Island of Shame: The Secret History of the U.S. Military Base on Diego Garcia

Read Island of Shame: The Secret History of the U.S. Military Base on Diego Garcia Online

Authors: David Vine

Tags: #Social Science, #Anthropology, #Cultural, #Political Science, #Human Rights, #History, #General

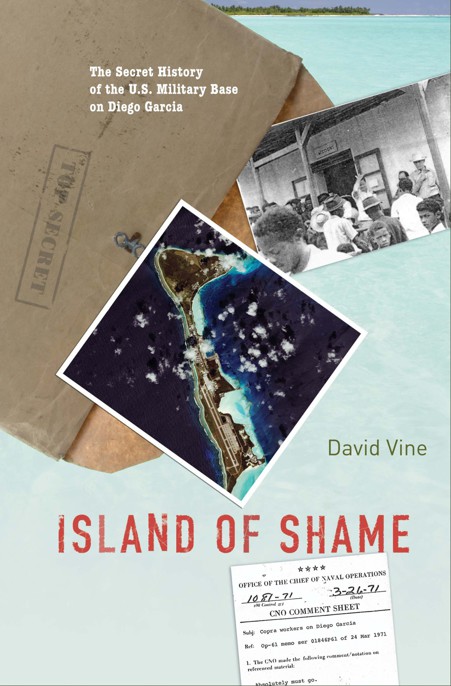

ISLAND OF SHAME

ISLAND OF

SHAME

The Secret History of

the U.S. Military Base

on Diego Garcia

With a new afterword by the author

David Vine

Copyright © 2009 by Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 6 Oxford Street,

Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TW

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

Fourth printing, and first paperback printing, 2011

Paperback ISBN 978-0-691-14983-7

THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS HAS CATALOGED THE CLOTH EDITION OF THIS BOOK AS FOLLOWS

Vine, David, 1974–

Island of shame : the secret history of the U.S. military base on Diego Garcia / David Vine.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-691-13869-5 (hbk. : alk. paper) 1. United States. Naval Communications Station, Diego Garcia—History. 2. Military bases, American—British Indian Ocean Territory—Diego Garcia. 3. Chagossians—History. 4. Population transfers—Chagossians. 5. Refugees—Mauritius. 6. Refugees—British Indian Ocean Territory. 7. British Indian Ocean Territory—History. 8. Diego Garcia (British Indian Ocean Territory)—History.

I. Title.

VA68.D53V66 2008

355.70969’7—dc22 2008027868

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available This book has been composed in Adobe Garamond The author will donate all royalties from the sale of this book to the Chagossians.

Printed on acid-free paper. ∞

Printed in the United States of America

5 7 9 10 8 6 4

“No person shall be . . . deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process; nor shall private property be taken for public use, without just compensation.”

—Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution, 1791

“No one shall be subjected to arbitrary arrest, detention or exile. . . . No one shall be subjected to arbitrary interference with his privacy, family [or] home. . . . No one shall be arbitrarily deprived of his property. . . . Everyone has the right to freedom of movement and residence within the borders of each State.”

—Articles 9, 12, 17, 13, Universal Declaration

of Human Rights, 1948

“We, the inhabitants of Chagos Islands—Diego Garcia, Peros Banhos, Salomon—have been uprooted from those islands. . . . Our ancestors were slaves on those islands, but we know that we are the heirs of those islands. Although we were poor there, we were not dying of hunger. We were living free.”

—Petition to the governments of the United Kingdom

and the United States, 1975

CONTENTS

List of Illustrations and Tables

1. The Ilois, The Islanders

2. The Bases of Empire

3. The Strategic Island Concept and a Changing of the Imperial Guard

4. “Exclusive Control”

5. “Maintaining the Fiction”

6. “Absolutely Must Go”

7. “On the Rack”

8.

Derasine

: The Impoverishment of Expulsion

9. Death and Double Discrimination

12. The Right to Return and a Humanpolitik

Afterword to the Paperback Edition

ILLUSTRATIONS AND TABLES

ILLUSTRATIONS

0.1 World Map

0.2 Diego Garcia

1.1 The Chagos Archipelago

1.2 East Point, Diego Garcia, 1968

1.3 Schoolchildren in Chagos, 1964

2.1 The Global U.S. Military Base Network

6.1 Closing Diego Garcia, January 24, 1971

6.2 CNO Zumwalt’s comment sheet

7.1 The BIOT’s

Nordvær

7.2 United States Government officials involved in Diego Garcia

7.3 “Aunt Rita”

8.1 Rita David and box

9.1 “Try It and You’re Stuck”

11.1 Chagos Refugees Group office

11.2 Aurélie Talate and Olivier Bancoult

TABLES

1.1 Chagos Population, 1826

3.1 “Strategic Island Concept”: Information on Potential Sites

FOREWORD BY MICHAEL TIGAR

I write this foreword with pride and humility. Pride, because I was present when David Vine first had the inspiration to take on the task of research and writing that led to the book you are holding. The year was 2001. I was part of a team of lawyers from Great Britain, Mauritius, and the United States who were seeking justice for the Chagossian people. I had just returned from visiting the camps in which they are housed in Mauritius. It seemed to me that if we were to explain the Chagossian story of betrayal, struggle, and hope, it would be essential to understand their history, culture, and present condition. A series of telephone conversations led me to Dr. Shirley Lindenbaum, a cultural anthropologist of international renown. She suggested that David Vine would be a perfect candidate for this job. David, Dr. Lindenbaum, and two of my colleagues met in New York, and David launched the work that was to consume him for seven years. From this minor role in the beginning, I take pride.

