Ink (2 page)

“Betsu ni,”

he said in a velvet voice.

Nothing special.

You’re lying,

I thought.

Why are you lying?

But Myu looked like she’d been punched in the gut. And even with the cultural barriers that stood in my way, it was clear to me that he’d just discounted all her suffering, her feelings—the whole relationship. He looked like he didn’t give a shit, and that’s pretty much what he’d said.

Myu’s face turned a deep crimson, and her black hair clung to the sides of her snot-streaked face. Her hands squeezed into fists at her sides. Her gaze of hope turned cold and listless, like a mirror of Yuu’s face.

And then Myu lifted her hand and slugged him right in the jaw. She hit him so hard his face twisted to the left.

He lifted his hand to rub his cheek, and as he raised his eyes, they locked with mine.

Shit.

His gaze burned into me and I couldn’t move. Heat flooded my cheeks, and shame tingled down my neck.

I couldn’t look away. I stared at him with my mouth open.

But he didn’t call me out. He lifted his head, flicked his gaze back to Myu and pretended I didn’t exist. I let out a shaky breath.

“Saitei,”

she spat, and I heard footsteps. After a moment, the door to the hallway slid shut.

I let out a breath.

Well, that was today’s dose of awkward.

I looked down at the paper, still touching the tip of my shoe. I reached for it, flipping the page over to look.

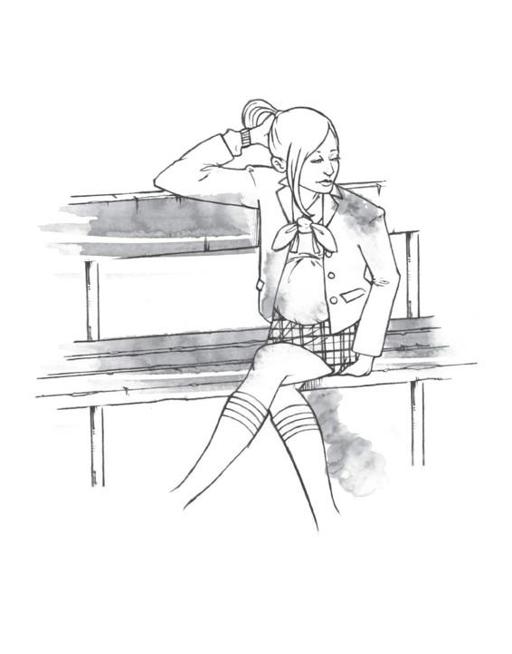

A girl lay back on a bench, roughly sketched in scrawls of ink as she looked out over the moat of Sunpu Park. She wore a school uniform, a tartan skirt clinging to her crossed legs. Little tufts of grass and flowers tangled with the bench legs, which had to be creative license—it was still too cold for blooms.

The girl was beautiful, in her crudely outlined way, with a lick of hair stuck to the back of her neck, her elbow resting against the top of the bench and her hand behind her head.

She looked out at the moat of Sunpu Park, the sunlight sparkling off the dark water.

A pregnant bump of stomach curved under her blouse.

The other girl.

A queasy feeling started to twist in my stomach, like motion sickness.

And then the sketched girl on the bench turned her head, and her inky eyes glared straight into mine.

A chill shuddered through me.

Oh my god. She’s looking at me.

A hand snatched the paper out of mine. I looked up, my mind reeling, straight into the face of Yuu Tomohiro.

He slammed the page facedown on top of the pile of drawings he’d collected. He stood too close, so that he hovered over me.

“Did you draw that?” I whispered in English. He didn’t answer, staring hard at me. His cheek burned red and puffy where Myu had hit him.

I stared back. “Did you draw it?”

He smirked.

“Kankenai darou!”

I looked at him blankly, and he sneered.

“Don’t you speak Japanese?” he said. I felt my cheeks flush with shame. He looked like he’d settled some sort of battle in his mind, and he turned, walking slowly away.

“She moved,” I blurted out.

He stumbled, just a little, but kept walking.

But I saw him stumble. And I saw the drawing look at me.

Didn’t I? My stomach churned. That was impossible, wasn’t it?

He went up the stairs, clutching the papers to his chest.

“She moved!” I said again, hesitant.

