Independence (24 page)

Authors: John Ferling

Thus, by nine A.M., when the redcoats at last marched into Concord under a bright sun high in a blue sky, the residents had known for several hours that they were coming. Nevertheless, the regulars marched into the village unopposed. Colonel James Barrett, the Middlesex regimental commander who was the officer in charge of the five trainband companies that were present in Concord—probably a bit fewer than two hundred men—found himself, like Captain Parker, badly outnumbered and unwilling to order his men to resist the king’s troops.

The regulars set right to work destroying the arsenal. During their first hours in town, few of the hardworking, sweaty soldiers saw the Concord militia, which remained passively on its muster field across the Concord River, nearly a mile away. As the morning progressed, Concord’s militiamen were joined by minutemen who arrived from neighboring towns. Slowly, steadily, the American force grew. By midmorning nearly five hundred militiamen were present. Wired and eager for a fight, some pleaded with Colonel Barrett, a sixty-year-old miller who had taken the field this day wearing his soiled leather work apron, to do something. Still outnumbered, Barrett refused to budge. But around eleven A.M. the militiamen spotted black smoke curling above the bare trees in Concord. Though the regulars had torched only ordnance in the arsenal, word spread like wildfire that the British army was burning the town. Barrett could wait no longer. He ordered his men to load their pieces and march to the North Bridge that spanned the river. The Americans found 115 redcoats guarding the bridge on the other side. Men on both sides were jittery and armed, a dangerous combination. The lead element among the militiamen crowded onto the bridge and moved forward. As the rebels advanced, a shot rang out. This time there was no mistaking its source. A British soldier had fired his musket. As had happened at Lexington, the sharp, jolting sound of the shot caused men on both sides to open fire. The exchange was brief but deadly. Six Americans were wounded, two fatally. One who died was Captain Isaac Davis, an Acton farmer who had built a firing range behind his house to hone his skills as a marksman; he was shot through the heart in the first nanosecond of his combat experience. Twelve regulars were cut down by the return fire of the rebels. Three suffered mortal wounds, the first of the king’s soldiers to perish at the hands of colonists.

The regulars at the bridge fled after one volley, joining their comrades in town. Colonel Smith had long since known that the hoped-for secrecy of his mission had been lost. With the arsenal nearly destroyed, and faced with a march to Boston that would require hours, he immediately abandoned further work in Concord and set his force on its return home. Throughout that golden afternoon, a seemingly endless stream of American militiamen arrived and took up positions along bucolic Concord Road. Before the sun set, men from at least twenty-three Massachusetts villages were present and fighting, and their numbers had swelled to almost three thousand, providing the colonists with a considerable numerical superiority. Firefights raged up and down the road. Militiamen, concealed behind stone walls, trees, barns, and haystacks, laid down a triangulated fire on the retreating regulars. It was a bloodbath, and only the arrival of redcoat reinforcements summoned after the skirmish in Lexington prevented the killing or capture of the entirety of Smith’s original force.

War brings out the best and the worst in people. Catherine Louisa Smith, Abigail Adams’s sister-in-law, who lived about halfway between Concord and Lexington, helped a badly wounded grenadier into her house and tried to nurse him; the soldier died and was buried on the Yankee farm.

51

Heroism was displayed by the fighting men on both sides, but wanton cruelty was in evidence as well. Victimized by snipers who fired from inside houses, contingents of regulars at times stormed dwellings in search of partisans. When the soldiers invaded a home, they often gave no quarter. Those who entered the houses following the battle sometimes found bodies strewn about, and one witness exclaimed that the butchery in one residence was so immense that “Blud was half over [my] Shoes.” Others reported finding civilians who had been stabbed, bludgeoned, and shot, and one told of discovering the inhabitants’ “brains out on the floor and walls.” Not infrequently, the king’s soldiers plundered and burned houses and killed livestock.

52

As darkness spread over the blood-soaked landscape, the regulars at last reached Boston, and safety. By then, 94 colonists were dead or wounded. The British army had suffered 272 casualties. Dartmouth had said in his order to use force that Gage should not expect much opposition. Sixty-five of Gage’s men lay dead at day’s end on April 19.

53

As that cold, gray spring of 1775 little by little crept toward disaster, George Washington, who was more than a thousand miles removed from Lexington and Concord, frequently hunted, passionately landscaped Mount Vernon, and oversaw the preparation of his fields for the season’s crop of wheat.

54

He had returned home from Congress doubting that war was likely, but the imperial crisis was never far from his thoughts.

Washington had attended the Continental Congress persuaded that North’s ministry was advancing “a premeditated Design and System … to introduce an arbitrary Government into his Majesty’s American Dominions.” He had thought of the Tea Act and Coercive Acts as “despotick Measures” that were part of a “regular, systematic plan” to “fix the Shackles of Slavery upon us.” No less important, Washington had come to understand that Britain had “a separate, and … opposite Interest” from that of the colonies. He had openly stated that the colonies must be “treated upon an equal Footing with our fellow subjects” in England under a “just, lenient, permanent, and constitutional” framework.

55

He was fed up with “Petitions & Remonstrances” even before Congress met. Truth be told, he probably already favored American independence. What seems abundantly clear is that long before the march on Lexington and Concord, Washington had been prepared to go to war unless the British government backed down.

56

The events in Lexington and Concord made it apparent that London would not back down. Washington was convinced that the colonists must not give in. A “Brother’s Sword has been sheathed in a Brother’s breast,” he immediately declared when word of the carnage in Massachusetts reached Mount Vernon late in April. He added that the “once happy and peaceful plains of America are either to be drenched with blood, or Inhabited by Slaves.” His choice was never in doubt. Indeed, he emphasized that no “virtuous Man” could “hesitate in his choice.”

