India After Gandhi (9 page)

Read India After Gandhi Online

Authors: Ramachandra Guha

Tags: #History, #Asia, #General, #General Fiction

Jenkins did in fact ask several times for more troops and for a ‘Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron’. One reason there were too few

troops available to deal with rioters was that they were busy guarding the paranoid rulers, who were convinced that British civilians would be attacked as soon as the decision to leave was made public. This feeling was widespread among all sections of Europeans in India: among officers, priests, planters, and merchants. In the summerof1946, a young English official wrote to his family that ‘we shall virtually have the whole country against us (for long enough at all events to wipe out our scattered European population) before the show becomes, as inevitably it will, a communal scrap between Hindusand Muslims’.

16

To make the protection of British lives the top priority was pretty much state policy. In February 1947 the governor of Bengal said that his ‘first action in the event of an announcement of a date for withdrawal of British power . . . would be to have the troops “standing to” and prepare for a concentration of outlying Europeans at very short notice as soon as hostile reactions began to showthemselves’.

17

In fact, in the summer of 1947 white men and women were the safest people in India. No one was interested in killing them.

18

But their insecurity meant that many army units were placed near European settlements instead of being freed for riot control elsewhere.

The instinct of self-preservation also lay behind the decision to postpone the Punjab boundary award until after the date of Independence. On 22 July, after a visit to Lahore, Lord Mountbatten wrote to Sir Cyril Radcliffe asking himto hurry things up, for ‘every extra day’ would lessen the risk of disorder. The announcement of the boundary award

before

Independence would have allowed movements of troops to be made in advance of the transfer of power. The governor of Punjab was also very keen that the award be announced as soon as it was finalized. As it happened, Radcliffe was ready with the award on 9 August itself. However, Mountbatten now changed his mind, and chose to make the award public only after the 15th. His explanation for the delay was strange, to say the least: ‘Without question, the earlier it was published, the more the British would have to bear responsibility for the disturbances which would undoubtedly result.’ By the same token, ‘the later we postponed publication, the less would the inevitable odium react upon the British’.

19

As a rule, one must write of history only as it happened, not how it might have happened. Would amore extended time frame – an announcement in April 1947 that the British would quit in a year’s time – have allowed for a less painful process of division? Would more active

troop deployments and an earlier announcement of the Radcliffe award have led to less violence in the Punjab? Perhaps. Or perhaps not. As it turned out, the most appropriate epitaph on the last days of the Raj was provided by the Punjab official who told a young social worker from Oxford: ‘You British believe in fair play. You have left India in the same condition of chaos as you found it.’

20

While the debates continue to rage about the causes of Partition, somewhat less attention has been paid to its consequences. These were quite considerable indeed – as this book will demonstrate. The division of India was to cast a long shadow over demography, economics, culture, religion, law, international relations, and party politics.

PPLES

IN

THE

B

ASKET

The Indian States are governed by treaties . . . The Indian States, if they do not join this Union, will remain in exactly the same situation as they are today.

SIR

S

TAFFORD

C

RIPPS

, British politician, 1942

We shall have to come out in the open with [the] Princes sooner or later. We are at present being dishonest in pretending we can maintain all these small States, knowing full well in practice we shall be unable to.

IL

ORD

W

AVELL

, Viceroy of India, 1943

F

EW

MEN

HAVE

BEEN

so concerned about how history would portray them as Lord Mountbatten, the last viceroy and governor general of India. As a veteran journalist once remarked, Mountbatten appeared to act as ‘his own Public Relations Officer’.

1

An aide of Mountbatten was more blunt, calling his boss ‘the vainest man alive’. The viceroy always instructed photographers to shoot him from six inches above the eyeline because his friend, the actor Cary Grant, had told him that this way the wrinkles didn’t show. When Field Marshal Montgomery visited India, and the press clamoured for photos of the two together, Mountbatten was dismayed to find that Monty wore more medals than himself.

2

Altogether, Mountbatten had a personality that was in marked contrast to that of his predecessor, Lord Wavell. A civil servant who worked under Wavell noticed that ‘vanity, pomposity and other such weaknesses never touched him', another way of saying that he did not look to, or care about, how history would judge him.

3

Yet it is Wavell

who should get most of the credit for initiating the end of British rule in India. While sceptical of the political class, he was, despite the reserve which he displayed to them, deeply sympathetic to Indian aspirations.

4

It was he who set in motion the discussions and negotiations at the end of the war, and it was he who pressed for a clear timetable for withdrawal. But it was left to his flamboyant successor to make the last dramatic gestures that announced the birth of the two newnations.

After Mountbatten left India he worked hard to present the best possible spin on his tenure as viceroy. He commissioned or influenced a whole array of books that sought to magnify his successes and gloss his failures. These books project an impression of Mountbatten as a wise umpire successfully mediating between squabbling school boys, whether India and Pakistan, the Congress and the Muslim League, Mahatma Gandhi and M. A. Jinnah, or Jawaharlal Nehru and Vallabhbhai Patel.

5

His credit claims are taken at face value, sometimes absurdly so, as in the suggestion that Nehru would not have included Patel in his Cabinet had it not been for Mountbatten’s recommendation.