As for humility: This book and the work it represents have succeeded beyond my greatest hopes. David Vine is one of those rare scholars who combines all the qualities that one must have to write in this field. We are witnessing, on a global scale, the subordination and forced disappearance of hundreds of indigenous populations. We read of the more sensational and violent episodes of these conflicts, but so many others escape our notice. An indigenous population is not “entitled,” under what passes for international law, to automatic protection from dislocation. Its status as a cohesive group must first be established. When it is proposed to impose upon it, one must ask what aspects of its culture and history are to be seen as essential or important.

In this process of determining what is just and what is not, the people about whom one is speaking need a voice. They need the help of someone who will understand their lives as deeply as possible and portray their situation honestly and in terms that will withstand debate. David Vine has, in this book, shown us that he combines the scholar’s rigor with the student’s sympathetic understanding.

I have been a lawyer and law teacher for more than forty years. Given the nature of complex litigation, and particularly human rights litigation, we need to call upon experts in various fields to help us present claims for justice. We know that our adversaries will bring their own experts, and

each expert’s conclusions will be subject to testing in the crucible of cross-examination. From the beginning, David Vine has identified and followed all the principles of academic rigor that make this study credible as well as persuasive.

David Vine’s scholarship is also informed by his systematic and disciplined worldview. He sees the Chagossian people in the context of global struggle. He provides us with a context that makes their story compelling—and relevant. Choices about people’s fates and futures are not simply matters of preference, as to which one view is as good as another. Today, we understand that verifiable arguments about the human condition can, and must, be based on close observation of the social forces that people confront as they seek the basic rights that the international community has now defined as essential. David Vine has made an indispensable contribution to this process.

Figure 0.1 World Map, with Diego Garcia and Chagos Archipelago near center; Mauritius and Seychelles insets; the United States of America including all officially claimed territories.

ABBREVIATIONS AND INITIALISMS

CIA | Central Intelligence Agency |

CNO | Chief of Naval Operations |

CRG | Chagos Refugees Group |

DOD | Department of Defense |

FOIA | Freedom of Information Act |

GOM | Government of Mauritius |

HMG | Her Majesty’s Government [Government of the United Kingdom] |

IMF | International Monetary Fund |

ISA | Office of International Security Affairs, Department of Defense |

JCS | Joint Chiefs of Staff |

NASA | National Aeronautics and Space Administration |

NSC | National Security Council |

Rs | Rupees [currency of Mauritius and the Seychelles] |

USG | U.S. Government |

USO | United Service Organization |

A NOTE TO THE READER

Quotations that appear in this book without citation come from interviews and conversations conducted during my research. Translations from French, Mauritian Kreol, and Seselwa (Seychelles Kreol) are my own. The names and some basic identifying features of Chagossians in the book (other than members of the Bancoult family and representatives of the Chagos Refugees Group) have been changed in accordance with anonymity agreements made during the research.

ISLAND OF SHAME

Rita felt like she’d been sliced open and all the blood spilled from her body.

“What happened to you? What happened to you?” her children cried as they came running to her side.

“What happened?” her husband inquired.

“Did someone attack you?” they asked.

“I heard everything they said,” Rita recounted, “but my voice couldn’t open my mouth to say what happened.” For an hour she said nothing, her heart swollen with emotion.

Finally she blurted out: “We will never again return to our home! Our home has been closed!” As Rita told me almost forty years later, the man said to her: “Your island has been sold. You will never go there again.”

Marie Rita Elysée Bancoult is one of the people of the Chagos Archipelago, a group of about 64 small coral islands near the isolated center of the Indian Ocean, halfway between Africa and Indonesia, 1,000 miles south of the nearest continental landmass, India. Known as Chagossians, none live in Chagos today. Most live 1,200 miles away on the western Indian Ocean islands of Mauritius and the Seychelles. Like others, 80-year-old Rita lives far from Mauritius’s renowned tourist beaches and luxury hotels. Rita, or Aunt Rita as she is known, lives in one of the island’s poorest neighborhoods, known for its industrial plants and brothels, in a small aging three-room house made of concrete block.

Rita and other Chagossians cannot return to their homeland because between 1968 and 1973, in a plot carefully hidden from the world, the United States and Great Britain exiled all 1,500–2,000 islanders to create a major U.S. military base on the Chagossians’ island Diego Garcia. Initially, government agents told those like Rita who were away seeking medical treatment or vacationing in Mauritius that their islands had been closed and they could not go home. Next, British officials began restricting supplies to the islands and more Chagossians left as food and medicines dwindled. Finally, on the orders of the U.S. military, U.K. officials forced the remaining islanders to board overcrowded cargo ships and left them on the docks in Mauritius and the Seychelles. Just before the last deportations, British agents and U.S. troops on Diego Garcia herded the Chagossians’ pet dogs into sealed sheds and gassed and burned them in front of their traumatized owners awaiting deportation.