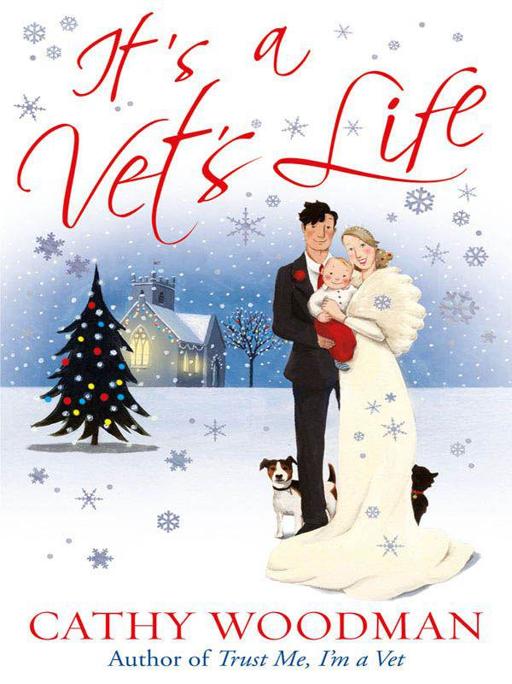

It's a Vet's Life:

Chapter One: Horses for Courses

Chapter Three: To Have and to Hold

Chapter Four: From this Day Forward

Chapter Eight: To Love and to Cherish

Chapter Ten: In Sickness and in Health

Chapter Eleven: Alas, Poor Harry

Chapter Thirteen: A Horse in the House

Chapter Fourteen: For Richer, for Poorer

Chapter Fifteen: Ten Weeks and Counting

Chapter Seventeen: All Creatures Great and Small

Chapter Eighteen: For Better, for Worse

Chapter Nineteen: Dearly Beloved

Chapter Twenty: It’s Me or a Dog

Chapter Twenty-One: Something Blue

Chapter Twenty-Two: White Wedding

Long, irregular hours; occasional risk of injury; often smelly and dirty. Job satisfaction guaranteed.

This is the life Maz Harwood signed up to when she became a vet, and she has never regretted it. She now has a beautiful baby boy, George, and she will be marrying fellow vet, Alex Fox-Gifford, at Christmas.

But recently things have become difficult. Because between arranging the wedding, performing life-saving animal surgery, and taking care of George, there hasn't been much time left for poor Alex.

So Maz decides to take things into her own hands – with terrible consequences for all concerned.

As Christmas draws near, Maz realises that if they're ever going to make it up the aisle, she's going to have to prove to Alex that she will always love him, no matter what.

Cathy Woodman was a small animal vet before turning to writing fiction. She won the Harry Bowling First Novel Award in 2002 and is a member of the Romantic Novelists’ Association. She is also a lecturer in Animal Management at a local college.

It’s a Vet’s Life

is the fourth book set in the fictional market town of Talyton St George in East Devon, where Cathy lived as a child. Cathy now lives with her husband, two children, two ponies, three exuberant Border terriers and a cat in a village near Winchester, Hampshire.

Other books by Cathy Woodman

Trust Me, I’m a Vet

Must Be Love

The Sweetest Thing

To Jess, with love

Horses for Courses

‘MAZ? MAZ, WE’RE

in business.’ The figure of Alex, my fiancé, appears in the doorway, bright sunlight glancing past him, casting his shadow across the stone floor inside the Barn. ‘Hurry,’ he goes on.

‘Sh,’ I whisper from the sofa, as George stirs in my arms at the sound of his father’s voice. ‘Not so loud. He’s only just gone off.’ I press my lips to the top of George’s head. He doesn’t seem to have got the hang of napping even after twenty-one months. In fact, I reckon the gene for sleeping, if there is such a thing, has bypassed him entirely.

‘But, Maz, it’s on its way.’ Alex lowers his voice as he moves closer.

‘That’s what you said before.’ I smile. Alex has been on tenterhooks for at least a week. ‘Are you sure this isn’t another false alarm?’

‘Absolutely. One hundred per cent.’ Alex’s fiercely blue eyes flash with impatience. His short, dark hair is flecked with grey, which he claims is a consequence of being with me, rather than his advancing years,

something

I enjoy teasing him about since I’m younger than him. At the moment, it’s also adorned with curls of wood shavings.

We’ve been together for three years, through both happy and testing times, and he’s still as attractive as ever, dressed today in a check shirt and snug-fitting jeans that hug the contours of his lean, yet muscular thighs. Almost every day I thank my lucky stars that I accepted my best friend Emma’s request to look after her practice to give her a break. If I’d turned down that opportunity to come and work in Talyton St George, I’d probably still be working as a city vet somewhere in London, and Alex and I would never have met.

‘Come on, or you’ll miss it, and it isn’t something you see every day,’ Alex says. ‘Bring George with you.’

I wake our son with the slightest touch on one cheek. He lifts his head, blinks and stares at me, frowning.

‘Hiya, are you coming outside to help your daddy?’

‘No,’ George mumbles.

‘I think you mean yes,’ I say.

‘No.’ George’s mouth curves into a dribbly smile. His hair, dark and glossy like a flat-coated retriever’s, sticks up damp from his forehead, and tiny beads of sweat bubble up across the bridge of his nose.

Picking him up, I pad across the cool floor and slip into a pair of flower-power clogs which are lying where I left them, behind the front door and alongside George’s toys and a rack of magazines, ranging from

Horse & Hound

and

Veterinary Times

to

Mother & Baby

. I’m not sure why we have them – we don’t have much opportunity to sit down and read.

