It Happened at the Fair (11 page)

Read It Happened at the Fair Online

Authors: Deeanne Gist

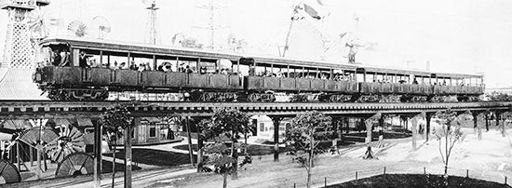

POSTAL CAR

“Full-size dummies took him back in time to the cowboy and mustang of the Pony Express.”

CHAPTER

9

Standing at the fair’s postal counter in the Government Building, Cullen waited as a clerk checked to see if he’d received any mail. The fair was due to open in thirty minutes, so no one else was about. He basked in the quiet. So different from Machinery Hall.

Every method of mail carrying, from an old stagecoach to the latest postal car, played out before him. Full-size dummies took him back in time to the cowboy and mustang of the Pony Express. A mountain carrier in snowshoes stood across from a bullet-riddled coach that had twice been captured by Indians. His favorite display, though, was the dog-sledge and team, so lifelike he expected to hear the dogs bark at any moment.

DOG SLEDGE IN WAX

The clerk returned, and a surge of pleasure shot through him when the man handed him a letter, not from Wanda, but from home. Finally. He tore it open, then flipped to the second page to see that Reverend Roebuck had penned it for his father. The more he read, though, the slower he walked, giving no notice to a giant globe of the United States, land grants from colonial times, or a procession of wax figures clad in army uniforms. He pushed out the south door and made his way to Machinery Hall by rote as he reread the letter.

Dad owed the Charlotte merchant two hundred dollars, which he couldn’t pay, so they’d refused to give him any more credit. Cullen let his hand fall for a minute. What was Dad thinking to spend three hundred on sending him to the fair when he owed two hundred to the merchant? What happened to that cushion he’d talked about?

Shaking out the letter, he picked up where he’d left off. Dad didn’t want him worrying. He’d gone to the bank and borrowed a thousand dollars. The only reason he was even saying anything was because Cullen had asked. Dad promised it was nothing to fret over.

Nothing to fret over? He borrowed a thousand dollars and didn’t want Cullen to fret over it? He rubbed his mouth. A thousand seemed awfully excessive. Still, it would pay off the merchant debt and leave them with eight hundred to go toward taxes, seed, mortgage, supplies, and expenses. Or it should have. But it hadn’t.

He turned to the next page. Dad had been required to pay some interest off first. Interest of four hundred dollars, in addition to the two hundred in principal.

Cullen frowned. The interest shouldn’t have been that high. Something wasn’t right. He’d write Reverend Roebuck and ask him to check on the interest rate. In the meanwhile, Dad still had four hundred dollars left. It wouldn’t be enough come the end of the year, though.

He sighed. Dad had always handled the money. He couldn’t read and write so well, but he was good at numbers. Besides, it was his farm. Since Dad had never brought up the subject of money, Cullen hadn’t felt all that comfortable asking. But just because he hadn’t asked didn’t mean he was unaware of the price of cotton or how many bales they’d produced. The number he hadn’t had was how much Dad spent. Evidently, quite a bit. Enough for him to need to borrow a thousand dollars.

He rubbed his eyes. If the cotton prices held and they had a good year, they should make four hundred—three hundred at the worst. And with the way the economy was going, he probably should count on the worst.

Tucking the letter back into the envelope, he climbed the steps of Machinery Hall. Dad’s four hundred and the harvest’s three hundred would leave them about three hundred short. Earning back the money Dad had spent on sending him to the fair was no longer just a goal, it was a necessity. He’d ask Mrs. Harvell one more time if she’d let him leave early and refund his money for the days he had left. But he didn’t have much hope of that happening. No one was parting with his money right now—not after the National Cordage Company had gone bankrupt the first week of the fair.

It might have been the company’s own fault for trying to corner the market, but the fact was, it had overspent, incurred huge debt, and used up all its cash to pay investors. Everyone was still waiting to see what the fallout would be, but whatever it was, it would be big and it would affect the whole country. No, Mrs. Harvell was a shrewd woman. She’d not be refunding anything.

