It's Bigger Than Hip Hop: The Rise of the Post-Hip-Hop Generation (23 page)

Read It's Bigger Than Hip Hop: The Rise of the Post-Hip-Hop Generation Online

Authors: M.K. Asante Jr

M.K.A.: Do you have a message to the youth, perhaps, that you’d like to express?

Dead Prez: If I had to deliver a message to the youth I’d say to keep your eyes open and your fist clenched. I’d say they can try to kill the messenger but they can’t kill the message, they can try to jail the revolutionary but not the revolution.

M.K.A.: Peace.

Dead Prez: Peace.

Although the racist, hostile, and violent attitudes police officers display in cities across America present a real problem, the new generation mustn’t be shortsighted in analyzing and solving this age-old conflict. Just as we cannot blame the teachers who are put in crumbling, overcrowded schools for the education problem or the soldiers on the ground in Iraq for the war, we must be committed to working our way up the ladder of power. It is there—among the decision makers—that the problems that plague all of us are preserved and maintained. Despite the anger that we may feel toward police, it is not guns that will save our collective lives, for they never have and never will. Instead, it is organizing in such a way to attack the injustice at its root and save the lives of our unborn children and grandchildren. Most important, it is up to us to imagine a new system—a system not rooted in the past of America’s slavery days, but in the freedom of tomorrow.

*

Fight the Power; Fuck the Police; Free the Prisoners; Free the People; For the People; Feed the People.

The only thing worse than fighting with your allies

is fighting without them.—

TRADITIONAL SAYING

Take sides. Neutrality helps the oppressor,

never the victim. Silence encourages the tormentor,

never the tormented.—

ELIE WIESEL

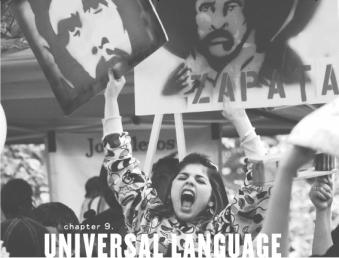

“El

pueblo unido jamás será vencido

.

El pueblo unido jamás será vencido,”

I soul-shouted from the center of my heart as I marched through the haze of downtown L.A. with a half million brown brothers and sisters behind me. Another half million in front. Across the United States—in Houston, Philadelphia, Lexington, Boston, New York, Washington, D.C., Las Vegas, Miami, Chicago, San Francisco, Atlanta, Denver, Phoenix, New Orleans, Milwaukee, and everywhere in between—similar spirits

were stomping, sweating, and singing songs of freedom and resistance—songs arranged with courage, inspired by revolution, organized peacefully, and played loudly before the whole wide world.

Unify with others who have also been denied

their existence to discover the magnitude of

our collective resistance

.—

WELFARE POETS, “IN THE SHADOW OF DEATH

,”

RHYMES FOR TREASON

I would have marched that day, May 1, 2006, even if I wasn’t in production on

Super Imigrante

, a documentary film about Latino immigration/migration in America. Even if I hadn’t spent months in the homes of undocumented citizens and in predominantly Latino schools, recording their struggles. Even if I couldn’t speak or understand Spanish, which, for the most part, I couldn’t. In fact, that day—which came to be known as “a day without immigrants”—was the first time in my life that I’d said more than

“hola”

in Spanish.

My voice grew louder as my ebony fist, in unison with all of the other fists, thrust toward the heavens.

“El pueblo unido, jamás será vencido!”

The massive demonstrations were sparked by the racist attitudes and policies aimed primarily at Latino immigrants. Specifically, the Border Protection, Antiterrorism, and Illegal Immigration Control Act (HR 4437), a bill introduced by House Judiciary Committee Chairman James Sensenbrenner (R-WI). Rather than provide a comprehensive, rational, and effective approach to immigration issues, Sensenbrenner’s bill vilified immigrants. Among its many provision, HR 4437 would make it extremely difficult for

legal

immigrants to become U.S. citizens; would make it a felony to aid or transport any undocumented worker including family members and relatives; would

make all immigrant workers subject not only to deportation but also imprisonment; and would drastically disrupt the U.S. economy by instituting an overly broad and retroactive employment verification system without creating the legal channels for workers to acquire verification.

“El pueblo unido, jamás será vencido!”

My comrade and codirector, Abraham, whose dad had left Mexico, his country of birth, in the tattered trunk of a battered Buick, knew that I didn’t speak or understand Spanish, his native language.

“Yo, want me to tell you what that means?” he asked me as we filmed the shimmering sea of tan faces that transformed L.A.’s smoggy landscape into a cloudless one; both the vision and the focus was clear.

“I already know what it means,” I told him as our wide eyes met and our heavy heads nodded to the invisible rhythm of common understanding.

At that moment, he knew that

I knew without knowing

.

I didn’t know the linguistic translation into English, but I knew the emotional translation. I didn’t know that the lines I sang were from a song written by Chilean composer Sergio Ortega, but I knew that they were written for those of us who were, at that moment, writing history with the boiling ink that surged through our bodies. I knew that human beings weren’t “illegal.” That, actually, employers who exploit vulnerable workers are the criminals. That Chicano children—like African, Native American, Asian children, et cetera—need to learn about their history and their people’s contribution to the world. That wrenching apart families is wrong. And that searching for a better life, just as the heroic, green card-less immigrant Superman did when he fled Krypton, is a human right.

