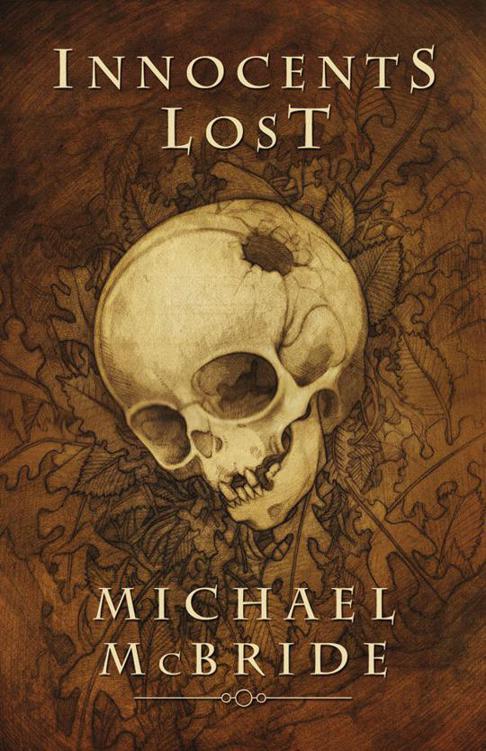

Innocents Lost

Authors: Michael McBride

INNOCENTS LOST

Michael McBride

For Cliff and Jane Gauthier, my grandparents

Special Thanks to Shane Staley, David Marty and Greg Gifune at Delirium; Brian Keene; Leigh Haig; Zach McCain; Gene O’Neill; Jeff Strand; Bill Rasmussen; Steve Souza; my amazing family; and to all of the Delirium collectors out there who’ve supported me through this, my fifth, DB title. Never has there been a more ravenous fan base. You guys are the greatest.

Prologue

June 20th

Six Years Ago

I

Evergreen, Colorado

“Happy Birthday to yooouuu.”

The song ended with laughter and applause.

“Make a wish, honey,” Jessie said. She raised the camera and focused on the child who was her spitting image: chestnut hair streaked blonde by the sun, eyes the blue of the sky on the most perfect summer day, and a radiant smile that showed just a touch of the upper gums.

Savannah wore the dress she had picked out specifically for her party, black satin with an indigo iridescence that shifted with the light. She rose to her knees on the chair, leaned over the cake, and blew out the ring of ten candles.

The camera flashed and the group of girls surrounding her clapped again.

“What did you wish for?” Preston asked.

“You know I can’t tell you, Dad. Sheesh.”

“Why don’t you girls run outside and play while I serve the cake and ice cream,” Jessie said. “And after that we can open

presents

.”

“All right!” Savannah hopped out of the chair and merged into the herd of girls funneling out the back door into the yard. More laughter trailed in their wake.

Preston crossed the kitchen and closed the door behind them.

“So are all eight of them really spending the night here?” he asked, glancing out the window over the sink as he removed a stack of plates from the cupboard. The girls made a beeline toward the wooden jungle gym. One had already reached the ladder to the tree house portion and another slid down the slide.

“Do you really think the answer will change if you ask enough times, Phil?” She took the plates from her husband, set them on the table, and began to cut the cake. “Besides, they’ll be sleeping in the family room with a pile of movies. The most we’ll hear from down the hall is a few giggles. Could you grab the ice cream from the freezer?”

“So what you’re saying is they’ll be distracted.” Preston eased up behind his wife, cupped her hips, and leaned into her.

She swatted his leg. “With a houseful of kids? Are you out of your mind?”

“I wasn’t proposing they watch.”

“Would you just get the ice—?”

The phone rang from the cradle on the wall.

Jessie elbowed him back, snatched the cordless handset, and answered while licking a dollop of frosting from her fingertip.

“Hello?”

Her smile vanished and her eyes ticked toward her husband.

“I’ll take it in the study,” Preston said. He removed the gallon of Rocky Road from the freezer, set it on the table, and hurried down the hallway.

“He’ll be right there,” Jessie said. Her voice faded behind him.

