Iran: Empire of the Mind (16 page)

Drunk with Love: The Poets and the Sufis,

the Turks and the Mongols

From the very beginning the grand theme of Persian poetry is love. But it is a whole teeming continent of love—sexual love, divine love, homoerotic love, unrequited love, hopeless love and hopeful love; love aspiring to oblivion, love aspiring to union and love as solace and resignation. Often it may be two or more of these at the same time, ambiguously hinted at through metaphor and intermingled. And often love may not be mentioned at all, but be massively present nonetheless through other metaphors, notably through another great theme—wine.

It is possible that the Persian poetry of this period inherited ideas and patterns from a lost tradition of Sassanid court poetry—love poetry and heroic poetry—just as Ferdowsi’s

Shahnameh

emerged from a known tradition of stories about the kings of Persia. But most of the verse forms of metre and rhyme, along with the immediate precedents of themes of love, derive from previous Arabic poetic traditions, reflecting the exchange of linguistic and other cultural materials between Iranians and Arabs in the years after the conquest. There are fragments of poetry known from earlier, and the first more substantial verses from known poets come from the period of the Taherids, but the first great figure was a poet at the Samanid court—Rudaki:

Del sir nagardadat ze bidadgari

Cheshm ab nagardadat cho dar man nagari

In torfe ke dusttar ze janat daram

Ba anke ze sad hezar doshman batari

Your heart never has its fill of cruelty

Your eyes do not soften with tears when you look at me

It is strange that I love you more than my own soul,

Because you are worse than a hundred thousand enemies.

19

Rudaki (who died around 940), along with other poets like Shahid Balkhi and Daqiqi Tusi, benefited from the deliberate Persianising policy of the Samanid court. The Samanids gave the Persian poets their patronage, and encouraged the use of Persian rather than Arabic at court, in literature and generally. Abolqasem Ferdowsi (c. 935-c. 1020) was less fortunate. He was born in the period of Samanid rule but later came under the rule of the Ghaznavids, a dynasty of Turkic origin, when the Samanid regime crumbled. His

Shahnameh

(which continued and completed a project begun for the Samanids by Daqiqi) can be seen as the logical fulfilment of Samanid cultural policy—avoiding Arabic words, eulogising the pre-Islamic Persian kings and going beyond a non-Islamic position to an explicitly pro-Mazdaean one. Some of the concluding lines of the

Shahnameh

, speaking as if from just before the defeat at Qadesiyya and the coming of Islam, echo the earliest Mazdaean inscriptions of Darius at Bisitun—shocking in an eleventh-century Islamic context (the

minbar

is the raised platform, rather like a church pulpit, from which prayers are led in the mosque):

They’ll set the minbar level with the throne,

And name their children Omar and Osman.

Then will our heavy labours come to ruin.

O, from this height a long descent begins

…

Then men will break their compact with the Truth

And crookedness and Lies will be held dear.

20

No surprise then that his great work, when finished, got a less than enthusiastic welcome from the ruling Ghaznavid prince, whose views were more orthodox. Many of the stories that have been passed down through the centuries about the lives of the poets are unreliable, but some of them may at least reflect some aspects of real events. One story about the

Shahnameh

says that the Ghaznavid sultan, having expected a shorter work of different character, sent only a small reward to Ferdowsi in return. The poet, disgusted, split the money between his local wine seller and a bath attendant. The sultan eventually, when read a particularly brilliant passage from the

Shahnameh

, realised its greatness and sent Ferdowsi a

generous gift, but too late; as the pack-animals bearing Ferdowsi’s treasure entered his town through one gate, his body was carried out for burial through another.

The great themes of the

Shahnameh

are the exploits of proud heroes on horseback with lance and bow, their conflicts of loyalty between their consciences and their kings, their affairs with feisty women, slim as cypresses and radiant as the moon, and royal courts full of music and feasting; a life full of fighting and feasting—

razm o bazm

. It is not difficult to read into it the nostalgia of a class of bureaucrats and scholars, descended from the small gentry landowners (the dehqans) who had provided the proud cavalry of the Sassanid armies, reduced from the sword to the pen, now watching Arabs and Turks play the great games of war and politics.

