Isolation Play (Dev and Lee) (64 page)

Read Isolation Play (Dev and Lee) Online

Authors: Kyell Gold

Not for us, though, hopefully. And I did find out something very helpful, that Ivan doesn’t care that Mikhail has a gay son. So Mikhail’s concerns about ‘the guys at the auto shop’ are at least not universally warranted. Though Ivan doesn’t seem the sort to voice his own opinions strongly, certainly not around the more dominant Mikhail.

I lean back against the wall and close my eyes. I can’t help but think that whatever Mikhail does to me after this is going to be a doozy. Dislocate my thumb? I’ll embarrass you in the tabloids. Get me fired? I’ll throw you against a toolbox and put you in the hospital. How does he top that one? It’s like some kind of domestic Fibonacci series of violence, and where I should’ve stopped it, I continued it without meaning to.

Which leads me to the scary thought, the one I’ve been avoiding. What if...

No. He’s fine. The EMT said so. He should know. Think about something else.

So I think about football. I run through the Dragons’ current woes in my head and my list of prospects. I think about the kids I’ve looked at, and I think about the big bear Victor King. If I get out of this, I tell myself, I’m going to look him up and write him again. I’m going to arrange for Dev to see him in the off-season and talk to him.

I wonder what his parents are like, if they’re the kind who’d be open to it if only he’d confide in them, or if they’re the fundie type who would kick him out. Probably the dad is much more into the macho image, all about a man being the strong guy who knocks down his enemies, keeps his wife aproned and pregnant, tosses back beers at the bar, and has belching contests. Then again, I shouldn’t stereotype based on species. I hate it when people assume I’m trying to put one over on them just because I’m a fox. It makes it so much harder to put one over on them.

But I wasn’t trying to put one over on Dev’s father. I was honestly just trying to get him to understand. My big plan, the idea I was sure was going to work, failed. He didn’t care who fucks whom in our relationship. Doesn’t care that his son’s the one on top. I thought for sure that that’d do it. Hell, I pretty much opened right up to him, and he just blew it off.

Though he didn’t really come off as extremely bigoted. He never called me a sodomite, never said I was going to hell. He never called me a faggot, not to my face. He just said I’d turned Dev against him. So he’s one of those “it’s okay, but not in my family” guys. I guess, like Ivan said.

If that’s the case, though, why did he keep talking to me? Why didn’t he just throw me out? He kept the conversation going. He felt strongly enough to fight about it. About what? What more does he want? I feel like I’m close to something. Maybe there was something he said during our first visit? I can’t remember anything properly except his paw closing around mine, the snap of the ligament. I flex my wrist and rub the splint on my thumb.

He ain’t violent

, Ivan said. Ha. Well, now he’s in the hospital.

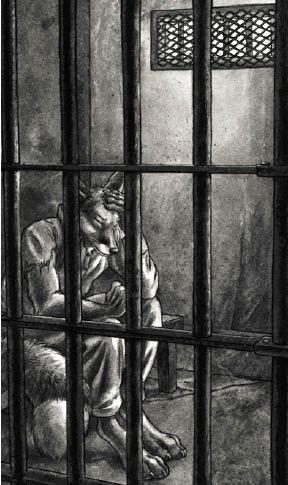

He’s in the hospital, and I’m in jail. The presence of the bars makes me feel guilty the longer I stare at them. I didn’t do anything wrong, I tell myself. Maybe the grab on the sleeve that started it, but I didn’t try to throw him into a toolbox. I want to tell Dev all of it, to make sure he hears it from me, but I can’t disturb him for two more days.

Though I could leave him a voicemail. He’ll be in practice all day with his phone off. I’ll just say I had a talk with his father and he didn’t kill me, and I’ll call him back after the game to tell him more. He’ll suspect it’s not good news, but I’ll tell him not to call me back, and he’ll have to listen to that because I won’t answer the phone if he calls again.

