Infinite Dreams (30 page)

Authors: Joe Haldeman

Ideas are cheap, even crazy ones. Every writer has had the experience of a friend or relative—or stranger!—saying, “I’ve got this great idea for a story.. you write it and I’ll split the money with you fifty-fifty.” The proper response to this depends on the generous person’s occupation. In the case of a prizefighter, for instance, you might offer to name a few potential opponents, and only demand half the purse. An editor, of course, you humor. They rarely ask for as much as half.

All of this is not to say that there aren’t days when you sit down at the typewriter and find that your imagination has frozen solid; you can’t come up with anything to write, no ideas come floating down out of Lafferty’s ether. When

this happens in the middle of a novel, it’s a scary thing. But if you’re just feeing a short story that won’t get itself started, there’s an easy way to cope with it, a trade secret that Gordon R. Dickson passed on to me, saying it hadn’t foiled him in twenty years:

Start typing. Type your name over and over. Type lists of animals, flowers, baseball players, Greek Methodists. Type out what you’re going to say to that damned insolent repairman. Sooner or later, perhaps out of boredom, perhaps out of a desire to

stop

this silly exercise, you’ll find you’ve started a story. It’s never taken me so much as a page of nonsense, and the stories started this way aren’t any worse than the one about the artichoke.

One restriction most good science fiction writers accept without question is that the scientific content of their stories be as accurate as possible. Is this really necessary? Yes, but not for the obvious didactic reason. We are not obligated (or qualified, in most cases) to

teach

science to anybody.

A person who thinks he learns science from science fiction is like one who thinks he learns history from historical novels, and he deserves what he gets. Some few science fiction writers, like Gregory Benford and Philip Latham, are working scientists, and a good fraction of the rest of us have degrees in some science. That doesn’t make us qualified to write with authority on subjects outside of our areas of study—but we do it; you’d have a short career if all of your stories were about magnetohydrodynamics or galactic morphology. So we try to be intelligent laymen in other fields, staying current enough so that our inevitable errors won’t be obvious to other laymen.

Any fiction writer is in the business of maintaining illusion.

Like a stage magician, his authority lasts only until he makes his first error.

*

Every writer has to deal with mechanical consistencies like making sure the woman named Marie in chapter one doesn’t turn into Mary in chapter four. He also has to be careful about routine details, not letting the sun set in the east (as John Wayne made it do in

The Green Berets

), and so forth. If he writes in a genre, he has an added burden of detail, since most of his readers consider themselves experts. Mundane esoterica: Spies call the CIA the Company, not the Agency. A private eye doesn’t have to break into a car and read the registration card to find out who own it; he jots down the license number and sends a form to the Department of Motor Vehicles. A cowboy normally carried only five shots in his six-shooter; only a fool would leave the hammer down on a live round.

One reason science fiction is harder to write than other forms of genre fiction is that this universe of detail is larger, more difficult of access, and constantly changing. I wonder how many novels-in-progress got thrown across the room in 1965, when scientists found that Mercury

didn’t

keep one face always to the Sun, after all. I wonder how many bad ones got finished anyhow.

Nobody can be an expert on everything from ablation physics to zymurgy, so you have to work from a principle of exclusion: know the limits of your knowledge and never expose your ignorance by attempting to write with authority

when you don’t really know what’s going on. This advice is easier to give than to take. I’ve been caught in basic mistakes in genetics, laser technology, and even metric nomenclature—in the first printing of

The Forever War

I referred time and again to a unit of power called the “beva-watt.” What I

meant

was

“gigawatt”;

the only thing

“bev”

means is billion-electron-volt, a unit of energy, not power. I got letters. Boy, did I get letters.

The letters are humbling, and time-consuming if you feel obligated to answer them (I do, so long as they aren’t abusive or idiotic). But the possibility of being caught in error isn’t the main reason for taking pains.

When I finish writing a science fiction novel I have a notebook or two of technical notes, equations, diagrams, graphs. Even a short story, if it’s a hard-core-science one like “Tricentennial,” might generate a dozen pages of notes. Not one percent of this stuff finds its way into the story. It may even be naive science and weak mathematics—but it will have served its purpose if it has made a fictional world solid and real to me.

Because this business of illusion works both ways. For a story to succeed, the writer must himself be convinced that the background and situation the story is built on make sense. Ernest Hemingway pointed out (though I think Gertrude Stein said it first) that the prose of a story should move with the steady grace of an iceberg, and for the same reason an iceberg does: seven-eighths of it is beneath the surface. The author must know much more than the reader sees. And he must believe, at least for the duration.

Which brings us back to Mr. Lafferty. What I’m really doing with all these equations and graphs, I think, is putting myself into a properly receptive frame of mind. Other writers draft endless outlines to the same purpose, or sharpen pencils down to useless stubs, or take meditative walks,

or drink bourbon. And through some mystical—or subconscious, or subrational—process, where there was white paper there’s a sentence, a page, a story. Finding the proper words is not at all a mystical process, just creative labor. The ideas that serve as scaffolding for the words, though—they come from out of nowhere, and serve you, then return.

—Joe Haldeman

Florida

, 1978

*

You may note that these add up to more than the total number of stories. I can’t balance my checkbook, either.

*

An editor of recent memory, who came to science fiction from the editing of wrestling magazines, and has since gone on to even greater things, once petitioned a number of writers for “an anti-homosexuality science fiction story.” None was quite that desperate for work.

*

I saw an act in Las Vegas where the magician exploited this sentiment by deliberately introducing mistakes, which grew more and more outrageous until his act degenerated into slapstick, and it was more entertaining than any straight sleight-of-hand. Good surreal writers like Brautigan, Disch, and Garcia Marquez also succeed by deliberately manipulating the consensus of illusion we call reality, but that’s not the kettle of fish we’re discussing here.

