Infinite Dreams (3 page)

Authors: Joe Haldeman

Yet I thought I was onto something. Most aliens in science fiction aren’t truly alien, and that’s not because science

fiction writers lack imagination, but because the purpose of an alien in a story is usually to provide a meaningful distortion of human nature. My purpose was not nearly so elevated; my aliens were there as unwitting vehicles for absurdist humor. All the story needed was a couple of bewildered humans, to serve as foils for alien nature. Once I saw that, the story practically wrote itself.

In the process of writing itself, the story generated two dreadful puns. I’m not responsible.

His name is Three-phasing and he is bald and wrinkled, slightly over one meter tall, large-eyed, toothless and all bones and skin, sagging pale skin shot through with traceries of delicate blue and red. He is considered very beautiful but most of his beauty is in his hands and is due to his extreme youth. He is over two hundred years old and is learning how to talk. He has become reasonably fluent in sixty-three languages, all dead ones, and has only ten to go.

The book he is reading is a facsimile of an early edition of Goethe’s

Faust

. The nervous angular Fraktur letters goose-step across pages of paper-thin platinum.

The

Faust

had been printed electrolytically and, with several thousand similarly worthwhile books, sealed in an argon-filled chamber and carefully lost, in 2012 A.D.; a very wealthy man’s legacy to the distant future.

In 2012 A.D., Polaris had been the pole star. Men eventually got to Polaris and built a small city on a frosty planet there. By that time, they weren’t dating by prophets’ births any more, but it would have been around 4900 A.D. The pole star by then, because of precession of the equinoxes, was a dim thing once called Gamma Cephei. The celestial pole kept reeling around, past Deneb and Vega

and through barren patches of sky around Hercules and Draco; a patient clock but not the slowest one of use, and when it came back to the region of Polaris, then 26,000 years had passed and men had come back from the stars, to stay, and the book-filled chamber had shifted 130 meters on the floor of the Pacific, had rolled into a shallow trench, and eventually was buried in an underwater landslide.

The thirty-seventh time this slow clock ticked, men had moved the Pacific, not because they had to, and had found the chamber, opened it up, identified the books and carefully sealed them up again. Some things by then were more important to men than the accumulation of knowledge: in half of one more circle of the poles would come the millionth anniversary of the written word. They could wait a few millenia.

As the anniversary, as nearly as they could reckon it, approached, they caused to be born two individuals: Nine-hover (nominally female) and Three-phasing (nominally male). Three-phasing was born to learn how to read and speak. He was the first human being to study these skills in more than a quarter of a million years.

Three-phasing has read the first half of

Faust

forwards and, for amusement and exercise, is reading the second half backwards. He is singing as he reads, lisping.

“Fain’ Looee w’mun … wif all’r die-mun ringf …” He has not put in his teeth because they make his gums hurt.

Because he is a child of two hundred, he is polite when his father interrupts his reading and singing. His father’s “voice” is an arrangement of logic and aesthetic that appears in Three-phasing’s mind. The flavor is lost by translating into words:

“Three-phasing my son-ly atavism of tooth and vocal cord,” sarcastically in the reverent mode, “Couldst tear thyself

from objects of manifest symbol, and visit to share/help/learn, me?”

“?” He responds, meaning “with/with/of what?”

Withholding mode: “Concerning thee: past, future.”

He shuts the book without marking his place. It would never occur to him to mark his place, since he remembers perfectly the page he stops on, as well as every word preceding, as well as every event, no matter how trivial, that he has observed from the precise age of one year. In this respect, at least, he is normal.

He thinks the proper coordinates as he steps over the mover-transom, through a microsecond of black, and onto his father’s mover-transom, about four thousand kilometers away on a straight line through the crust and mantle of the earth.

Ritual mode: “As ever, father.” The symbol he uses for “father” is purposefully wrong, chiding. Crude biological connotation.

His father looks cadaverous and has in fact been dead twice. In the infant’s small-talk mode he asks “From crude babblings of what sort have I torn your interest?”

“The tale called

Faust

, of a man so named, never satisfied with {symbol for slow but continuous accretion} of his knowledge and power; written in the language of Prussia.”

“Also depended-ing on this strange word of immediacy, your Prussian language?”

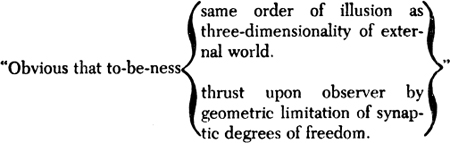

“As most, yes. The word of ‘to be’:

sein

. Very important illusion in this and related languages/cultures; that events happen at the ‘time’ of perception, infinitesimal midpoint between past and future.”

“Convenient illusion but retarding.”

“As we discussed 129 years ago, yes.” Three-phasing is impatient to get back to his reading, but adds:

“You always stick up for them.”

“I have great regard for what they accomplished with limited faculties and so short lives.” Stop beatin’ around the bush, Dad.

Tempis fugit

, eight to the bar. Did Mr. Handy Moves-dat-man-around-by-her-apron-strings, 20th-century American poet, intend cultural translation of

Lysistrata?

if so, inept. African were-beast legendry, yes.

Withholding mode (coy): “Your father stood with Nine-hover all morning.”

“,” broadcasts Three-phasing: well?

“The machine functions, perhaps inadequately.”

The young polyglot tries to radiate calm patience.

“Details I perceive you want; the idea yet excites you. You can never have satisfaction with your knowledge, either. What happened-s to the man in your Prussian book?”

“He lived-s one hundred years and died-s knowing that a man can never achieve true happiness, despite the appearance of success.”

