Inverting the Pyramid: The History of Football Tactics (12 page)

Read Inverting the Pyramid: The History of Football Tactics Online

Authors: Jonathan Wilson

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #History

Vicente Feola, the Brazil coach who introduced 4-2-4 to the world (

Getty Images

)

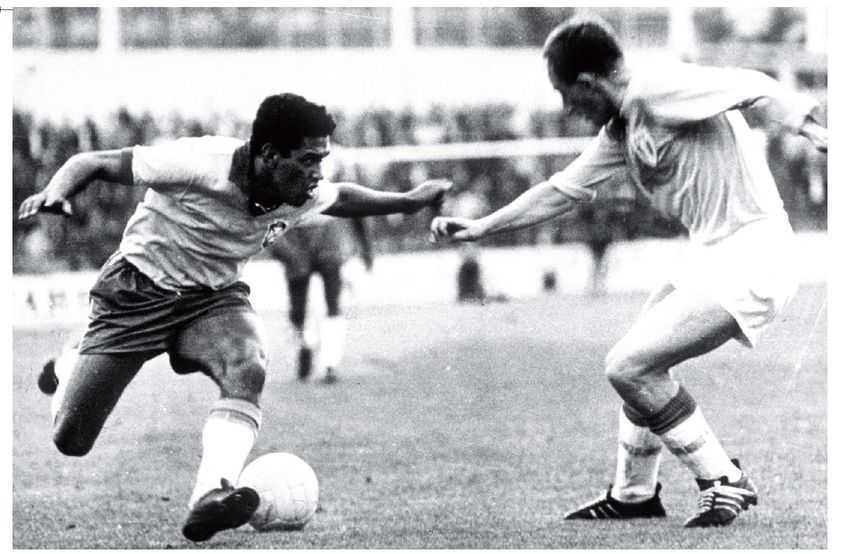

Garrincha, the winger whose anarchic style flourished in the 4-2-4 (

Getty Images

)

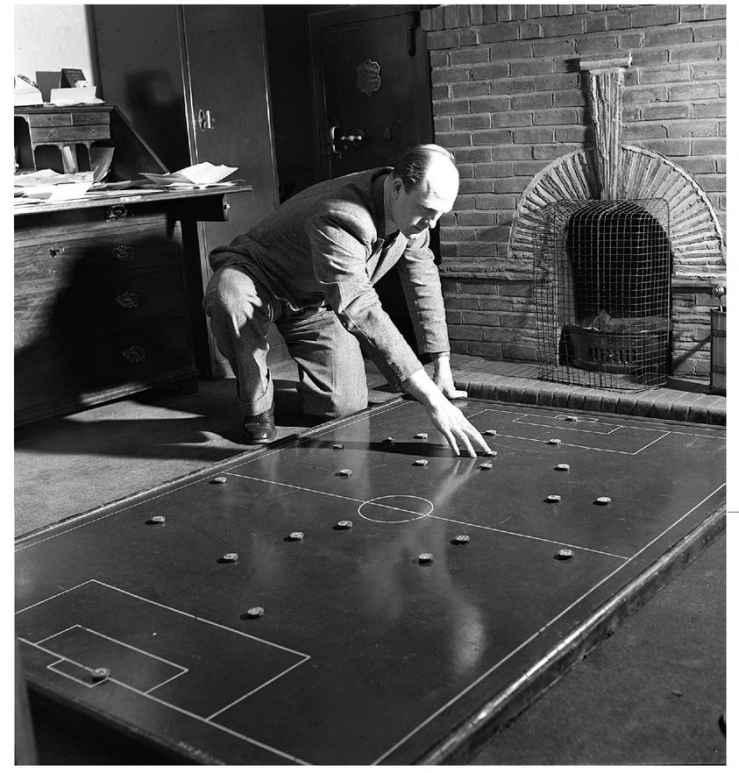

Stan Cullis devises another tactical masterplan for Wolves (

Getty Images

)

