Insectopedia (53 page)

* * *

Far to the southwest, the Inca ruler Huayna Capac was touring the limits of his empire. Arriving at Pasto, a frontier outpost close to today’s border between Colombia and Ecuador, he supervised the building of defenses and pointed out to the leaders of the district that as a consequence of the empire’s investment in their welfare, they were now in his debt. According to Pedro de Cieza de León, one of the most important Spanish chroniclers of the Incas, the local notables replied that they were entirely without the means to meet new taxes.

Resolved to teach these lords of Pasto the reality of their situation, Huayna Capac issued instructions that “each inhabitant should be obliged, every four months, to give a rather large cane full of live lice.” Cieza de León says that the lords laughed out loud when they heard this command. Soon enough, though, they learned that no matter how diligent they were in collecting, they were unable to fill the designated baskets. Huayna Capac provided them with sheep, writes Cieza de León, and it wasn’t long before Pasto was providing Cuzco, the Inca capital, with its full complement of wool and vegetables.

18

* * *

Further south, the Urus retreated to floating reed islands in Lake Titicaca in an effort to stave off Inca conquest. (These artificial islands and the few people who live on them are today one of the area’s principal tourist attractions.) The chroniclers report that the Incas regarded the Urus as so

lowly that the word with which they named them meant “maggot.” The same accounts explain that the Incas levied the Urus’ tribute in lice simply because they considered them unfit to pay in any other currency.

19

* * *

Nothing like this is documented for the Wari, the Maya, the Mixtec, the Zapotec, or the other great pre-Columbian empires. Often the records are just too scant. However, it is known that in battle the Maya were able to create a formidable panic among their enemies by bombarding them not with lice, but with missiles constructed from live wasps’ nests.

20

From a remote district of mountainous Guangxi Province, the renowned Tang-dynasty poet and philosopher Liu Zongyuan described the character of owl-fly larvae.

* * *

Owl-flies are ancient creatures. They have been identified in amber from the Dominican Republic that is more than 45 million years old.

21

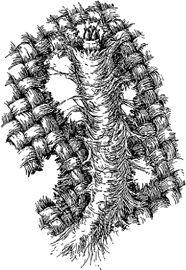

The adults resemble dragonflies, but the larvae look like the larvae of ant lions: they have dark-brown oval armored bodies about an inch long, with powerful pincer-shaped mandibles. Unlike ant lion larvae, which set a shallow trap in sandy soil and lie in wait for ants and other prey to drop in, owl-fly larvae camouflage themselves by pulling debris over their bodies. Only the outsize mandibles remain uncovered. When an insect wanders too close, the large jaws snap shut, and the larva sucks the pinioned body dry.

* * *

In

A.D.

805, Liu Zongyuan was banished from the cosmopolitan imperial capital of Chang’an (present-day Xi’an) for his involvement in a failed

reformist coup. Chang’an, says Liu’s biographer Jo-shui Chen, was “the ‘hometown’ to which he dreamed of returning” but never would.

22

In “My First Excursion to West Mountain,” one of the eight short essays he completed between 809 and 812 that are “considered to have inaugurated the genre of the lyric travel account,” Liu wrote:

I have been in a state of constant fear since being exiled to this prefecture. Whenever I had a free moment, I would roam about, wandering aimlessly. Every day I hiked in the mountains accompanied by friends with similar fates. We would penetrate into the deep forests, following the winding streams back to their source, discovering hidden springs and fantastic rocks—no spot seemed too remote. Upon reaching a place, we would sit down on the grass, downing bottles of wine until we were thoroughly drunk. Drunk, we would lean against each other as pillows and fall asleep. Asleep, we would dream.

23

Liu died in 819 at the age of forty-six. More than 500 years later he would be recognized as one the eight masters of Tang and Song dynasty prose.

The year he died, in

A Record of Fu Ban

, he described how, when an owl-fly larva catches its prey, it carries it “forward with its chin up.”

Its load is getting heavier and heavier. Though very tired, [the larva] does not fall down as it cannot rise to its feet once it has stumbled. Some people take pity on it and lift off the load so the insect can continue walking forward. However, it soon takes on its burden once again.

24

* * *

Elsewhere during these years of exile, in a meditation on the nature of heaven and human responsibility, Liu Zongyuan asks: “Were someone to succeed in exterminating the insects that eat holes in things, could these things pay him back? Were someone to aid harmful creatures in breeding and proliferating, could these things resent him?”

No, of course not, he says. The fact of the matter is that “merit is self-attained and disaster is self-inflicted.” He is near the end of his time in this melancholy place. “Those who expect rewards or punishments are

making a big mistake.… You should just believe in your [principles of] humanity and righteousness, wander in the world according to these principles, and live [in this way] until your death.”

25

After the defeat of the Nazis, Karl von Frisch returned to Munich to resume his work as director of the Institute of Zoology. In 1947, he published

Ten Little Housemates

, a small book for nonscientific readers in which he tried to show that “there is something wonderful about even the most detested and despised of creatures.”

