Independence (14 page)

Authors: John Ferling

With expressive eyes and soft features, Galloway’s countenance was appealing, but he was not an expansive or approachable person. To all but his closest friends, Galloway came across as stiff, austere, and unreachable, though his manner was not entirely a liability in the sometimes stuffy, premodern world of colonial politics. His unflagging industry was crucial to his political ascendancy, as was his unquenchable ambition. Galloway’s drive could make him hard and ruthless in the assembly’s political brawls. His tart manner once led him and his acrid rival John Dickinson to engage in fisticuffs. One of Galloway’s greatest assets was his unmatched skill as an orator, a talent he had honed before innumerable juries and which was so exceptional that his fellow assemblymen called him the “Demosthenes of Pennsylvania.” Galloway’s wife thought him an honest man, though naive in his personal and political relationships. Possibly thinking of her husband’s relationship with Franklin, she subsequently remarked that he had often been undermined by those whom he regarded as his friends. Galloway’s only child, a daughter who was entering adolescence in 1774, knew him as a doting father. While his political enemies acknowledged that Galloway was “sensible and learned,” they also impugned him as pushy, haughty, and egotistical. He habitually chased after “eternal Fame,” they charged, and daily sought to make his social inferiors aware of his overarching supremacy and their lowly subservience. After meeting the Pennsylvanian once or twice, John Adams wrote that Galloway comported himself with an “Air of Reserve, Design and Cunning.”

17

Without Franklin, Galloway might not have risen so far or so fast. On the other hand, without Franklin he may not have fallen so far and so hard. Franklin and Galloway probably met in the early 1750s. It is possible that they were first brought together by Franklin’s son, William, who was a close friend of Galloway and a fellow lawyer. However, in a city the size of Philadelphia—it had about twenty thousand inhabitants in the 1750s—it is hardly surprising that the paths of two such active and ambitious men would cross. Franklin was the first of the two to enter politics, but once Galloway was elected to the assembly, each must have rapidly glimpsed potential advantages through collaboration. Franklin made Galloway his legislative assistant in 1756. By the next year they were full-fledged partners, jointly running the Assembly Party, which controlled the Pennsylvania assembly for most of the next two decades. With Franklin abroad much of that time, the party itself was controlled by Galloway, who year in and year out served as the speaker of the house.

18

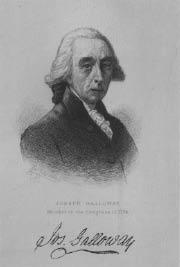

Joseph Galloway by Max Rosenthal. This depiction shows an older and harder Galloway, as he may have appeared in 1774. He refused to serve in Congress after hostilities broke out and he died in exile in England. (Print Collection, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, New York Public Library)

The Assembly Party managed Pennsylvania’s war efforts during the French and Indian War, and as hostilities died down after 1759, it turned its attention to making the province a royal colony. It is difficult to escape the conclusion that the principal impetus for the party’s campaign was Franklin’s hope of becoming the royal governor of Pennsylvania and Galloway’s longing to climb the political ladder, perhaps starting as a Crown-appointed magistrate and ending who-knew-where. For Galloway, his single-minded focus on royalization, together with his personal and political shortcomings, would in the long run prove to be a toxic mix.

19

By the time word of the Stamp Act reached Philadelphia in 1765, Galloway, cheerily optimistic as always, was convinced that Pennsylvania soon would be a royal province and that Franklin’s appointment as governor was imminent. To assure success, he believed that he had to keep Pennsylvania in “every way moderate.” He could not prevent Philadelphia’s fiery protests against the Stamp Act, but with Dickinson’s Proprietary Party leading the opposition to parliamentary taxation, Galloway unwisely made the Assembly Party into a cheerleader for Britain’s new policies. Spokesmen for the party aspired “to state the Conduct of the Mother Country in a true Light” and to demonstrate the “reasonableness of being Taxed.” Galloway himself portrayed the foes of the Stamp Act as “wretches” and “Villains,” and he publicly defended Britain’s “Good Disposition towards America.” At the very moment that Franklin was testifying before the House of Commons on behalf of repealing the Stamp Act, Galloway wrote to him boasting that the Assembly Party had been “the only Loyal Part of the People.” It alone had “oppose[d] the Torrent” and sought to “discredit” those who denounced the law.

20

With Franklin dropping hints from London that Hillsborough and others in the ministry were favorably disposed toward Pennsylvania’s royalization, Galloway and the Assembly Party stood foursquare behind the Townshend Duties in 1769 and 1770. Even as the colony embraced a trade embargo and Franklin surreptitiously attacked the new taxes in London newspapers, Galloway told his political partner that he was working to assure Pennsylvania’s “Dutiful Behaviour during these Times of American Confusion.” Galloway’s actions were tantamount to political suicide. By October 1770, when the annual assembly election was held, the Assembly Party was anathema in Philadelphia. Galloway, who had been elected to one of the city’s eight seats in the assembly for fifteen years, had to run in rural Bucks County to win reelection.

21

Despite its collapse in Philadelphia, the Assembly Party remained in control of the assembly until 1774. It survived because it remained the overwhelmingly dominant faction in rural eastern Pennsylvania, a region with 50 percent of the colony’s population but nearly three quarters of the allotted seats in the assembly, and Galloway continued in his post of speaker. Though hardly powerless, his loss of popularity in Philadelphia weighed on Galloway, and for a time in the early 1770s he contemplated abandoning politics.