Tahamtan chinin pasokh avord baz

Ke hastam ze Kavus Key bi niaz

Mara takht zin bashad o taj targ

Qaba joshan o del nahade bemarg

The brave Rostam replied to them in turn,

‘I have no need of Kay Kavus.

This saddle is my throne, this helm my crown.

My robe is chainmail; my heart’s prepared for deat

’

21

The

Shahnameh

has had a significance in Persian culture comparable to that of Shakespeare in English or the Lutheran Bible in German, only perhaps more so—it has been a central text in education and in many homes, second only to Hafez and the Qor’an. It has helped to fix and unify the language, to supply models of morality and conduct, and to uphold a sense of Iranian identity reaching back beyond the Islamic conquest, that might otherwise have faded with the Sassanids.

The poetry of the

Shahnameh

, and its themes of heroism on horseback, love, loyalty and betrayal, has much in common with the romances of Medieval Europe, and it is thought-provoking that it first attained fame a few decades before the First Crusade brought an increased level of contact between western Europe and the lands at the eastern end of the Mediterranean. We have already seen how ideas were transferred from east to west without it being possible later to trace their precise route

(there is a stronger theory that the troubadour tradition, and thus the immensely fruitful medieval European trope of courtly love, originated at least in part with the Sufis of Arab Spain

22

). But it may just be a case of parallel development.

The Ghaznavids did not reverse the Samanid pattern of patronage, and continued to encourage poets writing in Persian; but the later poets were less strict about linguistic purity and more content to use commonplace Arabic loan-words. Further west the Buyid dynasty, originating among Shi‘a Muslims in Tabarestan, had expanded to absorb Mesopotamia and take Baghdad (in 945), ending the independent rule of the Abbasid caliphs and ruling from then on in their name. But the great literary revival continued to be centred in the east.

Naser-e Khosraw was born near Balkh in 1003, and is believed to have written perhaps 30,000 lines of verse in his lifetime, of which about 11,000 have survived. He was brought up as a Shi‘a, made the pilgrimage to Mecca in 1050 and later became an Ismaili before returning to Badakhshan to write. Most of his poetry is philosophical and religious –

Know yourself; for if you know yourself

You will also know the difference between good and evil.

First become intimate with your own inner being,

Then commander of the whole company.

When you know yourself, you know everything;

When you know that, you have escaped from all evil

…

Be wakeful for once: how long have you been sleeping?

Look at yourself: you are something wonderful enough.

23

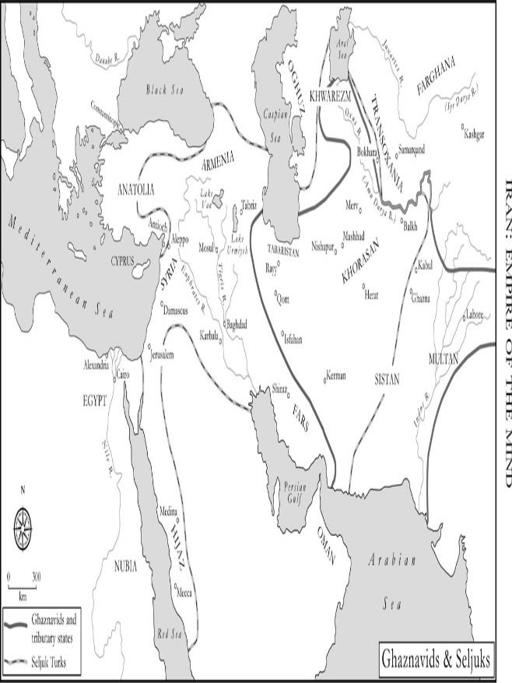

For many years the Abbasid caliphs and the other dynasties had employed Turkish mercenaries, taken as slaves from Central Asia, to fight their wars and police their territories. Turks had in turn become important in the politics of the empire, and on occasion had threatened to take control—the Ghaznavids had succeeded in doing so in the eastern part of the empire. But in the middle of the eleventh century a confederation of Turkic tribes under the leadership of the Seljuk Turks went further. They defeated the Ghaznavids in the north-east, broke into the heartlands of the empire and took Baghdad, before fighting their way further west and

in 1071, defeating the Byzantines and occupying most of the interior of Asia Minor. Centuries of contact with the Abbasid regime and its successors had Islamised the Turks and had made them relatively assimilable. The second Seljuk sultan, Alp Arslan, had a Persian, Hasan Tusi Nizam ol-Mulk (1018-1092), as his chief vizier, and before long the dynasty was ruling according to the Persianate Abbasid model like the others before it. Nizam ol-Mulk wrote a book of guidance for Alp Arslan’s successor called the