He ducked through the second doorway on the right and closed the door behind him. All trace of levity gone, he picked up the phone.

“Philip Preston,” he answered.

“Please hold for Assistant Special Agent-in-Charge Moorehead,” a female voice said. There was a click and then silence.

Preston paced behind his desk while he waited. He pulled back the curtains and looked out into the yard. Two of the girls twirled a jump rope on the patio for a third, while several others fired down the slide. Savannah and another girl arced back and forth on the swings. He couldn’t believe his little girl was already ten years old. Where had the time gone? In a blink, she had gone from toddler to pre-teen. In less than that amount of time again, she would be off on her own, hopefully in college—

“Special Agent Preston,” a deep voice said. He could tell by his superior’s tone that something bad must have happened.

Preston worked out of the Denver branch of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, thirty miles to the northeast of the bedroom community of Evergreen where he lived. The Lindbergh Law of 1932 gave the Crimes Against Children Division the jurisdiction to immediately investigate the disappearance of any child of “tender age,” even before twenty-four hours passed and without the threat that state lines had been crossed. As a member of the Child Abduction Rapid Deployment, or CARD, team, he was summoned to crime scenes throughout the states of Colorado and Wyoming, often before the local police. It was a depressing detail that caused such deep sadness that by the time he returned home, even his soul ached. But it was an important job, and at least at the end of the day, unlike so many he encountered through the course of his work, his wife and daughter were waiting for him with smiles and kisses in the insulated world he had created for them.

“Yes, sir.”

“Check your fax machine.”

“Yes, sir.” Preston allowed the curtains to fall closed and rounded his desk to where the fax machine sat on the corner. A stack of pages lay facedown on the tray. He grabbed them and took a seat in the leather chair, facing the computer. “Okay. I have it now. What am I—?”

His words died as he flipped through the pages. They were copies of slightly blurry photographs, snapped from a distance through a telescopic lens. Even though they were out of focus and the subjects partially obscured by the branches of a mugo pine hedge, he recognized them immediately.

“I don’t get it,” he whispered. “Where did these come from?”

“They arrived in the mail here at the Federal Building today. Plain white envelope. No return address. A handful of partial fingerprints we’re comparing against the database now. We’re tracking the serial numbers on the film to try to determine where they were processed.”

There were a dozen pictures. One of him approaching a small white ranch-style house. Another of him standing on the porch, glancing back toward the street while he waited for the door to be answered. Several of him talking to a disheveled woman, Patricia Downey, mother of Tyson, who had disappeared five hours prior. He didn’t need to check the date stamp to know that these had been taken nearly three months ago in Pueblo, just over a hundred miles south of Denver. No suspects. Loving mother and doting father, neither of whom had brushed with the law over anything more severe than a speeding ticket. Middle class, decent neighborhood. And an eight year-old boy who had never made it home from the elementary school only three blocks away, on a Thursday afternoon.

“This doesn’t make sense,” Preston said. “Why would anyone take these pictures, let alone mail them to us?”

He parted the blinds again and looked out upon the back yard. Nine girls still giggled and played. Savannah swung high, launched herself from the seat, and landed in a stumble. She barely paused before clambering back onto the swing.

“Look at the last one,” Moorehead said.

Preston’s stomach dropped with those somber words. He shuffled past a series of pictures that showed him walking back to where he had parked at the curb after the hour-long interview with the Downeys.

“Jesus.”

His heart rate accelerated and the room started to spin.

In one motion, he removed his Beretta from the recess in his desk drawer and jerked open the curtains again. Little girls still slid and jumped rope, but only one swing was occupied. The one upon which his daughter had been sitting only moments earlier swung lazily to a halt. As did the branches of the juniper shrubs behind the swing set.

“No, no, no!” he shouted.

The phone fell from his hand and clattered to the floor beside the faxed pages, the top image of which featured a snapshot of his house from across the street, centered upon Savannah as she removed a bundle of letters from the mailbox.

He ran down the hall and through the kitchen.

“Phil!” Jessie called after him. “What’s going on?”