“El pueblo unido, jamás será vencido!”

When the rain falls

It don’t fall on one man’s house

.—

LAURYN HILL, “SO MUCH THINGS TO SAY

,”

MTV UNPLUGGED

When Mexico welcomed Africans who’d escaped the shackles of slavery in the nineteenth century, they were doing the same thing I was doing: recognizing the connectedness of struggles against oppression and domination. Historically, it has been the failure to recognize this connectedness, combined with strategic campaigns by those in power to ensure disunity, that have kept the oppressed

oppressed

. As raptivist Immortal Technique explains:

Black and Latino people don’t realize that America can’t exist without separating them from their identities, because if we had some sense of who we really are, there’s no way in hell we’d allow this country to push its genocidal consensus on our homelands

.

Blacks and Latinos in America are both suffering under the same oppressive system of structural racism and domination. As Latina activist Elizabeth Martinez points out in her “Open Letter to African-American Sisters and Brothers”: “We’re both being screwed, so let’s get together!”

It is because we are “both being screwed” that we need to resist those people who seek to divide. Those poor Blacks and whites who scream that “the Mexicans are taking our jobs!” “No,” we must explain to them, “rich white men are giving away your jobs to workers who they can not only pay less, but also workers who are more vulnerable. Workers whom they feel they don’t have to pay at all. Workers who can be threatened with deportation.”

The river of resistance to oppression flows far beyond African-American or Mexican struggles. The resistance is, indeed, a river. And that river, although it may pass through many countries that claim it as their own, is just one river. This hit me, on a spiritual level, when a Salvadoran friend of mine called me from Malcolm X Park in Chicago where thousands of people from different neighborhoods and ethnicities had formed a human chain as a symbol of their togetherness. The fact that this chain of solidarity was happening in Malcolm X Park couldn’t be more fitting. For it was Malcolm who knew, toward the end of his life, that the fundamental problem is not between Blacks, whites, browns, yellows, reds, or any other racial category, but rather, between the oppressed and those who do the oppressing, the exploited and those who do the exploiting—regardless of skin color.

Malcolm realized that the only way to fight oppression is to unite with people who share the same spirit of resistance against inhumanity and injustice—and those spirits may, and in fact should, have different colors, genders, religions, et cetera. We may not always agree on the fine points, but those who are fighting against oppression must

unite. Malcolm, for example, just before his death, visited Dr. King in Selma. Although for years they’d publicly disagreed on many issues, Malcolm offered his hand in friendship to Dr. King, explaining, “We may differ, Martin King, on tactics, we may differ on philosophy, we may differ on many things, but you are black, and I am black, and let’s not forget that, and let’s stand together on that basis!” This fraternal act had a contagious effect as Dr. King, just weeks after he won the Nobel Prize, went to Newark, New Jersey, to see Amiri Baraka (then LeRoi Jones) to extend the same statement of brotherhood that Malcolm made to him. They believed that being Black was enough to establish unity. Today, we must take that brotherhood and make sure it is motherhood, sisterhood, and simply hood. We must unite not simply around color, for we know now that oppression comes in many colors, and we must simply be against it in all of its colors.

What unites me with my Latino/a brothers and sisters, now, again, is the struggle—not for civil rights but to the higher level of human rights. It is important that we never fall into the trap of demoting human rights issues to civil rights struggles. When we do that, we limit the involvement and influence that the international community can have. Let us never forget that the Latino struggle in the United States is not one that is solely under the jurisdiction of the Untied States, but it is an international issue of human rights. For when we elevate our causes to the level of human rights, the world hears us—as they heard Paul Robeson’s deep baritone. “You are our children,” he told us, “but the peoples of the whole world rightly claim you, too. They have seen your faces, and the faces of those who hate you, and they are on your side.”

We see this idea of solidarity and unity in the late Tupac’s art gallery of a tattooed chest. Directly in the center is a charcoal-colored AK-47 with the words “50 Niggaz” hovering above it. The idea behind

the tat is that if “niggaz” in all fifty states united, we could bring about radical change. I say it’s time to take Tupac’s idea to that next level: 50 Nationz.

There’s a button displayed in the window of Red Emma’s, a collectively owned radical bookstore in Baltimore named after Lithuanian-American revolutionary Emma Goldman, that reads:

I AM PALESTINIAN

. And in that one button, we can see thousands more that have yet to be made and worn: I am a Zapatista. I am Tibetan. I am Bosnian. I am South African. I am African-American. I am Chicano. I am Indian. I am Iraqi. I am Oppressed. My future is in progress.

If we want to fully understand what is happening in Baghdad, we must understand what’s happening in Soweto and North Philadelphia, et cetera. They are, like the rivers, not just connected, but one. Malcolm concludes:

You cannot understand what is going on in Mississippi if you don’t understand what is going on in the Congo, and you cannot really be interested in what’s going on in Mississippi if you are not also interested in what’s going on in the Congo. They’re both the same. The same interests are at stake. The same ideas are drawn up. The same schemes are at work in the Congo that are at work in Mississippi. The same stake—no difference whatsoever

.