Is There a Nutmeg in the House? (43 page)

Read Is There a Nutmeg in the House? Online

Authors: Elizabeth David,Jill Norman

Tags: #Cooking, #Courses & Dishes, #General

While the first batch is baking, roll out the trimmings, cut out and bake more sablés, repeating the process until all the dough is used up. Yield should be about 3 dozen.

Unpublished, late 1970s

Hunt the Ice Cream

First editions are fascinating to collectors of every category of book, no doubt with good reasons. When it comes to cookery books, however, it is a fearful mistake to pay large sums for first editions and neglect later ones, and this applies particularly to works which have had a long life. In my view – and I don’t expect booksellers to agree with me – first editions of such books as Robert May’s

Accomplisht Cook

of 1660, Hannah Glasse’s

Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy

1747, and Mrs Rundell’s

New System of Domestic Cookery

1806 wouldn’t be anything like as interesting to serious students of cookery as later ones, in which the authors themselves have made revisions, corrected errors, added new recipes, brought cooking methods up to date, and incorporated recently introduced ingredients.

It is of course – or would be – agreeable to own first editions and to be in a position to make comparisons, study an author’s development and changing tastes over a period of time, establish at what moment certain types of recipe started appearing in print, and discover from them small landmarks in social history; but

first editions

can

be studied in the great libraries, and furthermore in later and less rare editions the evidence of change is often contained in a new Author’s Preface, Introduction or publisher’s puff, and is there for anyone who reads their books attentively.

To take

The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy

, no cookery book of the eighteenth century provides a better example of the importance of studying successive editions and of the traps lying in wait for anyone who assumes that the earliest editions are more interesting than later ones.

Between 1747 and 1765 nine editions of the Glasse book were published and after the author’s death in 1770, many more, pirated by different publishers. The earliest edition I have, or have seen, is the fourth, dated 1751. It was in this edition that the full page engraved advertisement for ‘Hannah Glasse, habit maker to Her Royal Highness the Princess of Wales’ appeared. It was the first time that the book was openly acknowledged as Mrs Glasse’s, her signature, H. Glasse, being printed in facsimile under the title

The Art of Cookery

on page one of the text, although the title page proper still carries the earlier legend: ‘By a lady’. It was also in 1751 that a four-page Appendix appeared, apparently for the first time.

Among the handful of 1751 additions in the Appendix were the well-known directions for dressing a turtle the West India way, and a recipe for raspberry ice cream. This is not quite the earliest so far found in an English cookery book,

1

but it precedes the apricot ice cream given by Elizabeth Raffald in

The Experienced English Housekeeper

of 1769 by eighteen years. It is unfortunate that Mr Eric Quayle, author of a recently published picture book (

Old Cookery Books, An Illustrated History

) asserts categorically that Mrs Raffald’s was the first ice cream recipe published in an English cookery book. How did he come to miss the Glasse recipe? For that matter how did the O.E.D. miss it?

It is of course difficult to win with Hannah Glasse. Anyone who consulted only very late editions of

The Art of Cookery

might well get the impression that Mrs Glasse had plagiarised Mrs Raffald, for in a posthumous edition of 1784 Mrs Glasse’s own raspberry ice cream was replaced with Mrs Raffald’s apricot one. Interestingly, in her

Compleat Confectioner

, undated but judged by Oxford to be

c

.1760,

2

Mrs Glasse elaborated on her original directions, but did not, I think, borrow or lift from

anyone. Not that I am for a moment suggesting that Mrs Glasse was innocent of plagiarism. In

The Art of Cookery

she made very free with the work of her predecessors, as did nearly all other cookery book compilers of her period, and for that matter of any other. In the instance of the ice cream, however, and also of the

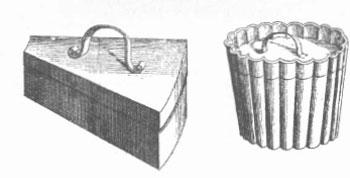

The lower part of the frontispiece of Emy’s

L’Art de bien faire les glaces d’office

1768. (The upper part, too faint to reproduce, shows two ethereal beings reclining on a cloud and awaiting the ice cream which the cherubs are confecting for them.)

addition to the story of the Reform Club’s genie, the man who also volunteered to organise the almost non-existent cooking for the troops in the Crimea, who attempted to relieve the Irish during the famine, who could as easily superintend a 238-cover civic banquet in York in honour of the Prince Consort as a Christmas dinner for 22,000 of London’s poor – once more the whole ox roasted by gas – or betake himself to Castle Howard to show off his dexterity with his famous little Magic Stove. Cooking on the supper table in the ballroom (the Queen was staying), Soyer produced, or appeared to produce, his well-known

oeufs au miroir

at the rate of six every two minutes.

many recipes in the lengthy Appendix mentioned above, it is plain to me that she is reporting at first hand, and sometimes with an original and charming turn of phrase.

