Insomnia and Anxiety (Series in Anxiety and Related Disorders) (33 page)

Read Insomnia and Anxiety (Series in Anxiety and Related Disorders) Online

Authors: Jack D. Edinger Colleen E. Carney

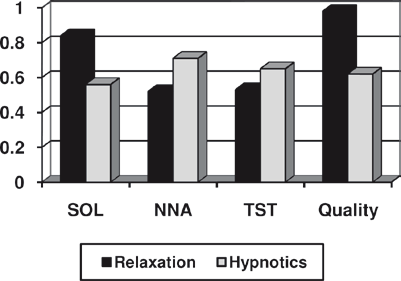

a well-established and efficacious treatment for insomnia management. Results

of meta-analyses (Morin, Culbert, & Schwartz, 1994; Murtagh & Greenwood,

1995), for example, suggest that relaxation therapy, in general, results in mod-

erate to large treatment effect sizes (compared to control conditions) when

common subjective sleep measures such as sleep onset latency, total sleep time,

sleep quality, etc., are considered. Furthermore, the sleep improvements result-

ing from relaxation therapy compare favorably with those obtained with com-

mon hypnotic medications. Figure 9.1 shows findings from meta-analyses for

relaxation therapy (Murtagh & Greenwood, 1995) and hypnotic medications

(Nowell et al., 1997). Specifically, this figure compares the effect sizes obtained

from the two types of therapies for subjective estimates of sleep onset latency

(SOL), number of nocturnal awakenings (NNA), total sleep time (TST), and

sleep quality. These findings suggest that hypnotic medications have modest

advantages over relaxation approaches on measures of TST and NNA, but

relaxation therapies produce much larger improvements in SOL and sleep qual-

ity ratings than do the medications. Moreover, it should be noted that the results

shown in the Figure were derived from short-term therapy (average = seven 7

days) with hypnotics, and there are currently no data to show that brief hypnotic

intervention leads to long-term sleep improvements once such medication is

withdrawn. In contrast, results obtained with relaxation tend to endure well

after acute treatment (i.e., therapist contact) ends. Hence, due to the durability

Relaxation-Based Strategies

125

Fig. 9.1

Effect sizes for relaxation and

hypnotic therapies

of its treatment effects, relaxation therapy may be preferred over hypnotic

medications for the management of patients with chronic insomnia.

Treatment approach

: Over the years, various forms of relaxation therapy have

been tested for insomnia management. Included among these are techniques

such as progressive muscle relaxation, passive relaxation, autogenic training,

deep breathing, EMG and EEG biofeedback, various forms of meditation, and

use of relaxing imagery. Head-to-head studies designed to identify the best

approach generally have been absent from the literature, and cross-study com-

parisons have failed to suggest that one approach is a clear winner over the other

approaches for treating insomnia (Murtagh & Greenwood, 1995). However, a

perusal of the literature shows that progressive muscle relaxation (PMR) training

has been the most commonly employed form in previous treatment studies.

Given that observation, we have chosen to include instructions for that form of

relaxation training in this chapter.

Both the literature and our own clinical experience suggest that a number of factors

should be considered when selecting and preparing patients for this form of treatment.

First, it should be noted that relaxation therapy has its most pronounced positive

effects among those with sleep onset difficulties (Murtagh & Greenwood, 1995)

and may be less effective as a stand-alone approach than are multicomponent CBT

protocols for sleep maintenance difficulties (Edinger, Wohlgemuth, Radtke, Marsh,

& Quillian, 2001). Secondly, people with insomnia generally appear more receptive

to relaxation treatment if they are provided a convincing rationale for this intervention.

In this regard, a brief explanation of the role of excessive arousal as a perpetuating

mechanism and the effectiveness of relaxation for reducing arousal is often useful.

Finally, this treatment requires a significant amount of home-based practice between

treatment sessions to achieve the treatment effects desired. For that reason, people

must be relatively committed and adherent to the treatment process. Those who have

demonstrated adherence difficulties to other aspects of treatment may not be the best

candidates for this form of intervention.

126

9 Other Issues in Managing the Sleep of Those with Anxiety

Assuming proper candidacy for PMR, it is usually useful to introduce the

therapy with the following sort of rationale:

“To understand the reason for using the strategy we are about to discuss, it is important that

you learn how a sleep problem like yours develops. Usually, insomnia problems begin as a

result of stressful life events or disruption of one’s usual sleep patterns. At first, an indi-

vidual may ignore or minimize the sleep difficulty. However, if the stressor or disrupting

agent lasts long enough, concern about the sleep disruption usually develops. This concern

usually takes the form of worrying about not sleeping, becoming anxious, watching the

clock, tossing and turning, etc. By repeatedly pairing these activities with attempts to sleep,

the act of trying to sleep becomes associated with a heightened state of arousal that only

serves to make sleep difficult to initiate. Since this “conditioned arousal” is learned over

time, it can also be unlearned. One method for accomplishing this is by pairing a state of

relaxation, rather than arousal, with your attempts to sleep. Over the course of this treat-

ment you will be taught relaxation skills that will help you overcome any heightened

arousal you experience when you are awake in bed. These skills should help you fall sleep

more quickly on a routine basis.”

This treatment rationale helps clarify the role of PMR in the management of insomnia

and typically increases the likelihood that the person will both accept the approach

and continue the practice outside of the therapy session.