So when Chaz comes back with lunch, I call in that favor he offered. He brings the phone over to the cell and pushes it through with the food. Dev’s voicemail picks up, of course, and I leave the message just the way I rehearsed it. “I’m fine,” I say. “Win the game, I’ll call you Sunday night.” It won’t work. He’ll know right away something’s wrong. But he’ll know I’m not hurt.

Chaz grins. He got himself a big pile of vegetables between two buns, which he enjoys at the bare desk outside the cell while I dig into the fast-food fried chicken sandwich he got me. “So, you a huge Firebirds fan?”

“

Duh,” I say. “But ’til Monday, I worked for the Dragons. College scout.”

That gets him interested, and for most of the afternoon, we talk about football, only taking breaks when the chief pokes his head in to ask why Chaz isn’t at his desk. “He’s a risk,” Chaz protests. “I’m just keepin’ an eye on him.”

“

Reason we got bars is so you don’t hafta,” the chief grumbles. But he doesn’t order Chaz back to his desk. “At least get yer paperwork done if yer gonna be yakkin’ it up in here all day.”

At the end of the day, Chaz offers to run out again to get me dinner. “We got a sandwich machine here, but that’s kinda...” He sticks his tongue out.

“

You don’t have to,” I say.

“

You don’t have to be sittin’ in the cell,” he says, “But y’are.”

I perk my ears. “Coq au vin?”

He rolls his eyes. “McGrilled Chicken it is.”

I make a show of licking my lips. He snorts, and waves good-bye.

A day of sitting on the wooden bench leaves my butt hurting worse than the day after the no-lube night. So I sit cross-legged on the floor and lean up against the wall. The station is quiet except for a series of snores from the adjacent cell.

About half an hour after Chaz leaves, there’s an argument outside. I pad to the bars and stick my ear between them. Through the snores next door, I hear a familiar vulpine voice, and with a warm flush, I recognize my father. The door’s partly open, so when I cup my ears, I can hear some of the words. The chief says things like, “City folk,” and my dad says, “due process,” but the chief successfully defends his home turf, and in the end nobody comes in to release me.

Chaz does come in with a McD’s bag, twenty minutes later. He tells me the chief is dead set on holding me on suspicion until morning. Father apparently said something about getting a lawyer and the chief said when he was ordered to release me, he would. Chaz doesn’t think that’ll be anytime soon. “Didn’t have no lawyer with him.”

“

So I’m gonna sleep here.”

“

Looks that way. Sorry. Lemme get you that blanket.”

“

Do you have two?”

He does. I fold them onto the bench and sit on them, because I’m not cold yet. When he leaves, the jail grows very quiet. It leaves me alone with my thoughts, even though the officer on night duty, a short skunk, pokes her muzzle in from time to time.

The isolation, the bars of the jail, the stark white lighting all make me feel small and alone. Father really came for me, though, and that’s something. He’ll get me out in the morning, I think, but then I wonder, what if he doesn’t? What if Mikhail presses charges and I’m convicted of assault and battery? What a great story that’d make for Hal. When I wrote my story in my head, I was the noble suffering figure, beset by injustice on all sides, fighting the good fight. And yet, here I am, having put someone in the hospital because I couldn’t leave well enough alone.

I know I’d promised to be less pushy, and I tried. But when it’s the right thing to do, when I can’t think of any other way to make things better, what else can I do? It’s not like I gave in to impulse and ran down the block to yell at Mikhail. I called his wife. I thought out what I was going to say. The alternative, leaving things alone, would just have prolonged Dev’s and my suffering—and his parents’ suffering, for that matter.

His father’s suffering. I push that image away again, but my imagination keeps bringing it back. It wasn’t my fault, not entirely, but I can’t evade responsibility for it, for any of it.

Dev would be frantic just to know his father’s in the hospital. His father, who’s generally been an asshole, and worse. Whereas my father, whom I’ve gone out of my way not to talk to, drove all the way up here to get me out of jail. He threatened a wolverine with a lawyer. I press fingers to my eyes and think about what an asshole I’ve been to him in the past. At least I’ve already started to make it up to him. I can do more. I will do more. Whatever he’s going through with Mother is their business. It’s not really about me, no matter how it started. But I can be there for him to talk to.

