infinities (7 page)

Authors: John Grant,Eric Brown,Anna Tambour,Garry Kilworth,Kaitlin Queen,Iain Rowan,Linda Nagata,Kristine Kathryn Rusch,Scott Nicholson,Keith Brooke

She had looked at me with that cool, assessing gaze of hers, and said, "Well, I'm proud of you."

Now I ate my salad sandwich and fielded her questions about my next serious novel.

How could I tell her that, for the time being, I had shelved plans for the next book, the yearly novel that would appear under my own name? The last one had sold poorly; my editor had refused to offer an advance for another. My agent had found some hackwork to tide me over, and I had put off thinking about the next Daniel Ellis novel.

I changed the subject, asked her about her sister, Liz, and for the next fifteen minutes lost myself in contemplation of her face: square, large-eyed, attractive in that worn, mid-thirties way that signals experience with fine lines about the eyes. The face of the woman I loved.

We left the tea-room and ambled through the cobbled streets towards the Minster. She took my arm, smiling at the Christmas window displays on either hand.

Then she stopped and tugged at me. "Daniel, look. I don't recall..."

It was a second-hand bookshop crammed into the interstice between a gift shop and an establishment selling a thousand types of tea. The lighted window displayed a promising selection of old first editions. Mina was already dragging me inside.

The interior of the premises opened up like an optical illusion, belying the parsimonious dimensions of its frontage. It diminished in perspective like a tunnel, and narrow wooden stairs gave access to further floors.

Mina was soon chatting to the proprietor, an owl-faced, bespectacled man in his seventies. "We moved in just last week," he was saying. "Had a place beyond the Minster—too quiet. You're looking for the Victorians? You'll find them in the first room on the second floor."

I followed her up the precipitous staircase, itself made even narrower by shelves of books on everything from angling to bee-keeping, gardening to rambling.

Mina laughed to herself on entering the well-stocked room and turned to me with the conspiratorial grin of the fellow bibliophile. While she lost herself in awed contemplation of the treasures in stock, I saw a sign above a door leading to a second room: Twentieth Century Fiction.

I stepped through, as excited as a boy given the run of a toyshop on Christmas Eve.

The room was packed from floor to ceiling with several thousand volumes. At a glance I knew that many dated from the thirties and forties: the tell-tale blanched pink spines of Hutchinson editions, the pen and ink illustrated dust-jackets so popular at the time. The room had about it an air of neglect, the junk room where musty volumes were put out to pasture before the ultimate indignity of the council skip.

I found a Robert Nathan for one pound, a Wellard I did not posses for £1.50. I remembered Vaughan Edwards, and moved with anticipation to the E section. There were plenty of Es, but no Edwards.

I moved on, disappointed, but still excited by the possibility of more treasures to be found. I was scanning the shelves for Rupert Croft-Cooke when Mina called out from the next room, "Daniel. Here."

She had a stack of thick volumes piled beside her on the bare floorboards, and was holding out a book to me. "Look."

I expected some title she had been looking out for, but the book was certainly not Victorian. It had the modern, maroon boards of something published in the fifties.

"Isn't he the writer you mentioned the other week?"

I read the spine.

A Bitter Recollection

—Vaughan Edwards.

I opened the book, taking in the publishing details, the full-masted galleon symbol of the publisher, Longmans, Green and Company. It was his fourth novel, published in 1958.

I read the opening paragraph, and something clicked. I knew I had stumbled across a like soul.

An overnight frost had sealed the ploughed fields like so much stiffened corduroy, and in the distance, mist shrouded and remote, stood the village of Low Dearing. William Barnes, stepping from the second-class carriage onto the empty platform, knew at once that this was the place

.

"Where did you find it?" I asked, hoping that there might be others by the author.

She laughed. "Where do you think? Where it belongs, on the 50p shelf."

She indicated a free-standing bookcase crammed with a miscellaneous selection of oddments, warped hardbacks, torn paperbacks, pamphlets and knitting patterns. There were no other books by Vaughan Edwards.

I lay my books upon her pile on the floor and took Mina in my arms. She stiffened, looking around to ensure we were quite alone: for whatever reasons, she found it difficult to show affection when we might be observed.

We made our way carefully down the stairs and paid for our purchases. I indicated the Edwards and asked the proprietor if he had any others by the same author.

He took the book and squinted at the spine. "Sorry, but if you'd like to leave your name and address..."

I did so, knowing that it would come to nothing.

We left the shop and walked back to the car, hand in hand. We drove back through the rapidly falling winter twilight, the traffic sparse on the already frost-scintillating B-roads. The gritters would be out tonight, and the thought of the cold spell gripping the land filled me with gratitude that soon I would be home, before the fire, with my purchases.

For no apparent reason, Mina lay a hand on my leg as I drove, and closed her eyes.

I appreciated her spontaneous displays of affection all the more because they were so rare and arbitrary. Sometimes the touch of her hand in mine, when she had taken it without being prompted, was like a jolt of electricity.

The moon was full, shedding a magnesium light across the fields around the cottage. As I was about to turn into the drive, the thrilling, bush-tailed shape of a fox slid across the metalled road before the car, stopped briefly to stare into the headlights, then flowed off again and disappeared into the hedge.