He burst through the back door and hit the lawn at a sprint, nearly barreling into one of the girls twirling the rope.

“Savannah!”

The activity around him slowed. Two of the girls stared down at him from the top of the slide, faces etched with fear. He ran to the girl on the swing, a dark-haired, pigtailed slip of a child, and took her by the shoulders.

“Where’s Savannah?”

Startled, the girl could only shake her head.

Preston shoved away.

“Savannah!”

He shouldered through the hedge and hurdled the split-rail fence into the small field of wild grasses and clusters of scrub oak that separated the houses in this area of the subdivision.

“Savannah!”

A crunching sound behind him.

He whirled to see Jessie emerge from the junipers down the sightline of his pistol.

“What’s wrong?” she screamed. “Where’s Savannah?”

She must have read his expression, the panic, the sheer terror, and clapped her hands over her mouth.

Preston turned back to the field, tears streaming down his cheeks, trembling so badly he could barely force his legs to propel him deeper into the empty field toward the rows of fences and the gaps between them where paths led to the neighboring streets.

“Savannah!”

His voice echoed back at him.

He fell to his knees, rocked back, and bellowed up into the sky.

“Savannah!”

Chapter One

June 20th

Present Day

I

22 Miles West of Lander, Wyoming

“How much farther?” Lane Thomas asked. He swiped the sweat from his red face with the back of his hand.

Dr. Lester Grant had grown weary of the question miles ago. These graduate students were supposed to be the future of anthropology, and here they were braying like downtrodden mules.

“We’re nearly there,” Les said, comparing the printout of the digital photograph to the surrounding wilderness.

It was the summer session, so rounding up volunteers had been a chore, even though the opportunity to be published in one of the academic journals should have had them chomping at the bit. Granted, they had left the University of Wyoming in Laramie several hours before the sun had even thought about rising and driven for nearly three hours before they reached the end of the pavement and the rutted dirt road that wended up into the Wind River Range of the Rocky Mountains. Another hour of navigating switchbacks and crossing meadows where the road nearly disappeared entirely, and they reached the foot of the game trail that the hiker who had emailed him the photographs had said would be there. That was nearly two hours ago now. They’d taken half a dozen breaks already, and would be lucky if they’d managed to reach the three mile mark.

“Can we switch off again?” Jeremy Howard asked in a nasal, whiny tone. “Breck’s making it so that I’m bearing all of the weight.”

“Give me a break,” the blonde, Breck Shaw, said. She hefted the handles of the crate they carried between them for emphasis, causing Jeremy to stumble.

“That’s enough,” Les snapped. They were adults, for God’s sake. Sure, the crate containing the university’s magnetometer was quite heavy, but they all had to pay their dues, as he once had himself.

They proceeded in silence marred by the crackle of detritus underfoot.

The path had faded to the point that it was nearly non-existent. At first, it had been choppy with the hoof prints of deer and elk, but after they had crossed over the first ridge and forded a creek, it had grown smooth. Knee-high grasses reclaimed it in the meadows. Only beneath the shelter of the ponderosa pines and the aspens, where the edges of the trail were lined with yellowed needles and dead leaves, was it clearly evident. How had that hiker found this path anyway? They were hundreds of miles from the nearest town with a population large enough to support a Walmart Supercenter, and at an elevation where there was snow on the ground eight months out of the year. And this was so far out of the commonly accepted range of the Plains Indian Tribes, a generic title that encompassed the Arapahoe, Cheyenne, Crow, and Lakota, among others, that it made precious little sense for the site in the photographs to exist in the first place.

Which was what made the discovery so thrilling.

Les didn’t realize how accustomed he’d grown to the constant chatter of starlings and finches until the sounds were gone. Only the wind whistled through the dense forestation, the pine needles swishing as the branches rubbed together. The ground was no longer spotted with big game and rodent scat. Patches of snow clung to the shadows at the bases of the towering pines and beneath the scrub oak, evidence of what he had begun to suspect. The air was indeed growing colder.