I’ll see him at Thanksgiving. I should’ve gone last year, no matter what Mother said or did.

If you’d come last year

...

And Dev’s father: If he were strong, he would be here.

I didn’t go to Thanksgiving because my mother made me feel uncomfortable. Dev didn’t talk to his father because he was afraid of what he might say. They put up the barriers, but we allowed them to stand.

Dev and I have a lot more in common than you might think from looking at us. Or meeting us. We think the same way about things, we like each other’s company, and we have grown to trust each other. We know that each of us is looking out for the other as much as himself. That’s what makes a family, at the core of it, that closeness and trust. When people’s worlds get too far apart, their connections can’t hold. Everyone likes to pretend that families are forever, but divorces happen. Kids get disowned, parents get put into retirement homes and forgotten. Brothers fight, sisters fight, grandparents, aunts, uncles.

Do some people stay together longer than they should, because of some blood relationship? Sure. But then there’s my father. If we were just friends, he’d never have come all the way up here to get me out of jail. And there’s Dev’s father. However misguided his methods, I believe he really does love his son, so fiercely that he would hurt both of them in the short term to do what he thinks is best for the family in the long term.

Can’t say the same for my parents. But I have Dev. We’re as close as if we were married, and if this last month hasn’t proven that, then nothing will. I don’t seem to be able to keep other people in my life, besides him. But that’s okay, because I’ve never needed a lot of other people. As long as I have my tiger. As long as I didn’t completely fuck things up today.

Well, hey, if I did, then maybe my father and I can move into an apartment together. It’d be like a sitcom. “Farrel and Son. Join a fox and his son as they try to set up a new life. The father’s recently divorced his intolerant wife over their gay son, who’s on parole for putting his ex-boyfriend’s father into a coma.” I can hear the laugh track as I bring home a flamboyant drag queen and my father, thinking he’s a girl, falls for “her.”

Life would be a lot easier if it were a sitcom. No matter what the situation, you could be sure that in half an hour, it’d be over. Every week you’d start back in the same place. You could do whatever you wanted and you’d never have to worry about change. Occasionally, we’d learn a meaningful lesson. If this were one of those episodes, I’d tell Father at the end of it how much I’ve learned to appreciate him in the last half hour. Then next week, we’d be back to normal.

But the one I really want to talk to isn’t Father. While Mikhail’s in the hospital, we’re all suspended, waiting, and Dev has no reason to hate me, no reason not to talk to me. Just as well my cell phone’s sitting there in the desk. I don’t think I’d be able to resist the temptation to call if I had it on me. I miss my tiger with an ache like broken ribs, a pressure in my chest that brings my fingers to my eyes again.

I won’t cry, not here. I’m strong. Whatever I’ve done, I’ll live with it. And, I reflect, it could easily have been me lying in the hospital, though I doubt Mikhail would be in jail right now if it were. And then Dev would be equally crushed, wouldn’t he? Nothing his father said would help, if he would even say anything. Maybe he’d just let Dev hear about it on the news.

The image of that scene in my mind stirs thoughts. Dev and his father talking, arguing. I laugh silently; like anyone would care enough to televise my injury. Unless it was public knowledge that I was Dev’s boyfriend. That’d be funny, wouldn’t it? If Mikhail’s spiteful outing came back to haunt him?

Why did I have to hear about this on television?

I’m sure I wouldn’t appreciate the joke. At least it’d be worse than Dev coming out on television, right?

I stare at the ceiling, thinking harder about the things I’ve heard both my father and Dev’s say. Insight flickers and blossoms. The familiar temptation of believing I’ve figured things out returns, full force, and refuses to go away. It’s frustrating. What am I supposed to do about it

now

? As if I haven’t fucked things up enough. But if I was looking at things all wrong, if I have it right this time... My tail flicks. Do I trust myself to try again?