In conducting the therapy, it is helpful to provide a therapeutic environment that

is conducive to the PMR process. As noted in the classic PMR manual (Bernstein

& Borkovec, 1973), people should wear sufficiently comfortable clothing so that

their attire does not hinder the relaxation process. In preparing for the RT exercise,

eyeglasses or jewelry should be removed that could distract during the training.

Also, they should be encouraged to use the restroom prior to each training session,

so that they are most comfortable when undergoing RT training. A quiet room

equipped with a recliner chair is desirable for PMR sessions. It may be optimal to

sit in a recliner with eyes closed and legs raised off of the floor during the delivery

of instructions by the therapist. While PMR instructions are being presented, the

room lighting may be dimmed if possible to facilitate the training process.

Consistent with the training protocol described by Bernstein and Borkovec

(1973), PMR begins by teaching exercises involving the alternate tensing and

relaxing of 16 skeletal muscle groups. Subsequently, they are taught how to combine

the initial 16 muscle groups into 7 and later 4 muscle groups. Finally, the tensing

portion of the exercise is dropped, and patients learn how to relax their muscles

without first tensing them. The outline below shows the progression from one exercise

to the next across the 6 RT treatment sessions.

PMR Treatment Outline

Session 1

Present rationale

Introduction of progressive muscle relaxation

PMR exercise – 16 muscles (tension-release)

(continued)

PMR Treatment Outline

127

(continued)

Home practice instructions

Session 2

Review home practice

PMR exercise – 16 muscles (tension-release)

Home practice instructions

Session 3

Review home practice

PMR exercise – 7 muscles (tension-release)

Encourage use of RT to combat nocturnal wakefulness

Session 4

Review home practice

RT exercise – 4 muscles (tension-release)

Same as C. for Session 3

Sessions 5 and 6

Same as Session 3

RT exercise – 4 muscles (relax only)

Same as C. for Session 3

In most respects, PMR training in those with insomnia is no different from training

conducted with other types of patients deemed suitable for this intervention. Although

some attention to the insomnia problem is usually included in presenting treatment

instructions, most of the protocol includes the standard PMR instructions that are

employed with myriad anxiety and stress-induced conditions. The following script and

instructional guidelines demonstrate how PMR is fashioned for insomnia sufferers:

“The exercise you are about to learn is called progressive muscle relaxation. This exercise

should help you overcome the conditioned arousal you experience when you awaken

during the night so that you can return to sleep more easily. Relaxation therapy is useful

for a variety of stress-related conditions including tension headache, high blood pressure,

general anxiety and insomnia.

During this first treatment session you will be taught an exercise that requires you to

alternately tense and relax 16 major muscle groups throughout your body. In doing so,

you will become sensitized to your muscle tension and better able to rid yourself of

unwanted tightness. Also, by tensing each muscle group first, you will give yourself a

‘running start’ toward deep relaxation because the tension release will provide you some

momentum toward this state.

Before beginning this exercise, you should understand that relaxation is a skill. Like any

other skill such as riding a bicycle, typing, knitting or playing golf, progressive relaxation

requires practice. You will, hence, be asked to practice this procedure at home every day.

Only through such practice will you become able to use relaxation to combat your nocturnal

awakenings. Now, before we begin the exercise, do you have any questions?

After pausing to answer any questions:

OK, now let’s begin. I would like you to first make yourself comfortable in the chair by

raising the footrest to a comfortable height. Now close your eyes and clear your mind so

that you can concentrate only on my voice (10 sec. pause). To begin, focus all of your

attention on the muscles in your dominant hand and forearm. When I tell you, you will

tighten these muscles by making a tight fist. OK, tense these muscles now (pause 7 sec.)

Now relax your hand and forearm by opening your fist. As you do so, study the sensations

128

9 Other Issues in Managing the Sleep of Those with Anxiety

in your hand and forearm. Notice how the tension feels different from the relaxation.

Continue to relax your hand and forearm and study the sensations (after 30-40 sec of relax-

ation “patter” the tension [7 sec] and relaxation [30-40 sec.] is repeated with the hand and

forearm).

Now that you have tensed and relaxed your hand and forearm, focus your attention on the

bicep in your dominant arm. You will tense this muscle by bending your arm at the elbow

and pushing your elbow against the chair. Ok tense your bicep now and study how the

tension feels (pause 7 sec.). Now release the tension and notice how different the tension

and relaxation feel. Also compare the relaxation you feel in your bicep with the relaxation

you achieved in your hand and forearm. Continue to relax your bicep and when you feel

that it is as relaxed as your hand and forearm signal me by raising the index finger of your

dominant hand slightly (after 30-40 sec. of relaxation, the tension [7 sec.] and relaxation

[30-40 sec.] is repeated with the bicep.)”

At this point in the exercise, the above script is repeated substituting the nondominant

hand/forearm and bicep in these instructions before moving on to the following

instructions involving the face muscles.

“Having tensed and relaxed the muscles in your hands and arms, we will now move on to

the muscles in your face. You should begin by focusing on the muscles in your upper face.

You will tense these muscles by raising your eyebrows as high as possible. OK tense these

muscles now. Feel the tightness in your upper face as you do that (7 sec. pause). Now relax