In the Sanctuary of Outcasts (7 page)

Read In the Sanctuary of Outcasts Online

Authors: Neil White

My menu board illustrations had become popular with the leprosy patients. They especially liked my President Clinton caricatures. So I added more colorful illustrations and entertaining slogans to each day’s board. When the meal included Cuban Chicken, I sketched a portrait of Fidel Castro smoking a cigar, holding a chicken by the neck. On Mexican Day, I designed the text to fit inside a large sombrero, and I added Taco Bell’s slogan, “Make a run for the border.” The inmates and leprosy patients thought it was pretty funny; it didn’t amuse the warden nearly as much.

To get a jump on my early morning duties, I started to transcribe the menu board in the patient dining room every day after lunch. As I wrote on the board one afternoon, I heard a voice behind me announce, “Hey, they finally gave us one who can spell!” A gaunt black man wearing a hat and a khaki coat reached out to shake my hand. “I’m Harry,” he said with a crooked smile, “nice to meet you.” He looked like the man I saw waving through the screen on my first day. His hand had only two appendages—a complete thumb and part of an index finger. His other digits looked like they had been absorbed or maybe burned off. He seemed friendly. I didn’t want to reject him, especially since my own hand had been twice refused. But I didn’t want to touch him either. And how would I do it? Grab his finger and shake? Put my open hand between his thumb and index finger and let him grab on?

He noticed my hesitation. Harry’s smile disappeared. He put his

hand back in his coat pocket. “You’ve got real neat handwriting.” He smiled again and told me to have a nice day. I looked around the room and saw the other patients. They exchanged glances and shook their heads. As I watched Harry walk away, I knew I had hurt his feelings. I wanted to call him back, apologize, and accept his hand.

But it was too late.

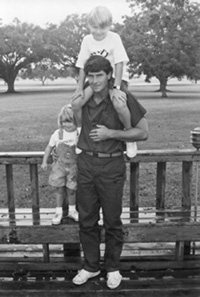

Little Neil, Maggie, and me on the visiting room deck.

“May I

please

borrow your iron?” I asked again.

CeeCee had no intention of giving up her iron. CeeCee was a federal inmate, too, but she insisted that we use feminine pronouns when speaking to, or about, her. CeeCee’s shirt collar was turned up around her thin neck. The top four buttons on the tight green shirt were left open to reveal what would have been cleavage had she been a woman. I guess she figured our deprived imaginations would fill in the rest. CeeCee had altered her prison-issued slacks to look like capri pants.

“Nobody touches my iron,” CeeCee said, with a hand cocked on her hip.

My shirts were wrinkled, and Linda and the kids would arrive in the visiting room in less than an hour for our first visit.

CeeCee offered to iron my shirts. She said she would charge twenty-five cents per shirt, and she promised to have one pressed and ready by the time my family arrived. She bragged that she could iron pants better than a professional dry cleaner, that her shirts held up for days, even in the Louisiana humidity, and that she would even sew a Polo man onto the left breast pocket. “I can add starch,” she added.

I loved starch. I had always requested heavy starch at the cleaners. My shirts and pants were as stiff as cardboard. Starched clothes looked old-fashioned and stable. My clothes reminded older businessmen around town of a simpler, more genteel way of life. And I liked that.

I paid CeeCee in quarters and asked her to hold off embroidering the Polo man.

Two weeks had passed since Linda dropped me off at the colony gate. Anxious, in my perfectly pressed prison uniform, I stood in the hallway with the other inmates. We gathered behind a barricade the guards set up on visiting days. As families arrived, a guard would escort us to the visiting room to reunite with our wives and children.

Linda was late. After waiting about an hour, I started to worry. Maybe she’d had a hard time getting the kids ready by herself. I couldn’t help wondering if something had gone wrong. An accident. A flat tire. A family emergency. I felt helpless. I did the only thing I could do. I waited.

One other inmate had been waiting just as long. He said I shouldn’t be disappointed if my family didn’t show up. Sometimes, he said, they just can’t face another trip to a place like this.

The guard finally called my name. As I walked to greet Linda and Neil and Maggie, I hoped my children wouldn’t be shaken by seeing me in jail, as an inmate, in a prison uniform. I didn’t know how I would explain an inmate cursing or stealing. Or, God forbid, if they encountered a leper. How would I explain these things to a six-year-old and a three-year-old?

In the visiting room, my inmate friends were already settled in with their families. Doc sat at a round table in deep conversation with his girlfriend, a former nurse. Chief, a Native American inmate with long, silver hair, played a card game with his grown son. Steve Read, an airline entrepreneur, held hands with his wife, who looked like she was ready for a fashion shoot. Other families played dominoes or cards, like they had nothing better to do with their time.

My family stood next to the toddler play area. Neil and Maggie ran toward me. I bent down and hugged them both tight. They yelled that they wanted to go down the slide on the playground. I hugged Linda, and she gestured for me to go outside with the kids. She would wait on the deck. “We can talk later,” she said.