26

* * *

He begins with the housefly (“a trim little creature”) and moves on to mosquitoes (which, he admits, “can never be pleasant”), fleas (“An adult man wanting to compete with a flea would have to clear the high-jump bar at about 100 metres and his long-jump would have to measure about 300 metres.… At one jump he could leap from Westminster Bridge to the top of Big Ben”), bed bugs (“We must remember that all living creatures are equal in the eyes of the great law of life: men are not superior to mice nor bugs to men”), lice (“With its forefeet alone a louse can carry up to two thousand times the weight of its body for a whole minute. This is more than the strongest athlete could ever hope to do; it would mean holding up a weight of 150 tons in his hands!”), the cockroach (“a community that has come down in the world”), silverfish (“

Lepisma saccharina—

the sugar guest.… They are entirely harmless housemates”), spiders (“It is astonishing how little the inborn [web-making] skill of these animals is bound to a rigid system, how greatly their actions differ in detail according to local conditions and according to the weaver’s character”), and ticks (“As there is good reason for the female’s bloodthirstiness, we cannot blame her. Anyone who has to hatch out a few thousand eggs can do with a good meal”).

* * *

Von Frisch devotes one of his longer chapters to his tenth housemate, the clothes moth. He begins with the caterpillar. Like the dung beetle, it turns out to be an essential scavenger, feeding off the planet’s suffocating mountains of surplus hair, feathers, and fur. Like the caddis fly larva, it fashions itself a protective case, spinning a tiny silken tube, a minute padded sock, which it covers with trimmings from the keratin-based world around it. To eat, it peeks its head out of the tube and nibbles the landscape beside the opening. When everything within reach is gone, it explores by extending its case further into the underbrush.

Soon the caterpillar is fully grown and leaves its tube. Awkwardly, it makes its way to a new location, from which the moth will easily be able to take to the air. Maybe it’s the surface of your grandmother’s fur coat or perhaps your favorite winter sweater. Once it arrives, the caterpillar spins itself a new home, gussies it up as before, and prepares for pupation.

* * *

Like many lepidoptera, the adult clothes moth cannot eat or drink. In its few weeks of life, it exhausts the energy stores it accumulated as a caterpillar, losing 50 to 75 percent of its body weight in the process. The female, heavy with up to 100 eggs, is reluctant to fly and spends her days hiding in the dark. Von Frisch is irritated by uninformed violence. “When a lively moth flies around the room,” he says, “there is no point in the whole family chasing it. It is only a male. There are plenty of male moths, actually about double the number of females. So the birthrate will not be affected if a few more or less are killed.”

27

* * *

Von Frisch’s little housemates are extraordinary and, in their own ways, exceptional. He explores the extremes of their existence, explains their

extravagances, examines their exuberances, and excluding exaggeration, exalts in their extravagations. With his characteristic exactitude, he examines his own experiments and expands on his experiences. In extensive and exhaustive excurses—often external to the exegesis—he extends excuses and extenuations for their excesses. Still, each of his chapters ends with recommendations for his little housemates’ extirpation, that is, for their extermination.

Houseflies should be trapped on flypaper or poisoned. Clothes moths are susceptible to naphthalene and camphor. Silverfish can be controlled with DDT (which “does not harm human beings or domestic animals if it is used in reasonable quantities and according to the instructions”). Lice should be mass-killed by fumigation with prussic acid and its derivatives (“one useful product of the war”). Mosquitoes require more drastic measures: you should drain their wetland habitats, flood the area with petroleum, or introduce predatory fish into their breeding pools. DDT should also be used against cockroaches.

“It is doubtful whether insects feel pain at all as we do,” says von Frisch. And he tells a story to demonstrate his claim. He goes back to his beloved bees, the little comrades to whom he devoted his adult life. “If you take a pair of sharp scissors,” he begins, “and cut a bee in two, taking care not to disturb it while it is taking a drop of sugary water, it will go on eating.”

28

Von Frisch’s even, good-natured tone doesn’t change. Roger Caillois encountered something like this too, something that brought death, pleasure, and pain into one claustrophobic space. But Caillois, conscripted by a different type of science, found himself bound and subject to his animal: “I am deliberately expressing myself in a roundabout way,” he wrote as he tried to explain the peculiar power of the praying mantis, “as it is so difficult, I think, both for language to express and for the mind to grasp that the mantis, when dead, should be capable of simulating death.”

29

But the bee just keeps on drinking. It doesn’t seem to raise questions beyond the experiment. It appears to have lost its magic. Its “pleasure—if it feels any—is even considerably prolonged,” von Frisch observes. “It cannot drink its fill, for what it sucks trickles out again at the rear, and hence it can feast on the sweetness for a long time before it finally sinks dead of exhaustion.”

30

Ex-animal, ex animo. He extends, exhibits, and exanimates. It excretes, exhales, and expires.

But let’s not forget: just as there are forms of the marvelous that thrive on knowledge, there is knowledge that despite itself adds to the marvelous; just as there are those who underestimate the lowly multitude, there are people who understand only too well its many-sided power; just as there are those who subject the animal to the steel of experiment, there are those who take pity and lift off its load, even though it soon takes on its burden once again.

earnings

1.

Kawasaki Mitsuya sells live beetles on the Internet. My friend Shiho Satsuka found his site and, knowing it would get my attention, sent me the link. A few weeks later, I was in the suburbs of Wakayama City, outside Osaka, with my friend CJ Suzuki, sitting in Kawasaki’s insect-filled living room and talking about

ookuwagata

, the Japanese stag beetles in which he trades.

Kawasaki Mitsuya recently gave up his job as a hospital radiographer, but there’s no money in stag beetles, he tells us. He opens some jars and explains that he does this for love. He fills his website with his poems. Some are silly, some are cute, some are abruptly bitter, even angry. Most are melancholy laments that contrast middle-aged male disillusion with the innocent openness of youth. (“He looks at the sky and the blue stays in his eyes. / The eyes of a child are like glass balls that truthfully reflect the world. / The eyes of the grown man have lost their light, / His eyes are cloudy like stagnant pools.”)

1