An unusual tree to the left of the path caught his attention. The trunk of the pine had grown in a strange corkscrew fashion, almost as though it had been planted by some omnipotent hand in a twisting motion. He fingered the pale green needles, which hung limply from branches that stood at obscene angles from the bizarre trunk.

“Can we take a quick break so I can get my coat out of my backpack?” Breck asked.

Les didn’t reply. He was focused on an aspen tree several paces ahead. It too had an unusual spiral trunk. What could have caused them to grow in such a manner? He was just about to run his palm across its bark, which looked like it would crumble with the slightest touch, when he noticed the large mound of stones at the edge of the clearing ahead.

“We’re here,” he said.

He slipped out of his backpack and removed his digital camera.

“It’s about time,” Lane said. “I was starting to think we might have walked right past…”

The student’s words were blown away by the wind as Les walked past the first cairn and began snapping pictures. The clearing was roughly thirty yards in diameter. More corkscrewed trees grew at random intervals. They weren’t packed together as tightly as those in the surrounding forest, but just close enough together to partially hide the constructs on the ground from the air. There were more mounds of stones in a circular pattern around the periphery of the clearing, all piled nearly five feet tall. He paused and performed a quick count. There were twenty-seven of them, plus a conspicuous gap where there was room for one more. Short walls of stacked rocks, perhaps a foot tall, led from each cairn to the center of the ring like the spokes of a wagon wheel. The earth between them was lumpy and uneven. Random tufts of buffalo grass grew where the sun managed to reach the dirt, which was otherwise barren, save for a scattering of pine needles.

“Why don’t you guys start setting up the magnetometer,” he called back over his shoulder as he stepped over the shin-high stack of stones that had been laid to form a complete circle just inside the twenty-seven cairns, and approached the heart of the creation.

At the point where the spokes met, more twisted trees surrounded a central cairn, which was wider and taller than the others. As he neared, Les could tell that it wasn’t a solid mound at all, but a ring.

The formation of stones was a Type 6 Medicine Wheel like the one at Bighorn in the northern portion of the state, only on a much grander scale. Medicine wheels had been found throughout the Rocky Mountains from Wyoming all the way north into Alberta, Canada. They predated the modern Indian tribes of the area, which still used them for ceremonial rituals to this day. No one was quite certain who originally built them or for what purpose, only that they were considered sacred sites by the remaining Native American cultures, all of which had various myths to explain their creation. If this was a genuine medicine wheel, then it would be the southernmost discovered, and the most elaborate by far.

The emailed photographs had given him no reason to question its authenticity; however, now that he saw it in person, he was riddled with doubt. The stone formations were too well maintained. Not a single rock was out of place, nor had windblown dirt accumulated against the cairns to support an overgrowth of wild grasses. No lichen covered the stones, which, upon closer inspection, appeared to be granite. And the pictures had been taken in such a manner as to exclude the odd trunks.

Here he was, standing in the middle of what could prove to be the anthropological discovery of a lifetime, and he suddenly wished he’d never found this place. It was an irrational feeling, he knew, but there was just something…wrong with the scene around him.

He reached the center of the clearing and used the coiled trunk of a pine to propel himself up to the top of the ring of stones. The ground inside was recessed, the inner stones staggered in such a way as to create a series of steps. And at the bottom, in the dirt, saved from the wind, was a jumble of scuff marks preserved by time. The aura of coldness seemed to radiate from within it.

“Dr. Grant,” Jeremy called from the tree line. “We need a little help setting up this machine.”

“You’re just trying to force that piece where it doesn’t belong,” Breck said.

“Then you do it, Little Miss Know-It-All.”

Les sighed and climbed back down from what he had unconsciously begun to think of as a well, and headed back to join the group. For whatever reason, he dreaded assembling the magnetometer.

He suddenly feared what they would find.

II

Evergreen, Colorado

Preston sat in his forest-green Jeep Cherokee, staring across the street toward the dark house. He couldn’t bring himself to go in there. Not today. But he couldn’t force himself to leave yet either. Once upon a time, it had been his home, a place filled with love and laughter. Now it was a rotting husk, a shadow of its former self. The white paint had begun to peel where it met the trim, and there were gaps in the roof where shingles had blown away. The hedges in the yard had grown wild and unkempt, the lawn feral.