Maggie, Neil, and I played a makeshift game of baseball using imaginary bats and a racquetball, but the kids quickly grew bored. Little Neil had a better idea. He had been through one judo lesson in New Orleans. He grabbed my shirt and tried to flip me. I fell into his move so that I ended up on my back, sprawled on the grass.

An armadillo waddled toward the playground like a tiny prehistoric creature protected by nine bands of armor. It sniffed around the fence and then wandered off toward a ditch. I noticed the leprosy patients were out enjoying the morning too. Harry rode his bike along a concrete path. An overweight patient passed us in his cart driving toward the golf course. A woman with one leg zipped by in an electric wheelchair. For the most part, the patients ignored us. But one stopped and stared. Anne. She looked in our direction and stood with her hands on her hips. I struggled up from the ground and wiped the grass from my pants.

In her midsixties, Anne had a narrow face and dark circles under her eyes. Her hair was dyed black. When she was first quarantined at Carville, away from her family and alone, she fell in love with one of the other patients. A few months later she discovered she was pregnant. Anne knew the policy. Everyone did. It was simple, and cruel. Babies born to women with leprosy were taken away immediately and put up for adoption. It was possible for a quarantined woman to make arrangements with her extended family to care for the child, but like so many at Carville, Anne had been disowned. As far as her family was concerned, she was dead. No one in her family would take the child.

On the day Anne’s daughter was born, one of the nuns, a Sister of Charity, assisted with the birth. She washed and weighed the child. Then she wrapped her in a blanket and placed her in the wicker basket the Sisters had used for decades to transport the children born to leprosy patients.

Anne called to the Sister, “I want to see my baby.”

In the room next door, the nun collected the baby girl from the basket. She stopped at the doorway of the birth room and held the baby up high.

“I want to hold her,” Anne said, but the rules were clear.

The nun cried as she pulled Anne’s baby next to her own breast and turned away.

Just outside the prison visiting area, Anne watched as dozens of imprisoned fathers played with their sons and daughters. She was confronted with all she had missed. Even convicts were allowed to hold their children.

One of the other inmates on the playground noticed me watching Anne. “Surreal, isn’t it?” he said.

I nodded and looked over at my children. Neil practiced his judo moves on Maggie, who seemed perfectly happy to be flipped onto the ground and repeatedly fallen upon.

“First visit?” the inmate asked.

I nodded.

“Always tough,” he said, “especially on the wives.” His own daughter was seven. He considered himself fortunate. Inmates with teenage children, he said, had a more difficult time. Older kids seized on the fact that their fathers had broken the law and, consequently, had no right to tell them what to do. “Young ones don’t know any better,” he said. “They figure all daddies do a little time.”

I warned Neil to be careful flipping Maggie. She jumped up and said, “Daddy! I know judo, too!” Then she lurched forward and delivered a head butt directly to my crotch. Maggie smiled. She was proud that her move had bent me over. I patted her on the head and told her I thought she had a great future in the martial arts. One of the other kids asked Neil and Maggie to join them on the pirate’s ship.

I saw Linda on the wooden deck. She sat alone and stared out at the colony. She looked sad, and it was my fault. Neither one of us wanted to be here. And we were both at a loss for words.

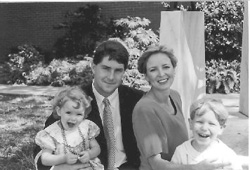

Maggie, me, Linda, and Little Neil

(left to right)

in the courtyard at St. Peter’s by-the-Sea, Easter 1992.

I met Linda in Oxford, Mississippi, in 1984 when we were both hired at Syd & Harry’s, a new restaurant that promised to change the way the small town experienced fine dining. We were both twenty-three years old. Before I met Linda, I had dated pageant girls. In Mississippi, they are everywhere: young women who spend an inordinate amount of time on makeup, hair, exercise, fashion, diet, and posture. I endured constant talk of calories and minute weight gain because the girls made me look good. To walk arm in arm with a girl who was always onstage, aware—or at least imagining—that people were constantly looking, did wonders for my image.

Linda was different. She was as attractive as any of the pageant girls, but she would never have degraded herself by allowing beauty pageant officials to judge her appearance. Her light blond hair perfectly framed her taut olive face. Her nose formed a flawless angle above thin lips that revealed a bright and spontaneous smile.

Her loveliness matched her demeanor. In everything, moderation. A bit of each day spent outside with family, with a book, at a good meal, with a glass of wine—at the most, two. At the best restaurants, she would take four or five bites of the entrée and lean back, satisfied. She would say it was one of the best meals she could remember. Of course, I would finish mine, and eat the rest of hers, too.

When we met, Linda was a graduate student in literature and creative writing. I had assumed she’d come from a home where education and enlightenment had been handed down through generations.

But she came from a family of Mississippi farmers. She was the first in her family to graduate from college.