“I don’t speak English,” he said and slammed the door. It slid into the wall so hard it bounced back a little. I saw his shadow against the frosted glass of the door as he walked away.

Something oozed through the bottom of the sliding door, sluggish like dark blood.

Did Myu hit him that hard?

The liquid dripped down the stairs, and after a moment of panic, I realized it was ink, not blood. From the drawings she’d thrown, maybe, or a cartridge of ink he’d kept inside the notebook.

I stood for a minute watching it drip, thinking of the burning eyes of the girl staring at me, the same flame in Yuu’s eyes.

Had Myu seen it, too? Would anyone believe me? I wasn’t even sure what the heck I’d seen.

It couldn’t be real. I was too tired, overwhelmed in a country where I struggled to even communicate. That was the only answer.

I hurried toward the front door and out into the fresh spring air. Yuki and her friends had already vanished. I checked my watch—must be for a club practice. Fine. I was too jittery to talk about what I’d seen anyway. I ran across the courtyard, sans slippers this time, through the gate of Suntaba School and toward the weaving pathways of Sunpu Park.

When my mother died, it didn’t occur to me I would end up on the other side of the world. I figured they would put me in foster care or ship me up to my grandparents in Deep River, Canada. I prayed they would send me up there from New York, to that small town on the river I had spent almost every summer of my childhood. But it turned out that Mom’s will hadn’t been updated since Gramps’s bout of cancer five years ago, when she’d felt it was too much of a burden to send me there. And Gramps still wasn’t doing well now that the cancer had come back, so for now I would live with Mom’s sister, Diane, instead, in Shizuoka.

So much sickness surrounded me. I could barely deal with losing my mom, and then everything familiar slipped away.

No life in Deep River with Nan and Gramps. No life in America or Canada at all. I’d stayed with a friend of Mom’s for a while, but it was only temporary, my life stuck in a place where I couldn’t move forward or back. I was being shipped away from everything I knew, the leftover baggage of fading lives. Mom never liked leaving American soil, and here I was, only seven months without her, already going places she wouldn’t have followed.

And seeing things, hallucinating that drawings were moving. God, I’d be sent to a therapist for sure.

I told Yuki about the fight the next day during lunch, although I left out the part about the moving drawing. I still wasn’t sure what I’d seen, and I wasn’t about to scare off the only friend I had. But I couldn’t get it out of my mind, those sketched eyes glaring into mine.

I wouldn’t imagine that, right?

But the more I thought about it, the more dreamlike it felt.

Yuki turned in her seat to eat her

bentou

on my desk. I wasn’t used to the food yet, so Diane had packed my

bentou

box from side to side with squished peanut-butter sandwiches.

Yuki gripped her pink chopsticks with delicate fingers and scooped another bite of eggplant into her mouth.

“You’re kidding,” she said, covering her mouth with her hand as she said it. “I still can’t believe you went in there.”

She’d pinned her hair back neatly and her fingernails were nicely painted, reminding me of Myu’s delicate pink-and-silver nails. I wondered if they’d chipped when she hit him.

“You didn’t even wait for me to come out,” I said.

“Sorry!” she said, pressing her fingers together in apology.

“I had to get to cram school. Believe me, I was dying inside not knowing what happened.”

“I’m sure.” Yuki did like her share of drama.

She lifted her

keitai

phone in the air. “Here, send me your number. Then I can call you next time I abandon you in the middle of the biggest breakup of all time.”

I turned a little pink. “Um. I don’t have one?”

She stared at me a minute before shoving the cell phone back into her bag, then pointed at me. “Get one.

Maa,

I never realized Yuu Tomohiro was so mean.”

“Are you kidding? You told me he was cold!”

“I know, but I didn’t know he was cheat-on-your-girlfriend-and-get-someone-pregnant cold. That’s a different level.” I rolled my eyes, but secretly I tried to break down the number of words she’d just used. I loved that she had faith in my Japanese, but it was a little misplaced. We switched back and forth between languages as we talked.

Across the room, Yuki’s friend Tanaka burst through the doorway, grabbing his chair and dragging it loudly to our desks.

“Yo!”

he said, which sounded less lame in Japanese than English. He tossed his head to the side with a friendly grin.

“Tan-kun.” Yuki smiled, using the typical suffix for a guy friend. I looked down into the mess of peanut butter lining the walls of my

bentou.