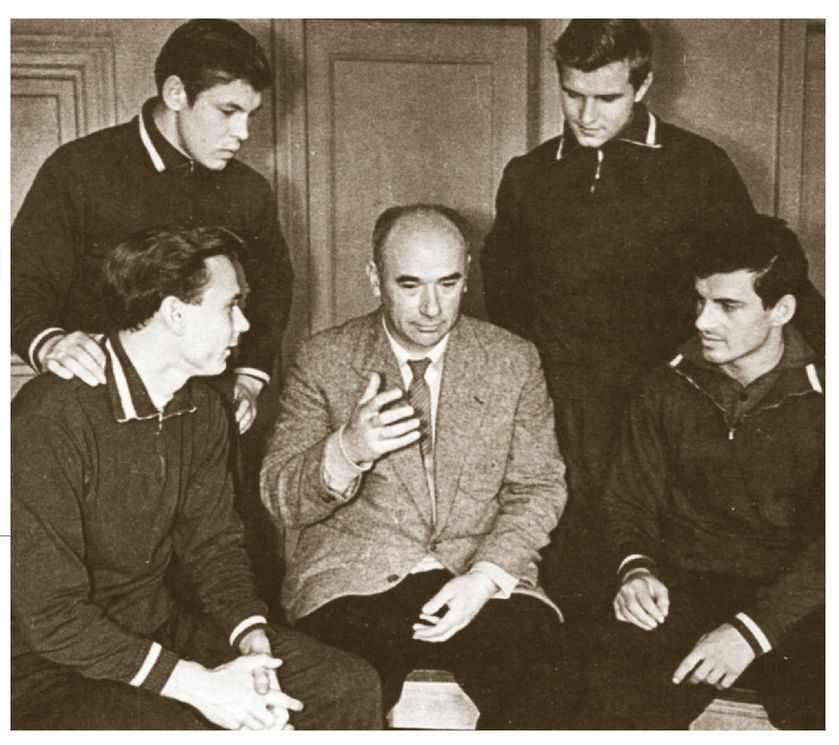

Viktor Maslov talks his Torpedo players through his latest stratagem (

Pavel Eriklinstev

)

All that changed in 1937. The coming of the national league perhaps would have led to more sophisticated analysis of the game anyway, but the trigger for development was the arrival of a Basque side on the first leg of a world tour aimed at raising awareness of the Basque cause during the Spanish Civil War.

Because of their rarity, matches against foreign sides were always eagerly anticipated, all the more so in 1937 after the release the year before of

Vratar

(

The Keeper

), Semyon Timoshenko’s hugely popular musical-comedy about a young working-class boy - played by the matinee idol Grigori Pluzhnik - selected for a local side to play against a touring team having been spotted catching a watermelon as it fell from a cart. Predictably, if ridiculously, after making a series of fine saves, the hero runs the length of the field in the final minute to score the winner. The film’s most famous song rams home the obvious political allegory: ‘Hey, keeper, prepare for the fight/ You are a sentry in the goal./ Imagine there is a border behind you.’

The real-life tourists, though, featuring six of the Spain squad from the 1934 World Cup, were no patsies for Soviet propaganda and, employing a W-M formation, hammered Lokomotiv 5-1 in their first game. Dinamo were then beaten 2-1 and, after a 2-2 draw against a Leningrad XI, the Basques returned to Moscow to beat the Dinamo Central Council’s Select XI 7-4. Their final game in Russia saw them face Spartak, the reigning champions. Determined to end the embarrassment, the head of Spartak’s coaching council, Nikolai Starostin, called up a number of players from other clubs, including the Dynamo Kyiv forwards Viktor Shylovskyi and Konstantyn Shchehotskyi, who had starred in a Kyiv Select XI’s 6-1 victory over Red Star Olympic - a rare game against professionals - on a tour of Paris in 1935.

Starostin decided to match the Basques shape-for-shape, converting his centre-half into a third back to try to restrict the influence of Isodro Langara, the Basque centre-forward. As Starostin records in his book

Beginnings of Top-level Football

, the move was far from popular, with the most vocal opponent being the centre-half, his brother Andrei. ‘“Do you want me to be famous across the whole Soviet Union?” he asked. “You are denying me room to breathe! Who will help the attack? You are destroying the tactic that has been played out for years…”’

This was not, though, Spartak’s first experiment with a third back. A couple of years earlier, injuries on a tour of Norway had forced them to tinker with their usual 2-3-5. ‘Spartak used a defensive version of the W-M by enhancing the two backs with a half-back,’ Alexander Starostin, another of the brothers, said. ‘When necessary, both the insides drew back.’ Impressed by the possibilities of the system, Spartak briefly continued the third-back experiment as they prepared for the 1936 spring season. ‘That thought, brave but unpopular in the country, was ditched after a 5-2 defeat to Dinamo [Moscow] in a friendly,’ Nikolai Starostin said. ‘Now came the second attempt, again in a friendly, but this time in a very important international encounter. It was a huge risk.’

And not just from a sporting point of view. The authorities took the game so seriously that in the build-up, Ivan Kharchenko, the chairman of the Committee of Physical Culture, Alexander Kosarev, the head of Comsomol (the organisation of young Communists) and various other party officials slept at Spartak’s training base at Tarasovka. ‘Spartak was the last hope,’ Nikolai Starostin wrote in his autobiography,

Football Through the Years

. ‘All hell broke loose! There were letters, telegrams, calls giving us advice and wishing us good luck. I was summoned to several bosses of different ranks and they explained that the whole of the country was waiting on our victory.’

The day did not begin auspiciously, as Spartak were caught in a traffic-jam, causing the kick-off to be delayed. Twice in the first half they took the lead, only for the Basques to level but, after Shylovskyi had converted a controversial fifty-seventh-minute penalty, they ran away with it, Vladimir Stepanov completing a hat-trick in a 6-2 win. Nikolai Starostin later insisted his brother’s performance in an unfamiliar role had been ‘brilliant’, although the newspapers and the goalkeeper, Anatoly Akimov, disagreed, pointing out that Langara had dominated him in the air and scored one of the Basque goals.