‘Alex, wait for us,’ I call, but he’s already striding ahead and disappearing into one of the stables in the double-storey block to the left-hand side of the yard.

The

ground floor consists of a row of loose boxes, while steps lead up to the old hayloft that’s now the Talyton Manor Vets’ office and surgery.

Opposite the Barn where we live, there is an assortment of vehicles parked on the gravel: four-by-fours, an ancient Bentley and a horsebox in purple livery. Beyond these is the rear of the Manor House where Alex’s parents live with their dogs, and a Shetland pony which is often to be found in the drawing room. That makes it sound incredibly grand, but the place is falling down around their ears. Its windows are cracked, its roof tiles slipping and its walls crumbling. If it were an animal, the RSPCA would have been in to rescue it by now.

To the right-hand side of the yard, there are green fields, subdivided into paddocks with electric tape, where several horses are grazing, flicking their ears and swishing their tails at the flies which are out in force, strangely energised by the June heat.

I reach the stable and look over the half door. Alex stands at the head of his beautiful chestnut mare, holding on to her by a rope attached to a leather head collar with brass buckles, as she lies on rubber matting scattered with fresh shavings.

Gradually, the scent of horse and disinfectant replaces the sweet smell of baby bubblebath and fabric conditioner in my nostrils. The mare’s flanks grow dark with sweat and Alex’s forehead shines. George seems to be getting hotter too – and heavier. I shift him onto one hip.

‘No!’ George wriggles to get down, as the mare strains and groans, taking me back to a painful and not-so-distant past when the River Taly burst its banks, and I went into labour prematurely with George. I

shudder

even now to think of the icy black water, the ever-diminishing patch of ground on which I stood, and the waves of pain that racked my body. I remember the relief I felt when Alex turned up, emerging from the darkness to rescue me, and the panic when the baby was born all blotchy and lifeless, and I thought we’d lost him. I can also recall the angst I went through, wondering if I could ever bond with a child. I can smile about it now. I never intended to be a mother, let alone endure a water birth like that one.

‘Shall we leave you to it, Alex?’ I don’t want George’s toddler noises to upset Liberty and stop her in the middle of giving birth. I have every sympathy with what she’s going through.

‘Stay,’ Alex says. ‘You and George missed the last one.’

This is Liberty’s second foal – Hero was born last May. Alex’s mare was a promising showjumper until an attack of colic and the ensuing emergency surgery to save her life brought her career to a premature end, along with Alex’s ambition to be selected for the British Showjumping team.

‘I hope you’re not planning on brainwashing our son into following in our footsteps. Aren’t three vets in the family enough?’ I say lightly.

‘I’m thinking of the future of the practice.’ Alex grins.

‘Don’t you mean practices?’ Alex runs Talyton Manor Vets, a farm animal practice with a few small animal clients, alongside his father, while Emma and I are partners in Otter House. ‘Anyway, I thought Seb was being groomed to take over from you when you’re too old and decrepit to do the James Herriot thing any more.’

‘It’s a little more sophisticated than that nowadays.’

‘You still spend a lot of time with your arm inside a cow,’ I point out. ‘Your offspring might not appreciate the outdoor lifestyle.’ Alex has two children, other than George, from a previous relationship, a failed marriage. Seb is only five. Lucie is almost nine, and I would guess that of the three, she is the most likely to follow in her father’s footsteps. ‘How’s she doing?’

‘Liberty’s doing fine. Aren’t you, my girl?’ Alex squats on his haunches beside her, his eyes on her tail end where the water bag appears and bursts, spilling fluid across the floor, before Liberty strains once, twice and three times more. ‘Ah, I can see feet. It’s on its way.’

‘Is everything all right?’ I ask, anxious for both the mare and foal, and Alex, when nothing more happens for a while.

‘She’s resting.’ Alex checks his watch. ‘It’s quite normal.’ However, he moves in closer, examining the foal’s feet which are clearly visible now. I see Alex’s body tense as the mare strains again.

Something is wrong.

Alex swears out loud, making George jump and grab a handful of my blouse to steady himself.

My mind races ahead. It’s too late to get Liberty to the nearest equine hospital with surgical facilities, and there’s no way we can use the operating theatres in either practice because they’re designed for small animals, not horses. The biggest patient we’ve had in for surgery is a Great Dane and we had to extend the table with a trolley for him.

‘It’s coming backwards.’ Alex’s voice is flat and matter-of-fact.

‘Shall I run and fetch your father?’

‘It’s too late for that. Hang on to her for me.’

I wonder what to do with George and decide to hold on to him. If there isn’t time to fetch help, there isn’t time to go and grab George’s buggy. I open the stable door and take hold of Liberty’s head collar, hanging on while George tries to lean down and touch her ears, and Alex tips most of a bottle of obstetrical lubricant over his hands and tries to work out how to deliver the foal.

‘I wish it was coming any way other than this. It needs to come out right now.’

I know what he means. I can vaguely recall the notes I wrote at vet school about managing a foaling. When the foal is coming out backwards, hind feet first, the umbilical cord gets squeezed against the mare’s pelvis, cutting the oxygen supply and triggering the foal’s first breath. If it breathes with its head inside its mother’s womb, it will take in fluid and drown.

‘Is it the right way up?’ I ask.

‘It is,’ Alex confirms.

That’s a start, I think, as Alex takes hold of the foal’s back legs and hauls at it with all his weight behind him, his feet pressed against Liberty’s buttocks, the muscles in his arms taut and corded, his skin glistening with sweat and effort. It looks brutal, but there is no other way.