Invisible Romans (43 page)

Authors: Robert C. Knapp

Why even among the gladiators I observe that those who are not utterly bestial, but Greeks, when about to enter the arena, though many costly viands are set before them, find greater pleasure at the moment in recommending their women to the care of their friends and setting free their slaves than in gratifying their belly. (Plutarch,

Customs,

‘A Pleasant Life Impossible’ 1099B/Delacy and Einarson)

At the last feast, as part of the pageantry and advertising, the public was allowed in to watch and mingle. The last meal of (soon to be) St. Perpetua, before she was to be executed as a criminal (criminals also shared this

cena libera),

illustrates this:

The day before the games it was customary to feast at a last meal, which they called the ‘unrestricted dinner.’ But Perpetua and Saturnus made this into a Christian Last Supper feast (

agape),

not a ‘last meal.’ And with the same steadfastness, they taunted the people standing around, threatening the judgment of God, bearing witness to the good fortune that was their suffering, ridiculing the curiosity of those pushing and shoving about them. And Saturnus said, ‘Is tomorrow not enough for you? Why are you so eager to look on those you hate? Are we friends today, enemies on the morrow? Take a good look at our faces, so you can recognize us on that day!’ Thunderstruck, all then departed – and not a few believed. (

Passion of Saints Perpetua and Felicity

17)

The public could thus vicariously participate in the pageant by tossing comments to the gladiators and generally engaging in a personal way with the upcoming event. Presumably if autographs had been part of the culture, they would have had miniature swords or clay helmets signed as souvenirs.

And so the gladiator’s career would generate passionate enthusiasm and recognition that he excelled in manliness among fellow men. Gladiators themselves reveled in this effect. Their epitaphs record such sentiments as ‘great shouts roared through the audience when I was victor’; ‘I was a favorite of the stadium throng’ (Robert, nos. 55 and 124). One Pompeiian gladiator even took as an ‘arena name’ Celadus, which is derived from the Greek word for ‘clamor.’ Augustine has a vivid account of how the arena seized hold of a young man named Alypius:

Not wishing to lay aside the worldly career set down for himself by his parents, he had gone ahead of me to Rome in order to study law. And there he was utterly swept away by an unbelievable passion for the gladiatorial games. For despite the fact that he was opposed to – even detested – such things, a fatal meeting with friends and fellow students – he met them by chance returning from his midday meal – changed everything. With friendly urging they brought him, strongly objecting and resisting, into the amphitheater, seat of the savage and deadly games. He said to them, ‘Although you drag my body into this place, do you think you’ll be able to turn my spirit and eyes to that spectacle? I am here – but I’m

not

here. And so I’ll get the best of both you

and

the games.’ When they heard this, they hastened all the more to coerce him along with them, eager to find out if in any way he was able to do as he said. When they got there and had gotten settled into their seats, everything seethed with unimaginable raw emotion. Alypius, eyes tightly closed, forbade himself to get involved in such monstrous evil. Oh, if only he had closed his ears as well! For at a critical moment in the fight, when a huge clamor wildly pulsated from the whole crowd, overwhelmed by curiosity and thinking himself ready to condemn and control whatever might be happening, even gazing on it, he opened his eyes. That was it. His spirit was stabbed with a more severe wound than the gladiator whom he longed to see received in his body, and he fell, more miserable than the fighter whose fall had brought the roaring crowd to its feet … As soon as he saw the blood, he drank in at once the fierce cruelty of it all. He did

not

turn away, but rather stared, rooted to the spot, imbibing the madness, and didn’t even realize what was happening. He took wicked delight in the contests; he was drunk with the gory excess. Now he was not the person who had entered the amphitheater; now he was one of the mob he had joined, a true fellow fan of those by whom he had been dragged in. He looked on; he shouted; he threw himself into it completely – and he left consumed by that insanity that would impel him to return again not only with those friends who had first brought him, but even without them, inducing others to come along. (