Siyasat-Nameh

(The Book of Government), which along with the slightly earlier

Qabus-nameh

, for centuries was the model for the Mirror of Princes genre of literature, also influencing European versions of the same kind of thing, down to the time of Machiavelli and his

Principe

.

Nizam ol-Mulk was a friend of Omar Khayyam (c.1048-c.1124/1129) and there are some famous stories of dubious veracity about the friendship;

24

but it is probably true that when Nizam ol-Mulk became vizier he gave some financial help to Omar Khayyam, and possibly some protection too. Among Iranians it is commonplace to say that Omar Khayyam was a more distinguished mathematician and astronomer than a poet. To assess the validity of this is like trying to compare apples with billiard balls. He did work on Euclidian geometry, cubic equations, binomial expansion and quadratic equations that experts in mathematics regard as influential and important. He developed a new calendar for the Seljuk sultan, based on highly accurate observations of the sun, that was at least as accurate as the Gregorian calendar ordained in Europe by the Catholic church in the sixteenth century

25

; and it seems he was probably the first to demonstrate the theory that the nightly progression of the constellations through the sky was due to the earth spinning round its axis, rather than the movement of the skies around a fixed earth as had been assumed previously.

Omar Khayyam’s dry scepticism in his poetry makes his voice unique among the other Persian poets, but also reflects a self-confidence drawn perhaps from his pre-eminent position in his other studies, and his knowledge that in them he had surpassed what was known before. His name is famous in the west through the translations of Edward Fitzgerald, and were taken by his readers to represent a spirit of eat, drink and be merry hedonism, which is not quite right. They are free translations, and

Fitzgerald’s nineteenth-century idiom (fine though his verses are), with its dashes and exclamation marks, ohs and ahs, to a degree traduces the sober force of the originals:

‘How sweet is mortal Sovranty!’—think some:

Others—‘How blest the Paradise to come!’

Ah, take the cash in hand and waive the Rest;

Oh, the brave Music of a distant Drum!

(Fitzgerald)

Guyand kasan behesht ba hur khosh ast

Man miguyam ke ab-e angur khosh ast

In naqd begir o dast az an nesye bedar

K’avaz-e dohol shenidan az dur khosh ast

(Original)

It is said that paradise, with its houris, is well.

I say, the juice of the grape is well.

Take this cash and let go that credit

Because hearing the sound of the drums, from afar, is well.

26

Translating poetry is notoriously difficult, and some would say that it is a vain endeavour entirely. For example, the word ‘khosh’ has a wide range of related meanings and is found in a series of compound words in Persian so that, with those, it takes up several pages in any dictionary. It means delicious, delightful, sweet, happy, cheerful, pleasant, good and prosperous: one can see different shades of these meanings in each of the three lines in which it appears in this poem. The form of the poem is the quatrain, or

ruba’i

—the plural is

rubaiyat.

Other Persian verse forms include the

ghazal

, the

masnavi

and the

qasida

. Most of Omar Khayyam’s surviving poetry is in the ruba’i form, but there has been much doubt as to which of the thousand or more rubaiyat attributed to him were actually his work. It seems likely that the poems of others, that were of a sceptical or irreligious tendency and might have attracted disapproval, were attributed to him in order to have the grace accorded his great name. At the same time, it may be that he set down doubts in his poems that were only part of his thinking about the deity. But one can read in his poems a rugged humanism in the face of the harsh realities of life, and an impatience

with easy, consoling answers, that anticipates existentialism. A recognition of the complexity of existence, and the intractability of its problems, and a principled acceptance. His philosophical writing largely revolved around questions of free will, determinism, existence and essence.

27