22

During the same period, perhaps concluding that his troubles had mounted because of his naive trust in Franklin, Galloway drifted away from his old partner. While Franklin wrote to him several times each year, Galloway answered with only three letters in the forty-eight months after January 1771.

Galloway remained politically active, but he changed course after 1771. Among other things, he abandoned his open defense of parliamentary taxation, emphasizing instead the benefits that the colonists derived from their connection with Great Britain. Galloway and others among the most conservative Americans increasingly stressed that the colonies were an extension of British civilization, nourished and protected by the mother country. They asserted that the British and the Americans not only were the freest people on the planet both politically and religiously but that the colonies also prospered from imperial trade. Pointing to the vast quantities of British manufactured goods that were consumed annually by Americans, they portrayed the Anglo-American union as “a commercial Kingdom.” However, it was not only material plenty that made the empire desirable. The existence of a strong, central imperial government assured stability and the rule of law in America. The many benefits of empire had made the colonists “the happiest People … under the Sun.” But, conservatives warned, all was threatened by the colonial dissidents.

23

If the American radicals pushed the imperial crisis to the point of American independence, social revolution would be the result. Even conservatives who resisted parliamentary taxation and the extension of British hegemony shared this view. For instance, New York’s Gouverneur Morris—who would support the Revolution and ultimately sit in the Constitutional Convention in 1787—warned in the early 1770s that “the mobility [the upwardly mobile patriots] grow dangerous to the gentry.” It was in the interest of the most affluent Americans, Morris added, “to seek for reunion with the parent State.”

24

After 1770, Galloway’s mission was to save the Anglo-American union, but even he understood that it could not endure in a relationship in which Parliament claimed the right to legislate for the colonists in all cases whatsoever. Accordingly, Galloway denounced Britain’s dissolution of the New York assembly and asserted that only the colonial assemblies could tax the colonists. There can be no “Union either of Affection or Interest between G. Britain and America until … there is a full Restoration of its [America’s] Liberties,” he proclaimed. Inching toward some sort of compromise solution to the imperial woes, he also excoriated the colonists’ growing distrust of Great Britain as “mad.”

25

In 1773, Galloway neither defended the Tea Act nor made an effort to have the cargo aboard the

Polly,

the tea ship bound for Philadelphia, unloaded and sold. When London answered the Boston Tea Party with the Intolerable Acts, Galloway immediately understood that American resistance meant war. However, his response was not politically adroit. Once Paul Revere’s sweaty mount galloped into Philadelphia in May 1774 carrying Boston’s appeal for a national boycott of British trade, Galloway led the fight against another trade embargo. He did so as much from the fear that an embargo would lead to war as from the hope of saving Philadelphia’s merchants from additional grievous losses. Galloway was swiftly outmaneuvered. The city’s radicals organized a mass rally that called for both a boycott and a continental congress. Galloway at first opposed both steps and refused to convene the assembly, which ultimately would have to decide Pennsylvania’s response to Boston’s entreaty. In mid-June the radicals struck with yet another outdoor meeting attended by thousands in downtown Philadelphia. The gathering endorsed the idea of summoning an extralegal assembly into session, seemingly the only means by which Pennsylvania might be represented in a continental congress. Faced with the prospect of a revolutionary body—one that would surely give proper representation to the western counties that long had been underrepresented in the Pennsylvania assembly, and which would supplant the colony’s legitimate legislature—Galloway caved in.

26

He called the assembly into a special session. By the time it met, Galloway knew not only that a continental congress was inevitable but also that New York’s conservatives had agreed to such a meeting in the hope of restraining New England’s firebrands. Galloway suddenly saw an opportunity to act in concert with other delegates from the mid-Atlantic region, and perhaps elsewhere. Thus, when the Pennsylvania assembly met, it agreed, under the guidance of Galloway, to a continental congress and proposed that it be held in centrally located Philadelphia early in September. The assembly also elected seven delegates to the congress, all conservatives and moderates. Galloway was included in the delegation, and he saw to it that his old rival Dickinson, next to Franklin the most popular Pennsylvanian, was not chosen. The assembly instructed its delegates to “establish a political union between the two countries,” Great Britain and its American colonies.

27

A day or two later, one of Pennsylvania’s delegates, Thomas Mifflin, a Philadelphia merchant, informed Samuel Adams that his colony would vote to boycott British trade only if “some previous Step” was taken by the congress to peacefully resolve the crisis.

28

Neither Samuel Adams nor Joseph Galloway had initially desired a continental congress, but in the end both accepted it. For Adams, a national congress offered the only hope of obtaining a national boycott of British trade and, perhaps, of preparing for war. For Galloway, if it acted with what he called “Temper and Moderation,” a national congress that spoke for America would subsume “the illegal conventions, committees, town meetings, and … subservient mobs” that Adams and his ilk had controlled.

29

Moreover, as the heat-blistered summer of 1774 set in, Galloway had come to believe that an intercolonial congress offered the best hope, if not the only hope, of preventing war.

From the southern low-country to northern New England, the delegates to what became known as the First Continental Congress—fifty-five men in all—descended on Philadelphia in August and early September. Most traveled by carriage and in the company of other delegates. The four congressmen from Massachusetts, together with their four servants, met on August 10 at Thomas Cushing’s residence in Boston and set out from there. Three weeks later Patrick Henry and Edmund Pendleton stopped at Mount Vernon to pick up George Washington. Accompanied by slaves, they started the long, dusty journey to Pennsylvania on a day that Washington described as “Exceeding hot.”

30