Confessions

6.8)

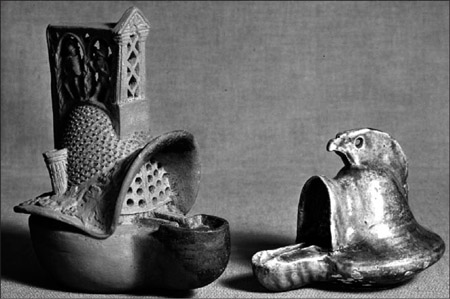

30. Souvenirs. Gladiator memorabilia was very popular. It ranged from vastly expensive engraved glass beakers to common lamps with battle scenes embossed. Here are two more laborate lamps in the shape of gladiators’ helmets.

The enthusiasm of the crowd could easily spill over into disorder. Elite literature is sprinkled with examples of the crowd shouting insulting things at the emperor from the protection (which sometimes proved illusionary) of the mob. Indeed, the assembling of ordinary people in such venues as the amphitheater or theater provided perhaps their best opportunities to confront their leaders. Beyond local ramifications, gladiatorial contests could become proxies for local competitions, jealousies, and rivalries. The most famous example of this is the rivalry of Nucerians and Pompeiians from two small cities in Campania, Italy. The historian Tacitus describes the riot this rivalry brought about in the course of gladiatorial games attended by spectators from both towns:

About this same time a terrible mayhem arose from a really inconsequential beginning. It all happened at gladiatorial games given by Livineius Regulus, a local Pompeiian bigwig recently expelled from the Roman senate. Locals from the neighboring towns of Nuceria and Pompeii were hurling insults at each other the way small-town rivals often do. Words became stones; then swords were drawn. The Pompeiians got the best of it – they were the home crowd, after all. As a result, many wounded Nucerians were carried up to Rome, and many wept over the death of a parent or child. The emperor referred the matter to the senate, the senate to the consuls. They, in turn, put the question again in the senate’s lap. That body decreed a ten-year moratorium on gladiatorial events at Pompeii, and the clubs, which had been formed illegally, were disbanded. Livineius and the others who had fomented the riot were exiled. (

Annals

14.17)

Quite amazingly, a fresco painting from Pompeii survives that illustrates this very riot. Some citizens fight inside the arena, while outside Nucerians and Pompeiians are attacking each other with clubs and fists. Elsewhere a graffito adds immediacy to the painting: ‘Campanians, by this victory you’ve been destroyed with the Nucerians’ (

CIL

4.1293). Other graffiti express similar thoughts, probably unrelated to this specific event: ‘Bad luck to the people of Nuceria!’ (

CIL

4.1329); ‘Good luck to all the people of Puteoli, good luck to the people of Nuceria, and down with the people of Pompeii!’ (

CIL

4.2183). Passions clearly ran high, and not just regarding who was going to win a particular gladiatorial combat.

In addition to the adoration of the crowd, a gladiator was likely to gain access to unlimited sexual partners, for the adoration, not to say lust of women for gladiators – virtually naked, muscular, shining with

virtus,

notoriously available – was common knowledge. The graffiti of Pompeii reveal the pull of sexual conquest that went along with victory in the arena. The successful gladiator Celadus boasts in a couple of scribbles, ‘Celadus, one of Octavius’ Thracian gladiators, fought and won three times. The girls swoon over him!’ (

CIL

4.4342 =

ILS

5142a) and ‘Celadus the Thracian gladiator. Girls think he’s magnificent!’ (

CIL

4.4345 =

ILS

5142b).