Her relatives had treated me like blood kin. Her grandfather, a dirt farmer who amassed a fortune over the years, invested $10,000 in my newspaper business. After my terrible stewardship of his money, and everyone else’s, he spent another $5,000 to help retain my criminal lawyer. He kept no ledger when it came to family. There were no debts. Only gifts. When I asked how I could ever repay him, he said in a soft southern drawl, “Do the same thing for your children.” As I awaited my criminal sentence, he pulled me to the side and asked, “Does the judge have a price?” Then he winked and put his arm around me. We both knew he would never break the law, but he wanted me to know that if he were that kind of man, he would have done it for me.

In my mind, Linda was just about perfect. Attractive. Smart. Petite. Quick-witted. The kind of woman people wanted to be near.

We left Oxford for our honeymoon under an awning of brilliant, yellow ginkgo leaves. That evening at the Ritz-Carlton in Atlanta, with its polished wooden walls and ornate antiques, the clerk handed me two keys. One for the room, the other for an honor bar.

As Linda bathed in the opulent marble tub, I unlocked the bar and tore into the Godiva chocolates and imported nuts. I opened a bottle of Moët & Chandon, and then a bottle of red wine, then a bottle of white, just in case she preferred it to champagne. I scattered M & Ms and caramel squares and imported candies on the bedside and coffee tables. Linda stepped into the room in her robe, fresh from her bath, ready to consummate our marriage. Her skin was smooth and lucent. I could smell the lavender bath oil from where I sat in an overstuffed chair, my mouth full of macadamia nuts. She saw the pile of empty wrappers, corks, and foil. She glanced over at the open bottles and the mounds of candy.

“Look, honey,” I said, “they have this great bar in our honor.”

Under her breath Linda said, “I’ve made a mistake here.”

We loved to tell the honor bar/honeymoon story. We had laughed about it a hundred times with friends and family. And when Linda

laughed without reserve, small dimples on her cheeks exposed a tenderness underneath her regal air. I hadn’t seen the dimples in more than a year. Now, on the deck of a prison visiting yard, we didn’t have much to laugh about. I sat down next to her and held her hand. “How are you?”

She forced a smile and glanced down at the ground below. At the entrance to the prison, a guard had waved a handheld metal detector over Linda’s entire body. Then he did the same with the children. One of the female guards said that Linda’s sundress, a dress she had worn to church, was too revealing, too low cut. The guard added that she would be turned away in the future if she arrived in anything like it.

Linda was mortified. She had done nothing wrong. Except marry me. The last year had been a series of humiliations. Bankruptcy. Criminal hearings. Newspaper headlines about my prison sentence. A front-page photograph of the two of us, with Linda prominently featured in the foreground. Expulsion from private clubs where our friends still gathered.

I had convinced Linda early in our relationship that together we were going to make a difference. With her talent and refinement, and my drive and salesmanship, we could conquer any task. I was confident and self-assured—very different from her father—and I knew she was drawn to that trait in me. I asked her to join me in building a publishing empire that would bring with it influence and power, money and prestige, and lead us to places neither could quite imagine. The details of our conquests were not fully developed, but I assured her that the ride would lead in one direction. Up.

We sat among the other inmates. The words came hard.

I told her about Doc and Link and Frank Ragano and CeeCee and other interesting inmates I had encountered. I left out the stories about the leprosy patients. I told her every funny incident I could remember. I hoped to see a glimpse of her dimples. But she couldn’t muster much of a smile.

“I’m glad you’re having a good time.” She shook her head. “I’m sorry. That came out wrong.”

But it didn’t. She was bearing the brunt of things now. She lived

outside. She had to face the stares from neighbors, from other moms in the carpool line. She answered phone calls from creditors. She overheard the talk about how much money I’d lost and about how many people I’d hurt.

“I’m so sorry,” I said. “So sorry I put you and the kids in this situation.”

Linda was tired of my apologies. I had said

I’m sorry

so many times it didn’t carry much weight now.

“If you’re really sorry,” she said gently, “you’ll change.”

I knew she was counting on that. If I could change, she had told me, she might be able to take me back. But I didn’t know how to change. And, secretly, I didn’t think I needed to. I didn’t want to become a different person. I simply needed to operate within the bounds of the law. I wasn’t about to let go of the skills I’d developed or the plans I’d made. And I had a new plan as an undercover reporter that was going to secure my future. But I didn’t tell Linda. At least not yet. No need to get her involved. Plus, she might not have liked the idea.

Little Neil grabbed my hand and pulled me toward the playground. The racquetball had bounced over the fence and stopped about ten feet outside the perimeter.

“Go get it, Dad,” Neil said. Maggie stood next to him and pointed at the blue ball. They waited for me to step over the three-foot fence and get the ball. I looked around. A guard was watching me from the deck. It had been made clear to the inmates.

If you go outside the fence, you lose visiting privileges

.

For as long as my children could remember, I had ignored fences and boundaries and rules. I climbed buildings to get balls out of gutters. I jumped curbs to get closer to the entrance of football games. I talked clerks into giving us rooms at overbooked hotels. Nothing much had prevented me from getting what I wanted, and I made sure my children knew it. Now I stood at the edge of a knee-high fence, embarrassed to be so helpless.