Joe Haldeman is a renowned American science fiction author whose works are heavily influenced by his experiences serving in the Vietnam War and his subsequent readjustment to civilian life.

Haldeman was born on June 9, 1943, to Jack and Lorena Haldeman. His older brother was author Jack C. Haldeman II. Though born in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma, Haldeman spent most of his youth in Anchorage, Alaska, and Bethesda, Maryland. He had a contented childhood, with a caring but distant father and a mother who devoted all her time and energy to both sons.

As a child, Haldeman was what might now be called a geek, happy at home with a pile of books and a jug of lemonade, earning money by telling stories and doing science experiments for the neighborhood kids. By the time he entered his teens, he had worked his way through numerous college books on chemistry and astronomy and had skimmed through the entire encyclopedia. He also owned a small reflecting telescope and spent most clear nights studying the stars and planets.

Fascinated by space, the young Haldeman wanted to be a “spaceman”—the term

astronaut

had not yet been coined—and carried this passion with him to the University of Maryland, from which he graduated in 1967 with a bachelor of science degree in physics and astronomy. By this time the United States was in the middle of the Vietnam War, and Haldeman was immediately drafted.

He spent one year in Vietnam as a combat engineer and earned a Purple Heart for severe wounds. Upon his return to the United States in 1969, during the thirty-day “compassionate leave” given to returning soldiers, Haldeman typed up his first two stories, written during a creative writing class in his last year of college, and sent them out to magazines. They both sold within weeks, and the second story was eventually adapted for an episode of

The Twilight Zone

. At this point, though, Haldeman was accepted into a graduate program in computer science at the University of Maryland. He spent one semester in school. He was also invited to attend the Milford Science Fiction Writers’ Conference—a rare honor for a novice writer.

In September of the same year, Haldeman wrote an outline and two chapters of

War Year

, a novel that would be based on the letters he had sent to his wife, Gay, from Vietnam. Two weeks later he had a major publishing contract. Mathematics was out of the picture for the near future.

Haldeman enrolled in the University of Iowa Writers’ Workshop, where he studied with luminary figures such as Vance Bourjaily, Raymond Carver, and Stanley Elkin, graduating in 1975 with a master of fine arts degree in creative writing. His most famous novel,

The Forever War

(1974), began as his MFA thesis and won him his first Hugo and Nebula Awards, as well as the Locus and Ditmar Awards.

Haldeman was now at his most productive, working on several projects at once. Arguably his largest-scale undertaking was the Worlds trilogy, consisting of

Worlds

(1981),

Worlds Apart

(1983), and

Worlds Enough and Time

(1992). Immediately before releasing the series’ last installment, however, Haldeman published his renowned novel

The Hemingway Hoax

(1990), which dealt with the experiences of combat soldiers in Vietnam. The novella version of the book won both the Hugo and Nebula Awards, a feat that Haldeman repeated with the publication of his next novel,

Forever Peace

(1997), which also won the John W. Campbell Memorial Award for Best Science Fiction Novel.

In 1983 Haldeman accepted an adjunct professorship in the writing program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He taught every fall semester, preferring to be a full-time writer for the remainder of the year. While at MIT he wrote

Forever Free

, the final book in his now-famous Forever War trilogy.

Haldeman has since written or edited more than a half-dozen books, with a second succession of titles being published in the early 2000s, including

The Coming

(2000),

Guardian

(2002),

Camouflage

(2004)—for which he won his fourth Nebula—and

The Old Twentieth

(2005). He also released the Marsbound trilogy, publishing the namesake title in 2008 and quickly following it with

Starbound

(2010) and

Earthbound

(2011).

A lifetime member and past president of the Science Fiction Writers of America, Haldeman was selected as its Damon Knight Memorial Grand Master for 2010. He was inducted into the Science Fiction Hall of Fame in 2012.

After publishing his novel

Work Done for Hire

and retiring from MIT in 2014, Haldeman now lives in Gainesville, Florida, and plans to continue writing a novel every couple of years.

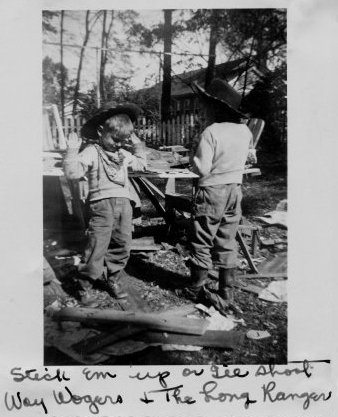

The author and his brother, Jack, around the year 1948. The image is captioned “Stick ’em up or I’ll shoot. Woy Wogers and the Long Ranger.”

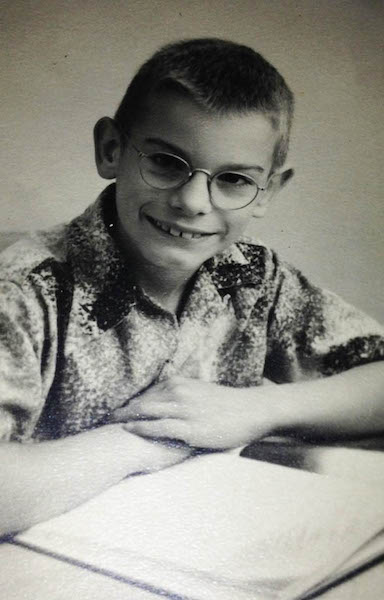

Haldeman in third grade, the year he discovered science fiction.