That defeat proved an aberration. The Basques went on to beat Dynamo Kyiv, Dinamo Tbilisi and a team representing Georgia, prompting a furious piece in

Pravda

. Under the demanding headline ‘Soviet Players should become Invincible’, it laid down what had become obvious: ‘The performances of Basque Country in the USSR showed that our best teams are far from high quality… The deficiencies of Soviet football are particularly intolerable as there are no young people like ours in other countries, young people embraced by the care, attention and love of the party and government.’

Amid the bombast, there was some sense. ‘It is clear,’ the piece went on, ‘that improving the quality of the Soviet teams depends directly on matches against serious opponents. The matches against the Basques have been highly beneficial to our players (long passes, playing on the flanks, heading the ball).’

Four days later, the Basques rather proved

Pravda

’s point by completing the Soviet leg of their tour with a 6-1 victory over a Minsk XI. The lessons of the Basques, though, were not forgotten. It took time for the calls for increased involvement in international sport to be heeded, but it had been recognised that the W-M offered a number of intriguing possibilities.

The man who seized upon them most eagerly was Boris Arkadiev. Already highly regarded, he gradually established himself as the first great Soviet theorist of football. His 1946 book,

Tactics of Football

, was for years regarded as a bible for coaches across Eastern Europe.

Born in St Petersburg in 1899, Arkadiev moved to Moscow after the Revolution, where, alongside a respectable playing career, he taught fencing at the Mikhail Frunze Military Academy. It was fencing, he later explained, with its emphasis on parry-riposte, that convinced him of the value of counter-attacking. Having led Metallurg Moscow, one of the capital’s smaller clubs, to third in the inaugural Supreme League in 1936, Arkadiev took charge of Dinamo Moscow, who had won that first title. There, his restless mind and fertile imagination - not to mention his habit of taking his players on tours of art galleries before big games - soon gained him a reputation for eccentric brilliance. His first season brought the league and cup double, but he had to rethink his tactics as the lessons of the Basques revolutionised Soviet football.

‘After the Basque tour, all the leading Soviet teams started to reorganise in the spirit of the new system,’ Arkadiev wrote. ‘Torpedo moved ahead of their opponents in that respect and, having the advantage in tactics, had a great first half of the season in 1938 and by 1939 all of our teams were playing with the new system.’ The effect on Dinamo was baleful, as they slipped to fifth in 1938, and a lowly ninth the year after. With Lavrenty Beria, the notorious head of the KGB and the patron of the club, desperate for success, drastic action was required.

Others might have gone back to basics, but not Arkadiev: he took things further. He was convinced that the key was less the players he had than the way they were arranged, and so, in February 1940, at a pre-season training camp in the Black Sea resort of Gagry, he took the unprecedented step of spending a two-hour session teaching nothing but tactics. His aim, he said, was a refined variant of the W-M. ‘With the third-back, lots of our and foreign clubs employed so-called roaming players in attack,’ Arkadiev explained. ‘This creative searching didn’t go a long way, but it turned out to be a beginning of a radical

perestroika

in our football tactics. To be absolutely honest, some players started to roam for reasons that had nothing to do with tactics. Sometimes it was simply because he had great strength, speed or stamina that drew him out of his territorial area, and once he had left his home, he began to roam around the field. So you had four players [of the five forwards] who would hold an orthodox position and move to and fro in their channels, and then suddenly you would have one player who would start to disrupt their standard movements by running diagonally or left to right. That made it difficult for the defending team to follow him, and the other forwards benefited because they had a free team-mate to whom they could pass.’

The season began badly, with draws against Krylya Sovetov Moscow and Traktor Stalingrad and defeat at Dinamo Tbilisi, but Arkadiev didn’t waver. The day after the defeat in Tbilisi, he gathered his players together, sat them down and made them write a report on their own performance and that of their team-mates. The air cleared, the players seemed suddenly to grasp Arkadiev’s intentions. On 4 June, playing a rapid, close-passing style, Dinamo beat Dynamo Kyiv 8-5. They went on to win the return in Ukraine 7-0, and then, in the August, they hammered the defending champions Spartak 5-1. Their final seven games of the season brought seven wins, with twenty-six goals scored and just three conceded. ‘Our players worked to move from a schematic W-M, to breathe the Russian soul into the English invention, to add our neglect of dogma,’ Arkadiev said. ‘We confused the opposition, leaving them without weaponry with our sudden movements. Our left-winger, Sergei Ilyin, scored most of his goals from the centre-forward position, our right-winger, Mikhail Semichastny, from inside-left and our centre-forward, Sergei Soloviov, from the f lanks.’

The newspapers hailed the ‘organised disorder’, while opponents sought ways of combating it. The most common solution was to impose strict man-to-man marking, to which Arkadiev responded by having his players interchange positions even more frequently. ‘With the transition of the defensive line from a zonal game to marking specific opponents,’ he wrote, ‘it became tactically logical to have all the attackers and even the midfielders roaming, while having all the defenders switch to a mobile system, following their opponents according to where they went.’