57

Washington departed Mount Vernon for Philadelphia and the Second Continental Congress on May 4, 1775, taking with him his military uniform. He was going to war. Unlike Dartmouth and North, Washington harbored no illusions that this would be an easy war. “[M]ore blood will be spilt” in the coming conflict, he predicted, “than history has ever yet furnished instances of in the annals of North America.”

58

CHAPTER 5

“A R

ESCRIPT

W

RITTEN IN

B

LOOD

”

J

OHN

D

ICKINSON AND THE

A

PPEAL OF

R

ECONCILIATION

IT TURNED COLD AND RAINY

overnight in Boston, but all through the jet-black evening that followed the battle-scarred day in Lexington and Concord, armed men from throughout New England had descended on the city. Some had abandoned workbenches and farms on a moment’s notice to take up arms. Israel Putnam, for instance, a fifty-seven-year-old yeoman who had endured a lifetime of adventure while soldiering in the French and Indian War, literally dropped his plow in his field in Pomfret, Connecticut, picked up his sword and musket, and headed for the scene of action, ready to serve yet again. One company of exhausted minutemen from Nottingham, New Hampshire, arrived outside Boston at daybreak on April 20, having made an incredible fifty-five-mile march in twenty hours.

1

By morning’s gray dawn on April 20, thousands of armed men had congregated on Boston’s doorstep. They came as four separate armies, one from each of the New England colonies. But as they were on Massachusetts soil, the highest-ranking officer in the Bay Colony, General Artemas Ward, a forty-seven-year-old Shrewsbury farmer, businessman, and judge with two degrees from Harvard College, was in overall command. His army swelled rapidly. Men arrived all through April 20 and the days that followed, until, after a week, some sixteen thousand Yankee soldiers were present. While the rage for soldiering prevailed, Ward wisely had the men take an oath to serve for the remainder of the year. Impassioned and eager for heroics—and confronted with incredible peer pressure—most of the men signed on. A few thought better of it and went home, in many instances fearing that their farms and families would suffer during their prolonged absence. Some, however, may have suspected that the chaos all about them was an augury of miseries ahead. After all, the newborn army lacked tents, hygienic conditions were deplorable, and a thousand and one logistical details were yet to be worked out.

(Gary J. Antonetti, Ortelius Design)

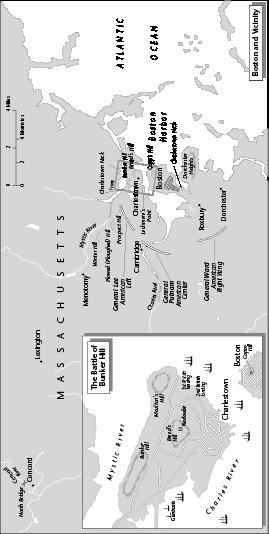

Nevertheless, after a few days Ward knew that he had an army of roughly twelve thousand men, more than double the number that Gage was thought to possess. Yet Ward never considered attacking the British. At least until the Continental Congress reconvened as scheduled on May 10, nearly three weeks in the future, Ward saw his army’s mission as one of containing the British army within Boston. New England newspapers quickly dubbed the siege army the “Grand American Army,” and General Ward just as rapidly deployed his men all along the periphery of Boston in a twelve-mile arc that stretched from east of the Mystic River to the north to Roxbury and Dorchester to the south of the city.

2

Those who had been chosen to sit in the Second Congress were preparing to leave for Philadelphia, and their responses to the outbreak of hostilities differed wildly. Galloway, though reelected, had decided to resign his seat and quit the Pennsylvania assembly as well. He did not wish to be part of any government that was at war with the mother country. Galloway also feared for his safety. It was bad enough to be regarded as an “apostate” by the other congressmen, but he was badly unnerved when someone sent a box to his home containing a noose and a note asking that he kill himself and “rid the World of a Damned Scoundrel.”

3

New York’s Robert R. Livingston, who was every bit as conservative as Galloway, was elected to Congress on the day before word of the Lexington and Concord battles reached Manhattan. Friends urged him not to attend the Congress, but he refused to listen. “My property is here [and] I cannot remove it,” he told them. “I am resolved to stand or fall with my country.”

4

John Dickinson, who charged London with having started an “impious War of Tyranny against Innocence,” was eager to be part of this congress.

5

So too was Richard Henry Lee, who raged that General Gage had launched “a wanton and cruel Attack on unarmed people … brutally [killing] Old Men, Women, & Children.”

6

John Adams declared that Britain’s use of force had “changed the Instruments of Warfare from the Penn to the Sword.” He laid aside his quill, mercifully bringing to an end his Novanglus essays, and hurried to Lexington, wishing to speak with witnesses to the incident on Lexington Green, as well as to residents along what was now and ever after called Battle Road. He found that his fellow colonists were ready for war. The “Die was cast, the Rubicon passed,” they told him, adding that they had fought on April 19 because “if We did not defend ourselves they would kill Us.” He saw abundant evidence of the recent engagement. Adams rode down Battle Road, still littered with the rotting corpses of horses and other residue of the bloody clash, and he spoke with civilians and militiamen, some with ghastly wounds. It was a profoundly disturbing experience. Aside from any haunting questions that might have troubled him regarding his accountability for having brought on hostilities, Adams was anxious for the well-being of his wife and four children, who lived even closer to Boston than did the inhabitants of Lexington and Concord. Would they, too, face similar horrors? Overwrought by his day at the scene of suffering, Adams fell ill that evening “with alarming Symptoms.”

7