His life had ended in that house. The world had collapsed in upon itself and left him with nothing but pain.

And it had been all his fault.

His child, the light of his life, had been stolen from him because of his involvement in a case, and he still didn’t know why. Over the last six years, he had begun to piece together a theory. Unfortunately, that’s all it was. A theory. Grasping at straws was what his superiors had called it. Over the past year, nearly eight hundred thousand children were reported missing. While most were runaways, more than a third of them were abducted by family members or close friends. Many of these children resurfaced over the coming weeks, while still others never did. It was the smallest segment, the children who vanished at the apparent hands of strangers, that was the focus of his attention. At least privately. Professionally, he performed his job better than he ever had. After Savannah’s abduction, he had thrown himself into it with reckless abandon, and at no small personal sacrifice. On a subconscious level, he supposed he hoped that by helping to return the missing children to their frightened parents that the universe might see fit to return his to him. But there was more to it than that. It was a personal quest, an obsession, and it had finally led him to a pattern.

Factoring out all of the kidnappings for ransom, the abductions by estranged parents or family friends, and the crimes of opportunity, where the child was simply in the wrong place at the wrong time, left Preston with a much smaller field to investigate. By narrowing his scope further to encompass only missing children from stable, two-parent, at least superficially loving homes, he winnowed the cases in his jurisdiction down to a handful each year. And of those, if he set the age range at Savannah’s at the time of her disappearance, plus-or-minus three years, he was left with four cases annually over the past six and a half years. Not an average of four. Not three one year and five the next. Exactly four. And they were spread out by season. One child each year in the spring, another in the summer, a third in the fall, and a fourth in the winter. And all within two weeks of the four most important dates on the celestial calendar—the vernal and autumnal equinoxes, and the summer and winter solstices.

The kidnappings were the work of a single individual: the man who had stolen his daughter from him. The same man who had sent the photographs of him at the Downey house, who had been within fifty yards of him at a point in time when if Preston had known, he could have prevented the abduction of his cherished daughter, and the twenty-three children who came after her, with a single bullet.

Why could no one else see it? Why didn’t they believe him?

Because he knew all too well that the parents of missing children would say or do anything if there was a chance of learning the fate of their son or daughter, even if it meant formulating a theory from a set of points that on paper appeared completely random, like forming constellations from the stars in the night sky.

Preston focused again on the house, but still couldn’t bring himself to press the button on the garage door opener and pull the idling Cherokee inside. There was only solitude waiting for him within those walls, and the heartbreaking memories he was forced to endure with every breath he took. The house was a constant reminder of the greatest mistake of his life, but more than that, it was a beacon, the only location on the planet that Savannah had ever called her own. He still held out hope that wherever she was, one of these days she would simply appear from nowhere and return to her home. To him. It was the reason he would never allow himself to sell it. The one wish he allowed himself to pray would come true.

It was all he had.

He slid the gearshift into drive and headed south, pretending he didn’t know exactly where he was going. Ten minutes later he was on the other side of town, parked in front of a Tudor-style two-story, upon which the forest encroached to the point of threatening to swallow it whole. Light shined through the blinds covering the windows. With a deep breath, he climbed out of the car and approached the porch.

The house positively radiated warmth, reminding him of what should have been. He pressed the doorbell and backed away from the door.

Shuffling sounds from the other side of the door, then a muffled voice.

“Just a second.”

The door opened inward. A woman stood in the entryway, cradling a swaddled baby in the crook of her left arm. She brushed a strand of blonde bangs out of her eyes with the back of her right hand, which held a bottle still dripping from recently being heated in boiling water.

“Hi, Jessie,” he said.

She still had the most amazing eyes he’d ever seen.

“Philip,” she whispered. “You shouldn’t be here.”

“He’s beautiful, Jess.” He nodded to the baby. “How old is he by now?”

“Phil…”

They stood in an awkward silence for several long moments.

“You remember what today is?” Preston finally asked.