“For an infant, a reasonable perception.”

Respectful chiding mode: “One hundred years makes-ed Faust a very old man, for a Dawn man.”

“As I stand,” same mode, less respect, “yet an infant.” They trade silent symbols of laughter.

After a polite tenth-second interval, Three-phasing uses the light interrogation mode: “The machine of Nine-hover …?”

“It begins to work but so far not perfectly.” This is not news.

Mild impatience: “As before, then, it brings back only rocks and earth and water and plants?”

“Negative, beloved atavism.” Offhand: “This morning she caught two animals that look as man may once have looked.”

“!” Strong impatience, “I go?”

“.” His father ends the conversation just two seconds after it began.

Three-phasing stops off to pick up his teeth, then goes directly to Nine-hover.

A quick exchange of greeting-symbols and Nine-hover presents her prizes. “Thinking I have two different species,” she stands: uncertainty, query.

Three-phasing is amused. “Negative, time-caster. The male and female took very dissimilar forms in the Dawn times.” He touches one of them. “The round organs, here, served-ing to feed infants, in the female.”

The female screams.

“She manipulates spoken symbols now,” observes Nine-hover.

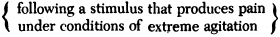

Before the woman has finished her startled yelp, Three-phasing explains: “Not manipulating concrete symbols; rather, she communicates in a way called ‘non-verbal,’ the use of such communication predating even speech.” Slipping into the pedantic mode: “My reading indicates that such a loud noise occurs either since she seems not in pain, then she must fear me or you or both of us.

since she seems not in pain, then she must fear me or you or both of us.

“Or the machine,” Nine-hover adds.

Symbol for continuing. “We have no symbol for it but in Dawn days most humans observed ‘xenophobia,’ reacting

to the strange with fear instead of delight. We stand as strange to them as they do to us, thus they register fear. In their era this attitude encouraged-s survival.

“Our silence must seem strange to them, as well as our appearance and the speed with which we move. I will attempt to speak to them, so they will know they need not fear us.”

Bob and Sarah Graham were having a desperately good time. It was September of 1951 and the papers were full of news about the brilliant landing of U.S. Marines at Inchon. Bob was a Marine private with two days left of the thirty days’ leave they had given him, between boot camp and disembarkation for Korea. Sarah had been Mrs. Graham for three weeks.

Sarah poured some more bourbon into her Coke. She wiped the sand off her thumb and stoppered the Coke bottle, then shook it gently. “What if you just don’t show up?” she said softly.

Bob was staring out over the ocean and part of what Sarah said was lost in the crash of breakers rolling in. “What if I what?”

“Don’t show up.” She took a swig and offered the bottle. “Just stay here with me. With us.” Sarah was sure she was pregnant. It was too early to tell, of course; her calendar was off but there could be other reasons.

He gave the Coke back to her and sipped directly from the bourbon bottle. “I suppose they’d go on without me. And I’d still be in jail when they came back.”

“Not if—”

“Honey, don’t even talk like that. It’s a just cause.”

She picked up a small shell and threw it toward the water.

“Besides, you read the

Examiner

yesterday.”

“I’m cold. Let’s go up.” She stood and stretched and delicately brushed sand away. Bob admired her long naked dancer’s body. He shook out the blanket and draped it over her shoulders.

“It’ll all be over by the time I get there. We’ll push those bastards—”

“Let’s not talk about Korea. Let’s not talk.”

He put his arm around her and they started walking back toward the cabin. Halfway there, she stopped and enfolded the blanket around both of them, drawing him toward her. He always closed his eyes when they kissed, but she always kept hers open. She saw it: the air turning luminous, the seascape fading to be replaced by bare metal walls. The sand turns hard under her feet.

At her sharp intake of breath, Bob opens his eyes. He sees a grotesque dwarf, eyes and skull too large, body small and wrinkled. They stare at one another for a fraction of a second. Then the dwarf spins around and speeds across the room to what looks like a black square painted on the floor. When he gets there, he disappears.

“What the hell?” Bob says in a hoarse whisper.

Sarah turns around just a bit too late to catch a glimpse of Three-phasing’s father. She does see Nine-hover before Bob does. The nominally-female time-caster is a flurry of movement, sitting at the console of her time net, clicking switches and adjusting various dials. All of the motions are unnecessary, as is the console. It was built at Three-phasing’s suggestion, since humans from the era into which they could cast would feel more comfortable in the presence of a machine that looked like a machine. The actual time net was roughly the size and shape of an asparagus stalk, was controlled completely by thought, and had no

moving parts. It does not exist any more, but can still be used, once understood. Nine-hover has been trained from birth for this special understanding.

Sarah nudges Bob and points to Nine-hover. She can’t find her voice; Bob stares open-mouthed.

In a few seconds, Three-phasing appears. He looks at Nine-hover for a moment, then scurries over to the Dawn couple and reaches up to touch Sarah on the left nipple. His body temperature is considerably higher than hers, and the unexpected warm moistness, as much as the suddenness of the motion, makes her jump back and squeal.

Three-phasing correctly classified both Dawn people as Caucasian, and so assumes that they speak some Indo-European language.

“GutenTagsprechensieDeutsch?”

he says in a rapid soprano.

“Huh?” Bob says.

“Guten-Tag-sprechen-sie-Deutsch?”

Three-phasing clears his throat and drops his voice down to the alto he uses to sing about the St. Louis woman. “

Guten Tag

,” he says, counting to a hundred between each word. “

Sprechen sie Deutsch?”