mixture through a sieve lined with muslin into a heated bowl.

3.

Dissolve the gelatin in 5 tbsp boiling water and stir into the strained liquid. Set aside to cool and then pour into a 1 lt/1¾ pt jelly mould or 12 punch glasses or small dishes and chill until set. Serve decorated with slices of lemon.

CLASSIC VICTORIAN FOODS

It you want to put together your own Victorian-style menu, you might find this table of food suggestions useful for ideas:

MAIN COURSES

turtle soup, truffles, pheasant, prawns, grouse pie, lobster, ham, tongue, roast beef, fillet of veal, mutton cutlets, sweetbreads, aspic jellies. Asparagus was a popular vegetable

SWEETS

compotes of fresh and dried fruits, candied fruits, jellies, fruit tarts, bavarois, iced desserts

CHEESE

Stilton

DRINKS

barley water, hot and cold punches, fresh lemonade

Tea epitomizes the British way of life. From Buckingham Palace to a terraced home in the heart of England, a cup of tea is the greatest of all British traditions. Whether the tea is loose leaf Darjeeling, Earl Grey or a simple tea bag, this revitalizing and comforting brew is served in just about every household and workplace throughout the country, and it has been a tradition for many years.

Whether enjoying tea in your home, in a country garden or at a formal occasion, it is guaranteed to provide refreshment. There is always time for a ‘cuppa’, and at times of crisis there is always a cup of tea on hand for comfort.

By the end of the 19th century some households, because they did not take luncheon, brought their evening meal forward to fill the gap. In the north of England this became known as ‘High Tea’ and it centred round the drinking of what had previously been a cup of tea or on afternoon drink. In households where dinner was served later, a light meal was introduced which was often the last meal the children would have before they went to bed. At first it was just a cup of tea and a sandwich, but gradually a wider variety of cakes and fruits were added. The emergence of tea as a social event was born, and it is often associated with gossiping women in the drawing rooms of Victorian England. In 1877 the tea gown was devised as a fashionable garment suitable for such an occasion.

Taking tea at five o'clock is still a tradition observed by the Royal Family wherever they are in residence, and the Queen delights in making her own pot of tea, in a silver teapot, of course.

‘A woman is like a tea bag: only in hot water do you realize how strong she is!’

Nancy Reagan

During my career, I must have served thousands of cups of tea at receptions, meetings and garden parties and this is my tried and tested way of making the perfect cuppa. The essential element of course, is boiling water.

1.

Warm the teapot with boiling water. Always take the pot to the kettle, not vice versa. After 2–3 minutes pour the water away.

2.

Spoon one teaspoonful of tea per person plus ‘one for the pot’ into the teapot – this does depend on the strength of tea, size of teapot and personal taste.

3.

Pour over boiling water until the pot is three quarters full. Leave to ‘steep’ for 2 – 3 minutes, stirring once to ensure the leaves infuse properly.