Invisible Romans (25 page)

Authors: Robert C. Knapp

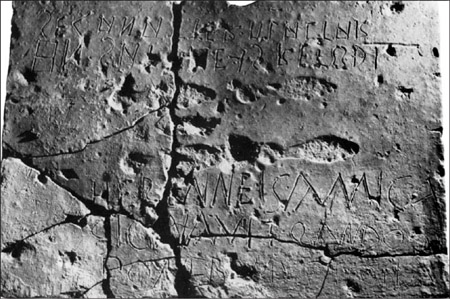

12. Slaves at work. Here two women slaves making roof tiles left imprints of their shod feet, and their names scratched into the yet soft clay. The scratches read (in Oscan) ‘Delftri, the slave of Herrenneis Sattis, signed this with her foot’; and (in Latin) ‘Amica, the slave of Herreneis, signed this, while we were setting out the tile to dry’

More serious were overt acts against the master’s interests. Theft was a constant possibility. There is ample evidence from the documents from Egypt that slaves were not trusted, and often earned that distrust. Mistresses as well as masters and overseers had to assume that slaves would steal. Food was particularly tempting:

Slaves are accused of having greedy mouths and bellies. And this is nothing astonishing. He who often starves, craves satiety. And obviously, anyone would prefer to take care of his hunger with delicacies, rather than with plain bread. So we should forgive if a slave goes for food he is normally denied. (Salvian,

The Governance of God

4.3.13–18)

Theft was endemic, whether to supply a real want, such as food, material to sell or trade to increase one’s

peculium,

or just to show defiance of the master.

Property damage was a form of theft, for it deprived the master of his possessions. Carelessness could always be pretended, and sabotaging equipment was a good way to avoid work, at least for a time. Failing to serve conscientiously was another way of retaliating – if the slave didn’t get caught:

Who then is the faithful and wise servant, whom the master has put in charge of the servants in his household to give them their food at the proper time? It will be good for that servant whose master finds him doing so when he returns. I tell you the truth, he will put him in charge of all his possessions. (Matthew 24:45–7)

So far so good – the faithful servant. However:

… suppose that servant is wicked and says to himself, ‘My master is staying away a long time,’ and he then begins to beat his fellow servants and to eat and drink with drunkards. The master of that servant will come on a day when he does not expect him and at an hour he is not aware of. He will cut him to pieces and … there will be weeping and gnashing of teeth. (Matthew 24:48–51)

It would be a rare but sweet revenge for a slave to do as Callistus did: His master had sold him as a worthless slave; his new owner made him a doorman, responsible for controlling entrance to his mansion. When his old master sought entrance, he turned him away, in turn, as unworthy (Seneca,

Letters

47).

Often, slaves were tempted to harm. In Egypt they are attested as showing disrespect to masters, shouting at them and otherwise insulting them. They are even seen participating in assaults and physical violence in the streets. Such was the extent of this behavior that a life for a slave owner could carry some risk on a regular basis. Actual murder of masters was probably rare, although, living among slaves, the elite were always potentially the target of extreme violence and there were enough actual examples to keep the possibility fixed in their minds. Besides various instances given in elite literature, an inscription from Mainz tells a story of slave revenge:

Jucundus, freedman of Marcus Terentius, a cattleman, lies here. Passerby, whoever you might be, stop and read. See how I complain to no avail, undeservedly taken from life. I was not able to live more than 30 years. A slave tore life from me and then cast himself headlong into the water below. The River Main took from that man what he had taken from his master. Jucundus’ patron erected this monument. (

CIL

13.7070 =

ILS

8511, Mainz, Germany)

From Clunia (Peñalba de Castro) in Spain comes another:

Atia Turellia, daughter of Gaius Turellius, age 27, was slain by a slave. Gaius Turellius and Valeria [erected this monument] … (

AE

1992.1037)

Violence against masters on a grand scale did not occur; slave rebellions practically cease before the empire, although escaped slaves provided a continuous feed for outlawry, which itself sometimes amounted almost to rebellion. Classic revolt conditions did not exist, however: the slave population was not heavily male, recently imported into slavery, or greatly more numerous than the free population. Nor were there proximate places to escape to even if there were rebellion. It is unlikely that slaves thought much about this ultimate violence.

They might, however, consider violence against themselves. From comparative material it is safe to assume that suicide was an accepted avenue of escape from the horrors of slavery. Slave suicides are mentioned in legal materials, and apparently one part of a standard description of a slave for sale included a statement of whether he had ever tried to commit suicide. Just above I have given the case of the slave who murdered his master, then threw himself into a river. But beyond this, there are surprisingly few examples of slaves committing suicide, although it is instructive that Lucius in

The Golden Ass

thinks of suicide as a way out of his plight – even if he never follows through.