In the matter of containers for the freezing of her ices, Mrs Glasse used two pewter ‘basons’, the inner one with a close cover. In this the prepared cream was put. It was then set in the larger one and surrounded with ice and a handful of salt. After three quarters of an hour she uncovered the inner container, stirred the cream, covered it again and left it to freeze for a further half hour. After that, ‘turn it into your plate’. That was her 1751 method. In the

Compleat Confectioner

she repeats it, but adds that ‘your basons should be three cornered, that four colours may lie in one plate; one colour should be yellow, another green, another red, and a fourth white’. In both recipes she tells her readers that the basons are made at the pewterer’s, adding the further note that ‘some make their ice cream in tin pans, and mix three pennyworth of saltpetre and two pennyworth of roach allum, both beat fine, with the ice, as also three pennyworth of bay salt; lay it around the pan as above, cover it with a coarse cloth, and let it stand two hours’.

The mention of saltpetre is interesting. It was used to help reduce the temperature, but what the function of the roach or rock alum was I don’t know. No doubt someone conversant with physics and chemistry can enlighten me. As to the basons of the original recipe, it occurs to me that by basons Hannah Glasse meant the tall pewter cylinders such as were in use in France for freezing ice creams. They are depicted in the frontispiece of Emy’s

L’Art de bien faire les glaces d’office

, 1768, and I remember years ago seeing a splendid collection of them in the pousada at Elvas in Portugal. The ‘three-cornered basons’ are a little more difficult. I think that very likely they were deep wedge-shaped boxes or moulds with handled covers. When turned out on to a dish four differently coloured ices would form a complete circle, like a cake. An engraving of one such box appears on Plate 6 of Gilliers’ famous

Le Cannameliste Français

, first (1751) edition, and is shown on the previous page with one other mould for the freezing of cream which flanks it on the Plate.

Those interested by the way, in knowing more of Mrs Glasse, her origins and career, should consult the original detective work done by Madeleine Hope Dodds, a Northumbrian local historian. The curious story was first told by her in an article called

The Rival

Cooks

, published in 1938 in

Archeologia Aeliana

, the journal of the Northumberland Archaeological Society. A summary of this, written by Mr Norman Brampton, was published in the Wine and Food Society

Quarterly

, no. 114, summer 1962, and a good account, interestingly illustrated and further researched, is given by Anne Willan in her

Great Cooks and Their Recipes. From Taillevent to Escoffier

, a correctly-documented book, although her publishers have made it difficult, owing to fancy production, to read the recipes Miss Willan quotes. Sources of the illustrations also take some ferreting out, but at least they are given. Mr Quayle, on the other hand, does caption most of his illustrations with their sources. There are, however, omissions, and these, together with many preposterous historical blunders other than the one concerning the ice cream, reduce the credibility of the book almost to vanishing point. Why for example are we not told the provenance of the semi-caricature captioned ‘The redoubtable Mrs Hannah Glasse’? Authors who claim to write history and fail to cite sources can hardly expect to be taken seriously.

References

1

. See Nathaniel Bailey’s

Dictionarium domesticum

, 1736, cited by C. Anne Wilson in her admirable book

Food and Drink in Britain

, Constable 1973 and Penguin Books 1976.

2

. The B.M. Catalogue puts it at 1770. The second edition is dated 1772.

THREE EARLY ENGLISH ICE CREAM RECIPES

I. FROM NATHANIEL BAILEY’S

DICTIONARIUM DOMESTICUM

, 1736.

To make

ICE CREAM

Fill tin icing pots with any sorts of cream you please, either plain or sweetened, or you may fruit it; shut the pots very close; you must allow three pounds of ice to a pot, breaking the ice very small; laying some great pieces at the bottom and top.

Lay some straw in the bottom of a pail, then lay in the ice, putting in amongst it a pound of bay salt; set in your pots of cream, and lay the ice and salt between every pot, so that they may not touch; but the ice must be lai’d round them on every side; and let a good quantity be laid on top; cover the pail with straw, set it in a cellar, where no sun or light comes, and it will be frozen in four hours time; but you may let it stand longer; and take it out just as you use it; if you hold it in your hand and it will slip out.

If you would freeze any sort of fruit, as cherries, currants, raspberries, strawberries, etc. fill the tin pots with the fruit; but as hollow as you can; put lemonade to them, made with spring water, and lemon juice sweetened; put enough in the pots to make the fruit hang together and set them in ice as you do the cream.

2.

FROM HANNAH GLASSE

’

S

ART OF COOKERY MADE PLAIN AND EASY

, 4

TH EDITION

, 1751.

To make

ICE CREAM

Take two Pewter Basons, one larger than the other; the inward one must have a close Cover, into which you are to put your Cream, and mix it with Raspberries, or whatever you like best, to give it a Flavour and a Colour. Sweeten it to your Palate; then cover it close, and set it into the larger Bason. Fill it with Ice, and a Handful of Salt; let it stand in this Ice three Quarters of an Hour, then uncover it, and stir the Cream well together; cover it close again, and let it stand half an Hour longer, after that turn it into your Plate. These things are made at the Pewterers.

Note

Hannah Glasse,

The Art of Cookery Made Plain and Easy

, the Fourth Edition, with Additions 1751, p. 332. Although announced as Additions on the title page, the section of seven extra recipes is actually headed

Appendix

. In the 1758, sixth edition, they were re-titled

Additions

, and confusingly sub-titled

As Printed in the Fifth Edition

. This time the seven recipes had increased to ten, so presumably the three extra ones had appeared in the fifth, 1755 edition, which I have not seen. The sixth edition also has a new

Appendix

running to 45 pages.