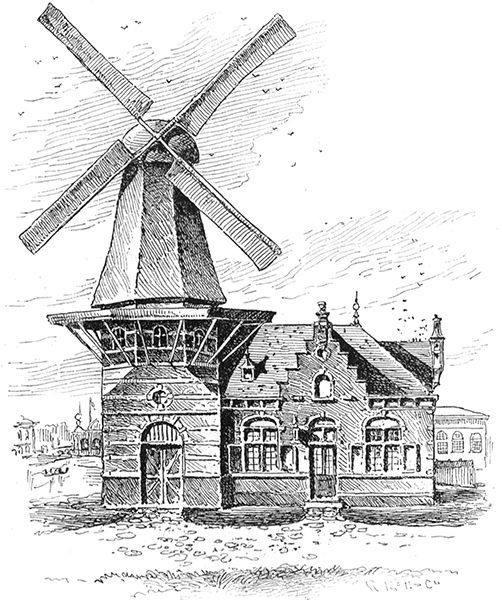

BLOOKER’S DUTCH COCOA COMPANY

“A Dutch maiden wearing wooden shoes and a gaudy dress curtseyed to Della.”

CHAPTER

10

Della had never taught an adult before, and certainly not a man. Knowing she’d need to establish a professional teacher-student relationship, she’d dressed in the most matronly suit she had. Beneath her coat she wore a somber black skirt and bolero. She felt sure it added at least four years to her twenty.

Weaving between the Machinery and Agricultural Buildings, a short, red-faced man pushed a rolling chair into her path. She quickly jumped aside, then followed its progress. In its seat was the man’s rather large and portly wife, with a young tot in her lap. Two little girls in their Sunday dresses sat on each armrest, holding tightly to their mother. A young boy, not quite old enough for school, sat on the mother’s feet, dangling his legs over the footrest.

Good heavens. They certainly were making the most of their forty-cents-an-hour chair rental.

Rousing herself, she continued down the pathway. A woman staggered out of the Agricultural Building, squinted into the light, and propped a hand on her waist. “Well, of all the confounded messes. Whoever planned this fair made it so whenever you come out of a building, you ain’t anywhere nearer anything in particular.”

Her husband pulled a Rand McNally map of the fair from his coat, and the two began to puzzle over it. Della could certainly sympathize. She’d become lost in the Court of Honor alone. No telling how many times she would turn herself around before the fair’s closing date.

Then she remembered Mr. McNamara would be with her much of that time. Perhaps he had a better sense of direction than she did.

Just past the obelisk, a crowd converged on a set of wooden stairs like sand in an hourglass, all heading for the elevated railroad that ran throughout the grounds. She skirted around them, then glanced up at the four-car train screeching to a halt and rattling the scaffolding supporting it.

ELEVATED ELECTRIC TRAIN

She paused for a closer look. No cloud of smoke, nor any of the familiar chug and belch of a steam engine.

She studied the crisscross of cables above it.

“Marvelous,” a man close by breathed.

And indeed it was marvelous. The train was powered by electricity.

Shaking her head, she hurried on, holding her breath so as not to smell the cattle, horses, swine, and sheep in the Livestock Exhibit and gave no pause for Germany’s outdoor exhibit. Blooker’s was straight ahead.

The clumsy old tower was a replica of a long-standing Holland windmill built at the beginning of the century. But instead of grinding meal, the giant blades now powered a chocolate grater. Just thinking about it made her mouth water.

BLOOKER’S DUTCH COCOA MILL

Pushing open the large wooden door, she waited a moment to let her eyes adjust. A rich chocolate aroma enveloped her, along with warmth from the cheery fire. She removed her gloves and unbuttoned her double-breasted jacket. Mr. McNamara had yet to see her.

His coat lay draped over an empty chair beside him. His hat rested on its seat. He conversed with a rosy-cheeked Dutch maiden wearing wooden shoes and a gaudy dress. With one hand she balanced a tray of cups of steaming cocoa. Her other hand rested on a cocked hip. Throwing back her head, she laughed at something he said.

Della zeroed in on her lips.

“I am named after my mudder. Trudel . . .”

Della couldn’t read her last name—something Dutch that started with a z and ended with a p.

“Strudel?” he asked.

Again the girl burst into giggles. “Nee, nee. Not Strudel, Trudel.”

Mr. McNamara smiled, putting into play his laugh lines and dimples. The girl was so captivated her tray began to tilt.

Reaching up, he steadied it.

“May I guide you to a table, miss?” A Dutch maiden dressed in the same manner as Trudel curtseyed to Della.