What slaves did think about and do in large numbers – and this is clear from the dream interpretation and fortune-telling evidence noted above – was escape by running away. The main cause was abuse; the main constraint consideration of family and social ties that would need to be left behind. In

The Life of Aesop

there are constant references to running away as a logical act by a slave to escape a beating or other abuse, whether at the hands of the master or a fellow slave. Egyptian material documents the frequency of runaways and the worry this act caused masters. Epigraphy leaves us with the rather pathetic measure masters sometimes took to thwart running away: a slave collar. These collars were inscribed with such things as:

I am a slave of my master Scholasticus, an important official. Hold me so that I don’t escape from the mansion called Pulverata. (

AE

1892.68, Rome)

And:

Seize me because I have fled and bring me back to my master, the highly estimable Cethegus in the Livian market, third region of the city of Rome. (

CIL

6.41335, Rome)

And:

I am Asellus, slave of Praeiectus, an aide of the prefect of the grain supply. I have gone outside the walls. Seize me because I have run away. Bring me back to the place called ‘At the Flower,’ next to the barbers. (

CIL

15.7172 =

ILS

8727, Vellitri)

The

Carmen Astrologicum

of Dorotheus of Sidon has all the appearance of being used by slaves planning to or actually running away. The chart castings relating to their situation are eloquent: the runaway will ‘travel far away’ or ‘stay close by’; he ‘sticks to the street and does not stray and is not confused so that he arrives in his place which he wishes’; he ‘sheds blood in the place which he comes to so that because of this he will be seized by force so that he might be sent back to his master’; he ‘has caused suspicion and committed a ruse so that because of this he has fallen in chains’; ‘the runaway has lost the goods which he stole when he ran away, he wandered away from them, and the runaway will be seized and sent back to his master, and misery and chains will reach him in this running away of his.’ In six castings the runaway escapes successfully; in eight he is caught – perhaps in the house of a powerful person and retrieved only with great difficulty by the master, or returned but forgiven by his master, as seems to be the scenario desired by Paul in his letter to Onesimus’ master. On the run, life may be hard or even disastrous for the runaway: he could die in his flight, perhaps by burning or by the knife, or at the hands of men, or by an animal, or a building falling on him and killing him, or drowning in a flood, or suicide, or having his hands and feet cut off, or being strangled or crucified or burned alive, or drowning at sea. These predictions in sum cover just about anything that could happen to a runaway and are vivid evidence of many a slave’s focus on taking the radical step of escape from a master.

Once away, as the astrologer indicates, a slave might escape detection. One way to insure this was to have recourse to magic. Among the magic papyri is one that states that if a runaway carries three specified

Homeric verses inscribed on a small sheet of iron, ‘he will never be found.’ On a more practical level, because most would look and speak like the population they were running to, there would be no obvious way to identify a runaway. If challenged, how would anyone know a man was not free, unless a master or someone with a clear physical description appeared to accuse him of being a runaway? If they lacked the standard documentation of freedom, a person could only be proved to be ‘free’ or ‘slave’ by such things as distinguishing features, friends’ witness, and their own evidence. So, too, documents from Egypt include authorizations to seek out and punish runaways, while Pliny the Younger tells of detecting slaves who had sneaked into the Roman army – many others presumably did this undetected (Pliny,

Letters

10.29–30).

While on the run, a slave might take shelter with friends or former slaves of the household, take on work as a hired laborer, try to (illegally) join the army, become a robber, attach himself to a landowner as a tenant, or do just about anything a poor free person could in society. He might have a very hard life, and he might eventually be recaptured. But the harping of the elite literature on runaways; the detailed indications of intense interest in running away which the fortune-telling literature reveals; and the practical ease with which a runaway could melt into the population combine to show that running away was a very live choice for a slave in hard circumstances.

I have so far looked at the slave voice with regard to those who control their lives, whether slave (e.g. a foreman) or a free master, and have seen that voice in the material related to runaways. Next I turn to slaves voicing their fears that they will be sold away. Some few slaves might view being sold as a positive thing, a way to escape a bad master, but for most it was a thing to be dreaded: conditions, while they might be better with a different master, might also well be worse. But more than concern for their own well-being, the specter of sale meant the potential disruption of close, positive, supportive ties within the slave’s community.

Marriage, sex, and family

The closest ties were those of family. Although in law slaves could not marry – someone who had no ‘personhood’ could not be legally joined

to another – in fact they routinely developed long-term relationships. Indeed, a look at the evidence from inscriptions noting slave unions shows how hard it is to distinguish them from free unions in terminology or formulas. From time to time the mate is called a

contubernalis,

a ‘tentmate,’ the conventional term used to describe a partner in a slave union:

To the Netherworld Gods. Anna, slave of Quintus Aulus, lived 19 years. With no warning at all sudden death snatched her away in the flower of her youth. This is dedicated to the best mate (

contubernalis). (AE

1976.173, Cosenza)

To the Underworld Gods. Hermes Callippianius set this up to Terentina, slave of Claudius Secundus, who lived 22 years, 3 months. She was the dearest, most dutiful, most deserving mate. (

CIL

6.27152, Rome)

However, traditional words for ‘spouse,’

uxor

and

coniunx,

appear more frequently than does

contubernalis:

To the Netherworld Gods. Mercurius her fellow slave set this up to his well-deserving wife (

coniunx),

Fortunata. (

AE

1973.110, Rome)

This is set up to Primus, slave of Herennius Verus by Hilarica, his wife (

uxor

). (

CIL

3.11660, Wolfsberg, Austria)

And these words even appear in legal texts, clear evidence that they were accepted as descriptors of slave unions. Evidently, slaves could be thought of as ‘married’ by both slaves and free, whatever their juridical condition technically. Sometimes these unions were encouraged by the masters, as Varro advises: ‘Make the overseers more eager in their work by giving out rewards, and see to it that they can accumulate personal savings, and that each has a female fellow slave, so they can bear children together’ (

On Agriculture

1.17.5). Other times, the slaves themselves initiated the unions without specific encouragement. These could be fraught, and certainly sex was not restricted to such unions.