...continues

Copyright information

© Eric Brown 2001, 2011

A Writer's Life

was first published by PS Publishing in 2001, and is reprinted in ebook format by infinity plus:Buy now:

A Writer's Life by Eric Brown

$2.99 / £2.23.

Qinmeartha and the Girl-Child LoChi

Tarburton-on-the-Moor – just another sleepy Dartmoor village. Or so it seems to Joanna Gard when she comes to visit her elderly aunt here, until the fabric of the village begins, like her personal life, to unravel. The villagers become less and less substantial as she watches, the local church degenerates into a nexus of terrifying malevolence, siblings of a horrifyingly seductive family pull her inexorably towards them, elementals play with her terrors on the midnight moor ... At last Joanna is compelled to realize that a duel of wills between eternal forces is being played out – that nothing, herself included, is what it seems to be.

In this uncomfortably disturbing tale of clashing realities, Hugo- and World Fantasy Award-winning author John Grant skilfully juggles a strange, fantasticated cosmology with images from the darker side of the human soul.

Includes bonus novella "The Beach of the Drowned".

Buy now:

Qinmeartha and the Girl-Child LoChi by John Grant

$2.99 / £2.18.

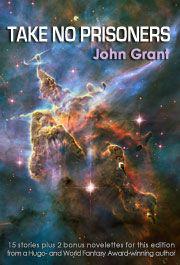

In the fifteen superbly literary stories of this, his first collection, Hugo- and World Fantasy Award-winning author John Grant goes to places other fantasy and SF writers have yet to find on the map. As a special bonus, this new e-edition of

Take No Prisoners

includes two novelettes from the author's Leaving Fortusa cycle: "The Hard Stuff" and "Q".

Buy now:

Take No Prisoners by John Grant

$2.99 / £2.23.

'Grant's hate for the war and the warmongers almost sets the pages on fire, but the love he portrays is just as powerful.' —

Lois Tilton

,

Tangent

, on 'The Hard Stuff'

'There is more than enough hatred for the George W. Bush administration to go round and John Grant's 'Q' is not the only story to fuel itself on this anger. It might well be the best, though.' —

Martin Lewis

,

The Ellen Datlow/SCIFICTION Project

, on 'Q'

'I am struck here not only by the variety of these stories, and the impressive imagination, but by the control of voice. This is a book of first-rate work, by a writer worthy of more of our attention.' —

Rich Horton

,

Locus

'Do not open this book until you are prepared to dive in and forget the day. The worlds of John Grant are harsh, interconnected, florid, fluent, fun; and, more than all of that, they are generous. His tales are long and full. And his characters live at full stretch, because John Grant gives each of them his own contentious, passionate, loving heart. Read and weep, read and laugh; but don't begin to read until you're ready for a long joy.' —

John Clute

'John Grant is a master of transcendent literary fantasy, and one of my idols. His work is baroque, rich, often blurring the fine borders between symbol and reality, science and faith, philosophy and dogma, imagination and probability. With effortless skill he pours it all into a spicy cauldron of story, stirs it up with a biting-hot ladle of words, and the delicious result is Take No Prisoners.' —

Vera Nazarian

It was while I was studying for my doctorate in veterinary science that I first developed that passion for the cinema which came to dominate my later career, at the expense, alas, of all the dogs and cats and cows and horses I might have treated had my life gone according to the original plan. It's silly to wish one could change the past, of course, but sometimes I catch myself thinking that each of us should be given more than one life – not sequentially, but in parallel, so we could pursue several lifelines simultaneously. I would like to have been a vet

as well as

an expert on the movies, the author of over twenty critical studies, a reference work that I revise annually, and more articles and reviews than I could possibly have the time to count. But then the director calls for silence and I start speaking into the television camera, presenting some movie or another, or discussing the latest releases, and my fancy dies because I haven't the time to continue giving it life.

I wasn't born a movie fan. As I say, I was in my mid-twenties and studying for a doctorate when circumstances conspired to germinate an interest that I suppose, on reflection, must have been latent somewhere inside of me from the outset.

Those circumstances were not particularly glamorous. Mine isn't a tale of some mentor taking me under his wing and engendering in me a deep love of the silver screen. The main factors were: shortage of money; the rule that the laboratories and library were reserved exclusively for undergraduates on Monday afternoons; and the Rupolo Cinema on Broad Street.

They don't make movie theaters like the Rupolo any more. Nowadays, aside from the fringe cinemas you can find in the bigger cities that show either experimental movies of stupefying opacity or porn, or the latter masquerading as the former, just about all the movie theaters in the country are multi-screen links of this major chain or that one, all showing only the most blatantly commercial of the new releases. But in the days when I was a footloose postgraduate, forever counting my coins to make sure I could both eat and pay the rent, you could find little cinemas like the Rupolo in small towns all over America. Sure, they carried the new movies, but generally about three months behind – an interesting temporal dislocation because, by the time a movie came to a cinema near

you

, you tended to have forgotten all the television hype there'd been around the time of original release and, often enough, to be able to recall even the title only dimly. As well as these new/oldish movies, cinemas like the Rupolo took it upon themselves to show special items, to have matinees for the kids on a Saturday morning, to run occasional "seasons" devoted to one theme or another ... It was a golden era for public appreciation of the movies, thanks to those small and generally run-down cinemas, and we didn't fully realize it until it was – and they were – gone.