But it would be a mistake to assume that every gladiator became a crowd favorite. For every man who won the heart of the crowd, there were many others who slogged along in the profession, trying to stay alive and not especially admired. Petronius in his

Satyricon

records a fictional critique of such fighters. After praising a future game that will feature free, not slave, gladiators, and ones who won’t shy away from fighting, Echion adds:

After all, what has Norbanus [a wealthy Pompeiian] ever done for us? He put on a two-bit gladiatorial show, decrepit men who would have fallen down if you breathed hard on them. I’ve seen better

beast

fighters

than those guys. He killed off some caricatures of mounted fighters – those castrated cocks, one a feckless spawn, yet another bandylegged, and in the third match a man as good as dead, already hacked up badly. There was, I’ll admit, a

thrax

who had some gumption, but even he fought strictly by the rules. In short, their manager flogged each and every one after the matches – and the crowd hollered for him to beat them more! They were little better than runaway slaves! (

Satyricon

46)

Not everyone became a star.

Beyond the arena, gladiators were the objects of popular culture. There were lamps and fancy glass jugs featuring gladiatorial motifs; Trimalchio had expensive cups illustrated with scenes from an apparently epic contest between two very famous gladiators, Petraites and Hermeros, and he planned to have further scenes from Petraites’ victories carved on his tomb monument (

Satyricon

52, 71); and children dressed up and played as gladiators. With all the hype and cultural popularity, it is small wonder that once in the service, a gladiator yearned to fight:

But among the gladiators in the emperor’s service there are some who complain that they are not put up against anyone or set in single combat, and they pray to God and approach their managers begging to go out to single combat in the arena. (Epictetus,

Discourses

1.29.37)

It was in fighting that the gladiator gained and maintained his luscious fame.

But despite the draw, a gladiator also knew that he was betting everything. One speaks from a Cretan grave: ‘The prize was not a palm branch; we fought for our life’ (Robert, no. 66). And things did not always work out so well. A gravestone tells it all:

I, who was brimful of confidence in the stadium, now you see me a corpse, wayfarer, a

retiarius

from Tarsus, a member of the second squad, Melanippos [by name]. No longer do I hear the sound of the beaten-bronze trumpet, nor do I rouse the din of flutes during onesided contests. They say that Herakles completed 12 labors; but I, having completed the same [number], met my end at the thirteenth. Thallos and Zoe made this for Melanippos as a memorial at their own expense. (Robert, no. 298/Horsley)

The scanty evidence from epigraphy indicates that perhaps 20 percent of participants were killed; if all fought in duels, then one in ten duels would end in a death, although other scholars have put the fatality rate at 5 percent, or one in twenty matches. On either calculus, fighting in more than ten duels would be pushing the odds severely. In all likelihood most gladiators were killed in their first or second fights (George Ville makes an arresting comparison to World War I aerial combat), while survivors went on to win many more. In exceptional cases every fight would end in a death, but this was an expensive result, and a games’ sponsor who lost a lot of valuable property thought it worth boasting about:

Here at Minturnae [Italy] over a four-day period Publius Baebius Iustus, Town Mayor, in honor of his high office put up 11 fighting pairs of first-rate gladiators from Campania; a man was slain in each of the combats. (

CIL

10.6012 =

ILS

5062)

But once a gladiator hit his stride, his career could be long. There are inscriptions boasting of between fifty and a hundred-plus victories. One example of a gladiator with a long career can be found in the epitaph of Flamma (meaning ‘Flame’), a

secutor,

i.e. a heavily armed man who normally fought against a

retiarius,

a man with sword and net:

Flamma the

secutor

lived thirty years and fought thirty-four times. He won outright twenty-one times; fought to a draw nine times; was honorably defeated four times. He was from Syria. Delicatus [‘Delightful’] made this to his well-deserving fellow-at-arms. (

ILS

5113, Palermo)

Flamma therefore fought for around thirteen years (about age seventeen to thirty), and so on average 2.5 times a year. This is more frequent than most. Of the fifteen gladiators whose records are known, most fought less than twice a year; perhaps a few gladiators fought more

than three times a year – although for some, fighting was much more frequent, as a graffito recording a summer’s games demonstrates: