Italian All-in-One For Dummies (129 page)

Read Italian All-in-One For Dummies Online

Authors: Consumer Dummies

Ho visto una ragazza la cui bellezza mi ha colpito.

(

I saw a girl whose beauty struck me.

)

Abbiamo fatto una riunione il cui scopo non mi era chiaro.

(

We had a meeting whose purpose wasn't clear to me.

)

You need any other preposition before the relative pronoun, you can use indifferently

You need any other preposition before the relative pronoun, you can use indifferently

cui

or

il quale.

You add only the preposition to

cui: con cui

(

with whom/which

),

da cui

(

by whom/which

), or

su cui

(

on whom/which

). You add a combined article to

quale:

con il quale

(

with whom/which

),

dal quale

(

by whom/which

), or

sul quale

(

on whom/which

).

La persona sulla quale avevamo contato non ci può aiutare

or

La persona su cui avevamo contato non ci può aiutare

(

The person on whom we had counted can't help us

).

If you need a preposition with the relative pronoun (either

If you need a preposition with the relative pronoun (either

il quale

or

cui

), you may not skip it. However, with

cui

only, you may (but don't have to) skip the preposition

a

(

to

) or

per

(

for

) to indicate aim or purpose (not motion), and leave

cui

all by itself, as in

La faccenda cui ti riferisci è stata sistemata

(

The problem you're referring to has been solved

).

Following are some examples of relative pronouns at work combining two sentences:

Ho conosciuto un cantante famoso. Questo cantante famoso una volta ha vinto il Festivalbar.

(

I met a famous singer. This famous singer once won Festivalbar.

)

Ho conosciuto un cantante famoso che una volta ha vinto il Festivalbar.

(

I met a famous singer who once won the Festivalbar.

)

Compro caramelle ogni giorno. Ogni giorno compro caramelle alla liquirizia.

(

I buy candies every day. Every day I buy licorice candies.

)

Le caramelle che compro ogni giorno sono alla liquirizia.

(

The candies that I buy every day are licorice

.)

Vedo che ti piace dipingere. Dipingi soprattutto quadri astratti.

(

I [can] see that you like to paint. You especially paint abstract paintings.

)

I quadri che ti piace dipingere di più sono quelli astratti.

(

The paintings that you mostly prefer to paint are abstract paintings.

)

Roma è una città affascinante. Provengo da Roma.

(

Rome is a fascinating city. I come from Rome.

)

Roma, la città da cui provengo, è affascinante.

(

Rome, the city I come from, is fascinating.

)

Hai parlato di un problema col tuo capo. Ã un problema di stipendio?

(

You discussed a problem with your boss. Is it a salary-related problem?

)

Il problema di cui hai parlato col tuo capo è di stipendio?

(

Is the problem that you discussed with your boss salary-related?

)

Siamo partiti dall'aeroporto JFK di New York. Siamo tornati all'aeroporto JFK di New York.

(

We left from New York's JFK airport. We returned to New York's JFK airport.

)

Siamo tornati all'aeroporto JFK di New York, da cui eravamo partiti.

(

We returned to New York's JFK airport, from which we had left.

)

Si crede agli UFO. Si crede alle favole.

(

You can believe in UFOs. You can believe in fairy tales.

)

C'è chi crede agli UFO e alle favole.

(

There are some [people] who believe in UFOs and in fairy tales.

)

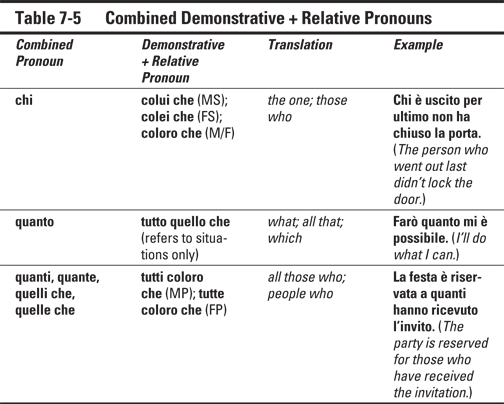

Economy of speech: Combined pronouns

In addition to relative pronouns, Italian has combined relative pronouns. A combined pronoun is a single word that conveys two meanings: a demonstrative word and a relative pronoun. For example, the pronoun

quanto

(

what; all that; which

) contains both the demonstrative

quello

(

that

),

tutto quello

(

all that

), and the relative pronoun

che

(

which

). For example,

Farò quanto mi è possibile

/

Farò tutto quello che mi è possibile

(

I'll do what I can

).

You can use the combined or non-combined form of the relative pronouns â it's your choice. The combined forms are very convenient, just as the pronoun

what

is in English.

If you use a non-combined form, you can see that each of the two components of the pronoun plays a different function. Consider this example:

Non faccio favori a coloro che non lo meritano

(

I don't do favors to those who don't deserve them

). With the demonstrative component

a coloro

(

to those

), you convey aim or purpose; in fact, you need the preposition

a

(

to

). The relative component

che

(

who

) is the subject of the relative clause. And because in this case the demonstrative

coloro

is plural, the verb of the relative clause is plural, too.

If you collapse the two components in a combined form, you're also collapsing the two grammatical functions. So, in keeping with the preceding example,

a coloro che

becomes

a chi

(

those who

): The pronoun takes the preposition

a

to convey aim or purpose, but it's a singular pronoun, so you need the verb in the singular in the relative clause, as in

Non faccio favori a chi non lo merita

(

I don't do favors to those who don't deserve them

).

Remember that the combined pronouns can convey

A direct object and a subject, as in

A direct object and a subject, as in

Lisa ringrazia chi le ha mandato i fiori/Lisa ringrazia coloro che le hanno mandato i fiori

(

Lisa thanks those who sent her flowers

) or

Lisa ringrazia colei/colui

che le ha mandato i fiori

(

Lisa thanks the person who sent her flowers

). (Given the context at your disposal, the pronoun

chi

can refer to all the persons mentioned.)

Two direct objects, as in

Two direct objects, as in

Invito quanti ne voglio

or

Invito tutti coloro che voglio

(

I'm inviting all those I want to invite

).

An indirect object and a subject, as in

An indirect object and a subject, as in

Siamo riconoscenti per quanto hanno fatto per noi

or

Siamo riconoscenti per quello che hanno fatto per noi

(

We're thankful for what they did for us

).

Table 7-5

presents the combined pronouns and their non-combined counterparts along with some examples.

Chapter 8

Asking and Answering Questions

In This Chapter

Seeing how basic questions are formed in Italian

Seeing how basic questions are formed in Italian

Asking open-ended questions

Asking open-ended questions

Figuring out how to answer complex questions

Figuring out how to answer complex questions

Giving a negative response to a question

Giving a negative response to a question

W

ho? What? When? Where? Why? How? These basic questions, and variations on them, allow you to get the information you need in any language. Knowing how to ask questions is essential in the Italian world (and beyond). Here are some simple questions that can be answered with

yes, no,

or

one or two words.

Vieni con noi?

(

Are you coming with us?

)

Sì.

(

Yes.

)

à già arrivata?

(

Has she already arrived?

)

No.

(

No.

)

Come stai?

(

How are you?

)

Bene, grazie.

(

Fine, thanks.

)

Chi parla?

(

Who's speaking?

)

Elisabetta.

(

Elizabeth.

)

But questions become more open-ended as you dig deeper and want more details and as you gain confidence and build your vocabulary. You also become more skilled at understanding and answering questions asked of you. This chapter assists you in asking and answering questions, which leads to conversation, discussion, even disagreement â all forms of your ultimate Âlinguistic goal: communication.

Looking at Ways of Asking Questions in Italian

“Curiouser and curiouser” is the language-learner's motto. To satisfy your curiosity and to understand both a different language and a different culture, you need to be able to ask questions. You have relatively easy ways to do this: You can change your tone (or pitch) of voice, you can add a word like

right?

to the end of a sentence, or you can move the subject from the beginning to the end of a sentence.

Adjusting your intonation

Language is musical, and nowhere do you hear that better than in crafting sentences to make a statement, to exclaim, or to ask a question.

With a statement, you keep your voice pretty level. For example:

With a statement, you keep your voice pretty level. For example:

Carlo parla italiano

(

Carlo speaks Italian

) has a level tone with a slight drop at the end. To make this statement into a question, you raise your tone (think of it as going up a couple of notes on the musical scale) on the next-to-last syllable and then drop back a note on the very last syllable:

Carlo parla ital /ia \no?

(

Does Carlo speak Italian?

) Listen to yourself ask that question in both English and Italian; you discover that you make this same tone change in English.

Another option is to leave the sentence as a statement but finish it off with words like

no?

non è vero?

or just

vero?

All translate, more or less, into

right?

or

isn't that so?

You can also say

ok?

or

va bene?

both of which mean

okay?

When you use these words, your intonation again goes up a note or two on the musical scale. Here are some examples:

Ho comprato i biglietti, va bene?

(

I've bought the tickets, okay?

)

Andiamo al cinema domani, no?

(

We're going to the movies tomorrow, aren't we?

)

Tuo padre lavora sempre a Milano, vero?

(

Your father still works in Milan, doesn't he?

)

Inverting the word order

Another way to turn a statement into a question is to move the subject from the beginning to the end of the sentence.

Carlo parla italiano

(

Carlo speaks Italian

) is a statement;

Parla italiano, Carlo?

(

Does Carlo speak Italian?

) is a question.

This technique works only if you have a stated subject. Here's another example:

Il gatto ha mangiato tutto il cibo.

(

The cat has eaten all the food.

)

Ha mangiato tutto il cibo, il gatto?

(

Has the cat eaten all the food?

)

Asking some common questions

The following standard questions will get you into the practice of asking about things. Some are more open-ended (like those that ask where something is) and may elicit a longer response than you can understand at first. You can anticipate an answer to a

where

question by using props â a street map, for example, allows someone to show you what they're talking about.

Come sta?

Come sta?

(

How are you?

[formal])

Come stai?

Come stai?

(

How are you?

[familiar])

Come va?

Come va?

(

How are things going?

)

Come si chiama?

Come si chiama?

(

What is your name?

[formal])

Come ti chiami?

Come ti chiami?

(

What is your name?

[familiar])