Tanaka Ichirou was always too loud, and he always sat too close. I needed space to think about what I’d seen yesterday.

“Did you hear about Myu?” he said, and our eyes widened.

“How do you know?” said Yuki.

“My sister’s in her homeroom,” he said. “Myu and Tomo-kun split up. She’s crying over her lunch right now, and Tomo didn’t even show up for class.” Tanaka leaned in closer and whispered in a rough tone, “I heard he got another girl pregnant.”

I felt sick. I dropped my peanut-butter sandwich into my

bentou

and closed the lid.

That curve of stomach under the sketched blouse…

“He did!” Yuki squealed. It was all just drama to them.

But I couldn’t stop thinking about the way her head turned, the way she looked right at me.

“It’s just a rumor,” said Tanaka.

“It’s not,” Yuki said. “Katie spied on the breakup!”

“Yuki!”

“Oh, come on, everyone will know soon anyway.” She sipped her bottle of iced tea.

Tanaka frowned. “Weird, though. Tomo-kun might be the tough loner type, but he’s not cruel.”

I thought about the way he’d snatched the paper out of my hands. The sneer on his face, and the curve of his lips as he spat out his words.

Don’t you speak Japanese?

He seemed like the cruel type to me. Except that moment…that moment where he’d almost dropped everything and kissed Myu. His hand reaching for her chin, the softness in his eyes for just a second before it changed.

“How would you know?” I burst out. Tanaka looked up at me with surprised eyes. “Well, you called him by his first name, right?” I added. “Not even as a senior

senpai,

so you must know him pretty well.”

“Maa…”

Tanaka scratched the back of his head. “We were in Calligraphy Club in elementary school—you know, traditional paintings of Japanese characters. Before he dropped out, I mean. Which sucked, because he had a real talent. We haven’t really talked much since then, but we used to be close.

He got into a lot of fights, but he was a good guy.”

“Right,” I said. “Cheating on girls and making fun of foreigners’ Japanese. What a winner.”

Yuki’s face went pale, her mouth dropping open.

“He

saw

you?” She put a hand over her mouth. “And Myu?

Did she?”

I shook my head. “Just Yuu.”

“And? Was he angry?”

“Yeah, but so what? It’s not like I meant to spy on them.”

“Okay, we need to do damage control and see how bad your social situation is. Ask him about it after school, Tan-kun,” Yuki said.

I panicked. “No, don’t.”

“Why?”

“He’ll know I told.”

“He won’t know,” Yuki said. “Tanaka’s sister told him about the breakup, remember? We’ll just slip the conversation in and see how he reacts to you.”

“I don’t want to know, okay? Drop it please?”

Yuki sighed. “Fine. For now.”

The bell rang. We tucked our

bentous

into our bags and pulled out some paper.

Yuu Tomohiro. His eyes kept haunting me. I could barely concentrate on Suzuki-sensei’s chalkboard math, which was hard enough considering the language gap. Diane had been so set on sending me to a Japanese school instead of an international one. She was convinced I’d catch on quickly, that I’d come out integrated and bilingual and competitive for university programs. And since she knew how much I wanted to move back with Nan and Gramps, she wanted to hit me over the head with as much experience as possible.

“Give it four or five months,” she said, “and you’ll speak like a pro.”

Obviously she didn’t realize I was lacking in language skills.

When the final bell rang, I was relieved to find out I didn’t have cleaning duty. I had a Japanese cram school to go to, so I decided to cut through Sunpu Park and get on the east-bound train. I waved to Yuki, and Tanaka flashed a peace sign at me as he rolled up his sleeves and started lifting chairs onto the desks.

Pretty sure that counts as two friends,

I thought, and in spite of everything, a trickle of relief ran through me.

I headed toward the

genkan

to return my slippers—I wasn’t going to make that mistake again—and headed out into the courtyard.

School began in late March at Suntaba, and the spring air was fresh but cool. Green buds had crept onto each of the spindly branches of the trees, waiting for slightly warmer weather to bloom. Diane said everyone in Japan checked their cell phones daily to find out when the cherry blossoms would bloom so they could sit under them and get drunk.

Well, okay, that wasn’t exactly what she said, but Yuki said a lot of the salarymen turned as pink as the flowers.