6

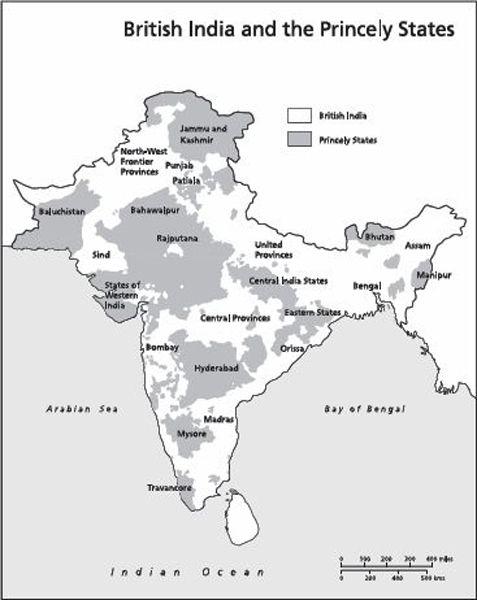

Curiously, Mountbatten’s real contribution to India and Indians has been rather underplayed by his hagiographers. This was his part in solving a geopolitical problem the like of which no newly independent state had ever faced (or is likely to face in the future). For when the British departed the subcontinent they left behind more than 500 distinct pieces of territory. Two of these were the newly created nations of India and Pakistan; the others comprised the assorted chiefdoms and states that made up what was known as ‘princely India’. The dissolution of these units is a story of extraordinary interest, told from a partisan point of view half a century ago in V. P. Menon’s

Integration of the Indian

States, but not else where or since.

7

The princely states were so many that there was even disagreement as to their number. One historian puts it at 521; another at 565. They were more than 500, by any count, and they varied very widely in terms of size and status. At one end of the scale were the massive states of Kashmir and Hyderabad, each the size of a large European country; at the other end, tiny fiefdoms or

jagirs

of a dozen or less villages.

The larger princely states were the product of the

longue durée

of

Indian history as much as of British policy. Some states made much of having resisted the waves of Muslim invaders who swept through north India between the eleventh and sixteenth centuries. Others owed their very history to association with these invaders, as for instance the Asaf Jah dynasty of Hyderabad, which began life in the early eighteenth century as a vassal state of the great Mughal Empire. Yet other states, such as Cooch Behar in the east and Garhwal in the Himalayan north, were scarcely touched by Islamic influence at all.

Whatever their past history, these states owed their mid-twentieth-century shape and powers – or lack thereof – to the British. Starting as a firm of traders, the East India Company gradually moved towards a position of overlordship. They were helped here by the decline of the Mughals after the death of Aurangzeb in 1707. Indian rulers were seen by the Company as strategic allies, useful in checking the ambitions of their common enemy, the French. The Company forced treaties on these states, which recognized it as the ‘paramount power’. Thus, while legally the territories the various Nawabs and Maharajas ruled over were their own, the British retained to themselves the right to appoint ministers and control succession, and to extract a large subsidy for the provision of administrative and military support. In many cases the treaties also transferred valuable areas from the Indian states to the British. It was no accident that, except for the states comprising Kathia-war and two chiefdoms in the south, no Indian state had a coastline. The political dependence was made more acute by economic dependence, with the states relying on British India for raw materials, industrial goods, and employment opportunities.

8

The larger native states had their own railway, currency and stamps, vanities allowed them by the Crown. Few had any modern industry; fewer still modern forms of education. A British observer wrote in the early twentieth century that, taken as a whole, the states were ‘sinks of reaction and incompetence and unrestrained autocratic power sometimes exercised by vicious and deranged individuals’.

9

This, roughly, was also the view of the main nationalist party, the Congress. From the 1920s they pressed the state rulers to at least match the British in allowing a modicum of political representation. Under the Congress umbrella rested the All-India States Peoples Conference, to which in turn were affiliated the individual

praja mandals

(or peoples’ societies) of the states.

Even in their heyday the princes got a bad press. They were generally viewed as feckless and dissolute, over-fond of racehorses and

other men’s wives and holidays in Europe. Both the Congress and the Raj thought that they cared too little for mundane matters of administration. This was mostly true, but there were exceptions. The maharajas of Mysore and Baroda both endowed fine universities, worked against caste prejudice and promoted modern enterprises. Other maharajas kept going the great traditions of Indian classical music.

Good or bad, profligate or caring, autocratic or part-democratic, by the 1940s all the princes now found themselves facing a common problem: their future in a free India. In the first part of 1946 British India had a definitive series of elections, but these left untouched the princely states. As a consequence there was a ‘growing antipathy towards princely governments’.

10

Their constitutional status, however, remained ambiguous. The Cabinet Mission of 1946 focused on the Hindu–Muslim or United India versus Pakistan question; it barely spoke of the states at all. Likewise the statement of 20 February 1947, formally announcing that the Raj was to end, also finessed the question. On 3 June the British announced both the date of their final withdrawal and the creation of two dominions – but this statement also did not make clear the position of the states. Some rulers began now ‘to luxuriate in wild dreams of independent power in an India of many partitions’.

11

Now, just in time, came the wake-up calls.

In 1946–7 the president of the All-India States Peoples Conference was Jawaharlal Nehru. His biographer notes that Nehru ‘held strong views on this subject of the States. He detested the feudal autocracy and total suppression of popular feeling, and the prospect of these puppet princes . . . setting themselves up as independent monarchs drove him into intense exasperation.’

12

The prospect was encouraged by the officials of the Political Department, who led the princes to believe that once the British had left they could, if they so wished, stake their claims to independence.